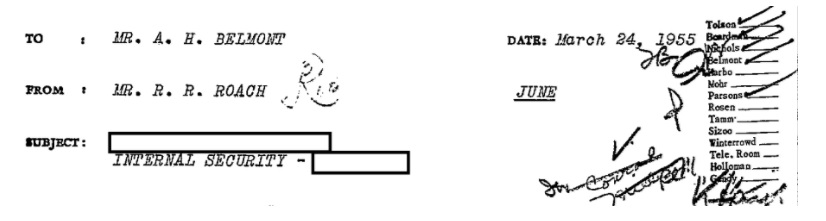

A heavily redacted section of the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s file on Technical Security Surveys shows just how easy it was for embassies to tap government phones in the mid-’50s. After discovering that the French were listening in on the White House, the FBI to uncovered dozens of phone lines belonging to the governments of American allies that were vulnerable to Communist governments. While securing these lines, a phone tap on the Soviet United Nations delegation had to be pulled - leaving the Bureau with no choice but to go through the Italian embassy.

Although heavily (and arguably excessively) redacted under FOIA exemptions b(1), b(6), b(7)c and b(7)d, and exempted from declassification under 25X1 to protect sources and/or methods “currently in use, available for use, or under development,” several pieces of redacted information are discoverable by compiling information from different parts of the file.

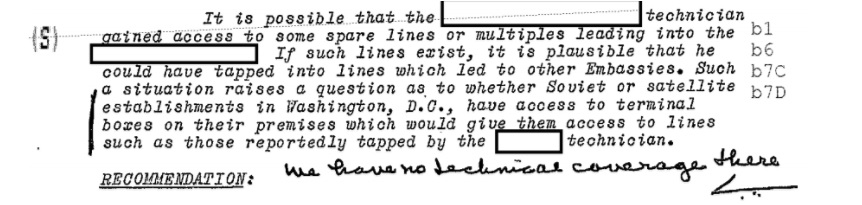

The earliest memo in the sequence of documents reveals only that someone associated with an embassy may have “gained access to some spare lines or multiple” lines. If so, the file argued, an unidentified technician might have gained access to lines leading to other Embassies. This also raised the question of whether the Soviets had achieved a similar feat.

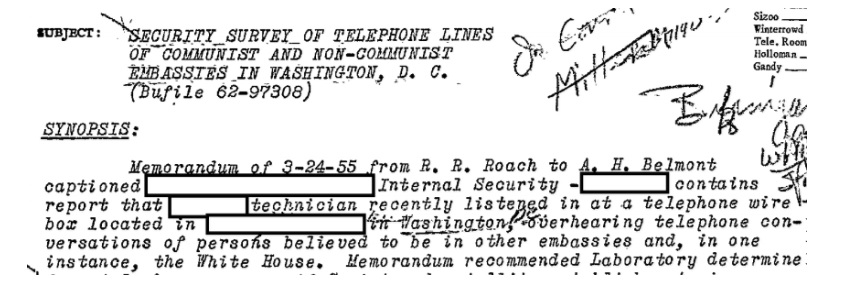

A subsequent entry in the file reveals slightly more, showing that the technician had used a telephone wire box to listen in on phone calls believed to come from other embassies as well as the White House. As a result, the Bureau decided to look into the matter more closely.

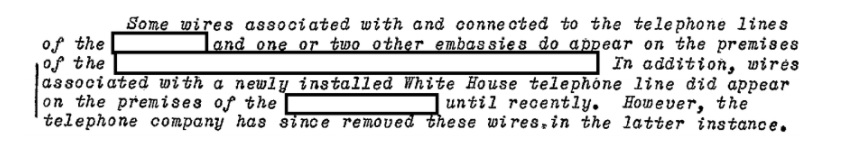

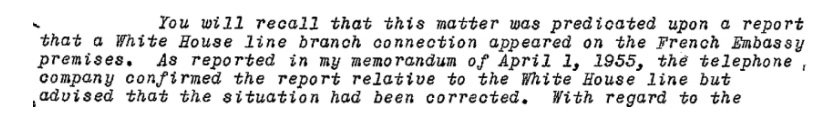

After an initial review, the Bureau learned that several wires did cross between various embassies. The Bureau also learned that access to a new White House phone line had recently appeared on an unidentified location.

