After a year and a half of stalling, the Boston Police Department finally replied last month that it has no guidelines for cell phone data retention or sharing, and that virtually all operational documents around cell phone surveillance must be withheld from public release.

Like many of the police departments around the country we intend to survey as part of “The Spy in Your Pocket,”, the BPD has released precious few details about its cell phone surveillance tactics or the steps its officers take to balance investigative priorities with privacy concerns.

In August 2012, I asked the BPD for documents regarding cell phone surveillance. It was one of the first Freedom of Information requests I ever submitted, the language pulled from similar requests submitted by ACLU affiliates nationwide.

The BPD’s public records team acknowledged my request in September 2012, but it took more than a year for police officials to issue any further response.

In October 2013, Boston police brushed off the request: “In response to your request, a search of records was performed and the Department does not have any documents in its possession, custody or control that are responsive to your request.”

Given the breadth of my request — which encompassed everything from procedures for obtaining cell phone data to to invoices from carriers for user queries — it seemed incredibly unlikely that a department of BPD’s size would have no documentation whatsoever.

After another six months, records staff did manage to track down one training bulletin from the Boston Police Academy.

The three-page brief dated March 2013 reviews Massachusetts case law regarding cell phone searches following arrest.

The department’s response to the remainder of the request is more illuminating.

A “comprehensive search” once again failed to unearth any documents detailing how long detectives may hold onto location data gleaned from cell phones, or which agencies exchange data with the BPD.

But, the BPD changed its stance on several other fronts in the May 2014 response - namely by claiming law enforcement privileges around particular documents. When it comes to operational guidelines for using cell phones to map social networks or identify all individuals at a given place, for instance, as well as invoices that detail the cost of obtaining such details from mobile carriers, Boston police insist that releasing such documents would “prejudice the possibility of effective law enforcement.”

That combination of “we don’t have it” with “you can’t have it” is precisely what motivated MuckRock to investigate cell phone surveillance practices by police nationwide.

Whether obtained from carriers, or via devices like Stingrays, cell phone data contains sensitive information about the movements, communications, and activities of individuals. We’re committed to uncovering just how law enforcement obtain this data, how they protect, share, and store it, and at what cost to taxpayers.

As with our investigations of drones and license plate readers, your support is critical to launching “The Spy in Your Pocket.” By subscribing for as little as $5 per month, you can play a part in making law enforcement more transparent and accountable.

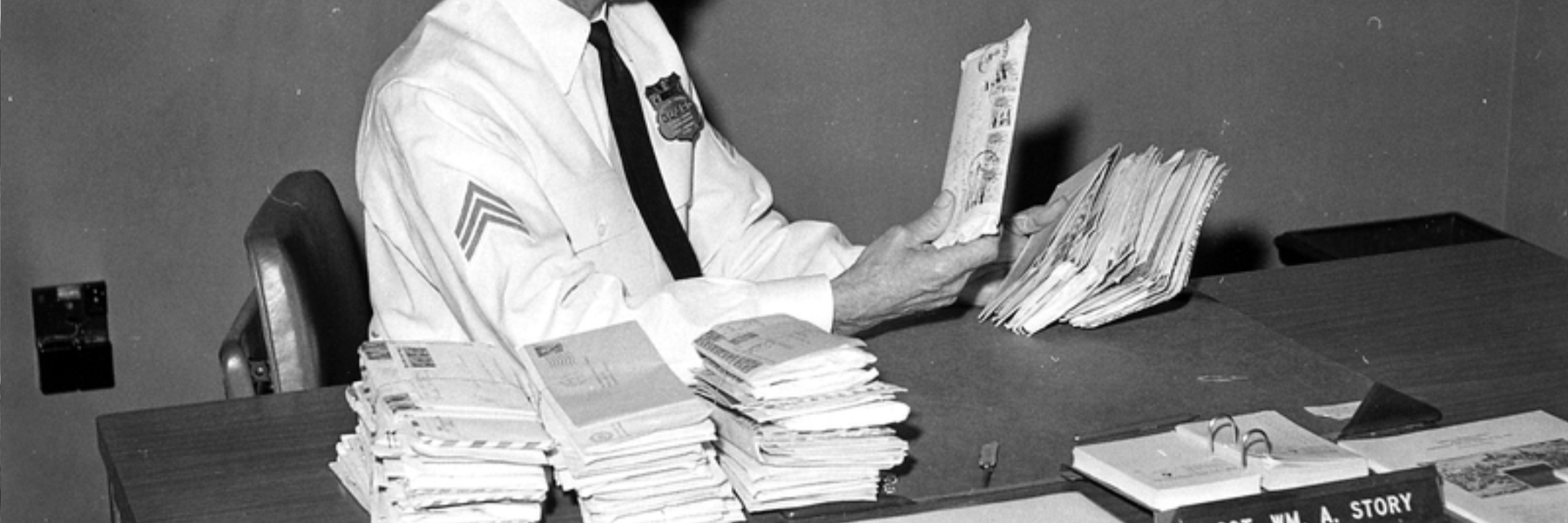

Image via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0