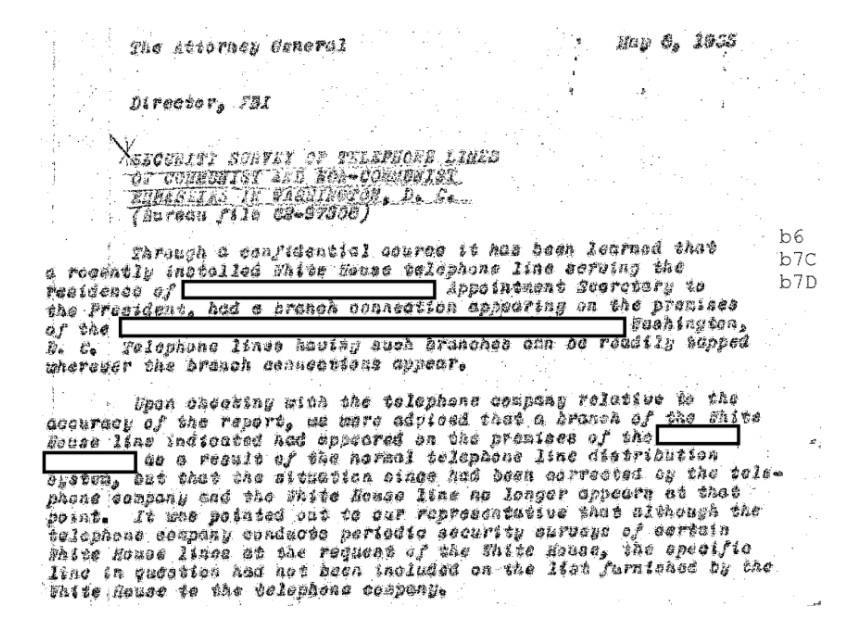

A subsequent memo between FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and the Attorney General identified the White House phone line as belonging to the Appointment Secretary to the President. According to the memo, a branch of the phone line appeared on the unidentified premises, and “such branches can be readily tapped wherever the branch connections appear.” By the time the Attorney General was informed, this particular issue had reportedly been fixed.

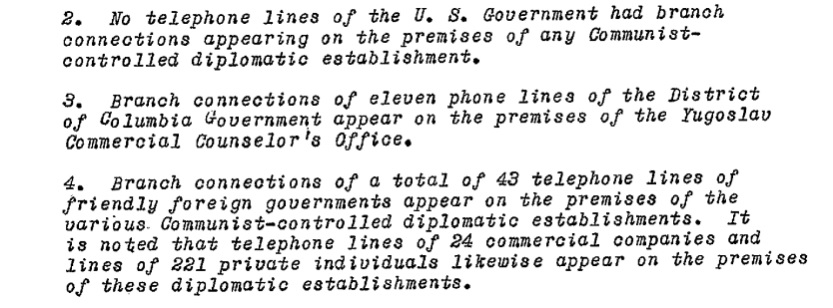

The memo goes on to note that no evidence had been found that the Soviets had access to U.S. government phone lines, though a Yugoslavian office had access to at least 11 lines belonging to the government of the District of Columbia. A follow-up memo notes that the Bureau was continuing to look, both in Washington D.C. and in New York City.

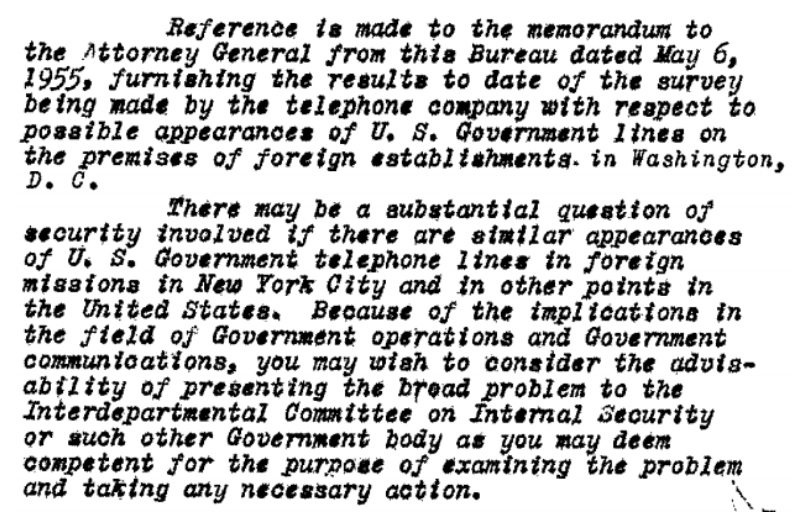

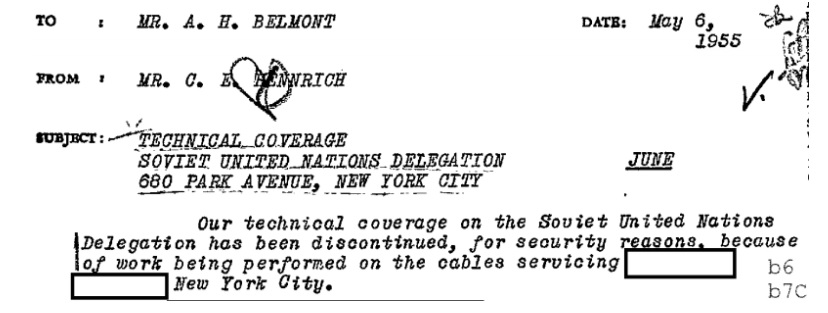

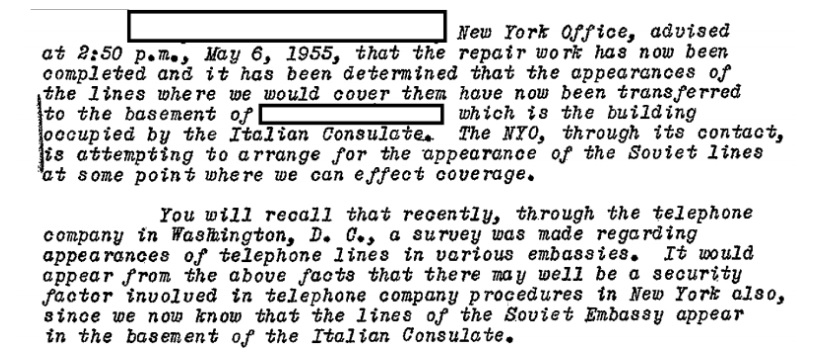

Checking for these vulnerabilities, and taking corrective measures, appears to have created new problems for the FBI’s own surveillance of foreign consulates. According to a May 6th, 1955 memo, the work on cables in New York City forced the Bureau to terminate their “technical coverage on the Soviet United Nations Delegation … for security reasons.”

As a result, the lines had been transferred to the basement of the building housing the Italian Consulate. As a result, the Bureau’s New York Office was “attempting to arrange for the appearance of the Soviet lines to some point where [the FBI] can effect coverage.” The memo also expressed concern about “a security factor involved in telephone company procedures” due to the Soviet lines appearing in the basement of the Italian consulate.

A subsequent memo identifies the Embassy where the White House phone lines, and phone lines of other embassies, had appeared as the French Embassy.

As the scope of the search expanded, the FBI and the phone company learned more about the situation. While no U.S. government phone lines had appeared on Communist controlled facilities and 11 phone lines belonging to D.C. government appeared on the premises of the Yugoslavian Commercial Counselor’s Office, the phones of American allies had worse luck. According to a May 1955 memo, there were 43 phone lines belonging to “friendly foreign governments” appearing “on the premises of the various Communist-controlled diplomatic establishments.” These communist facilities also had access to the phone lines of 24 commercial companies and 221 individuals.

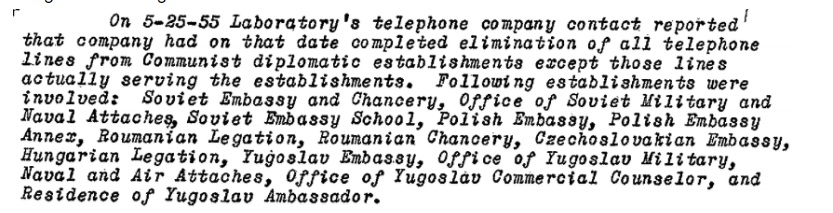

These “Communist-controlled diplomatic facilities” appear to have included the Soviet Embassy and Soviet military offices, the Polish Embassy, as well as Romanian, Czechoslovakian Hungarian and Yugoslavian facilities.

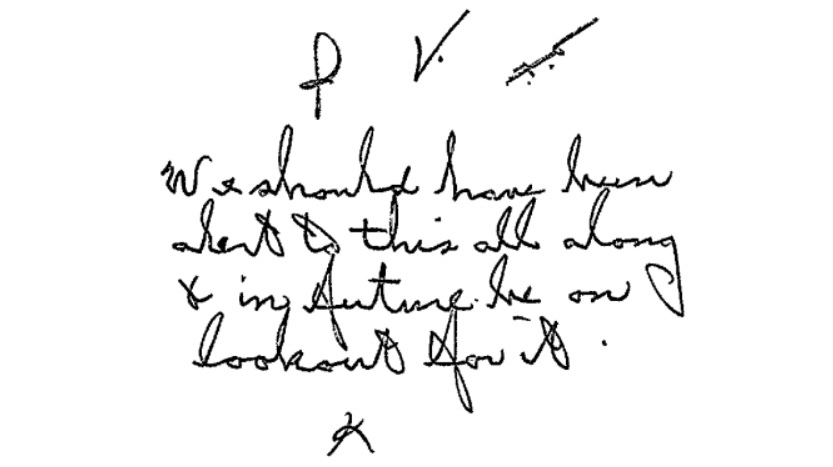

Access to these lines was terminated, though one handwritten note in the FBI file points out that the risk should have already been addressed.

Having reviewed Communist and Soviet offices, the phone company moved on to looking for instances of government phone lines appearing on the property of 71 different friendly foreign governments.

As a result of this survey “of 71 non-Communist diplomatic establishments,” 13 phone lines belonging to the U.S. Government and three belonging to the D.C. Government were found on the premises of six unidentified facilities.

Due to the expense that would be involved in taking corrective measures, and the perceived unimportance of the matter, the phone company decided that it wouldn’t take corrective action - unless it was specifically requested to do so.

By the end of August, however, the phone company appeared to have changed its mind on this question and had removed eight of the 16 phone lines identified from foreign soil.

Within two weeks, the phone company had finished removing the other eight phone lines.

A June 1955 memo from Deputy Attorney General Rogers to the FBI Director suggests contacting the General Services Administration, “which furnishes the buildings occupied by most Government agencies [and] also has the responsibility for furnishing adequate telephone communications and for the security of such telephone lines.”

Hoover’s response, while included in the file, has faded into illegibility.

A later letter to Hoover shows that the GSA became involved as a result of Hoover referring the matter to the Interdepartmental Committee on Internal Security, which in turn contacted the GSA in late September 1955 to learn how far the problem went beyond Washington, D.C. and what issues affected Government offices that the GSA didn’t have responsibility for.

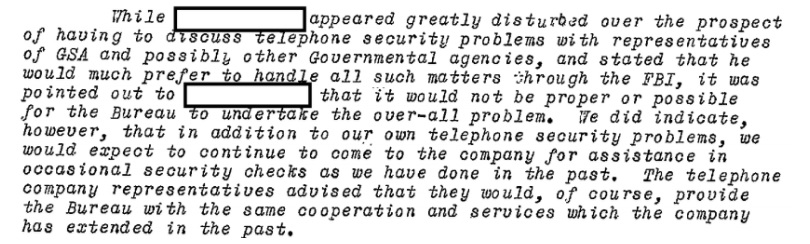

The prospect of briefing the GSA or other government agencies resulted in one of the Bureau’s contacts at the phone company to appear “greatly disturbed.” The Bureau, however, declined to “undertake the over-all [sic] problem,” noting that “it would not proper or possible” to do so. The Bureau did expect the phone company to continue to provide assistance to the FBI on select matters in the future.

The phone company’s reluctance to share any information with various government offices is hardly surprising, in light of their refusal to share similar information with the White House the year before.

You can read the relevant section of the FBI file below, or the rest of the release on the FBI’s Technical Security Surveys on the request page.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons