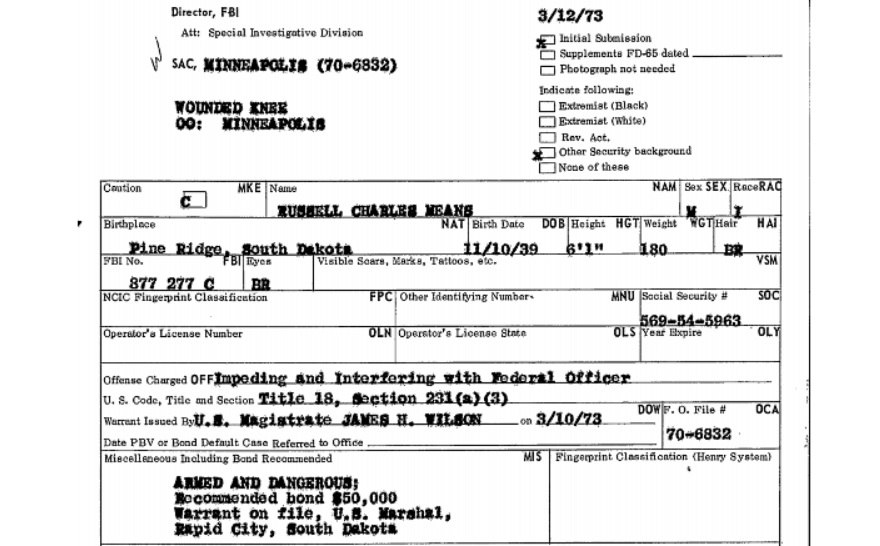

Russell Means was a seminal figure in Indigenous politics for decades, rising to the rank of National Director of the American Indian Movement in 1970. His 178 page FBI file, however, only includes records regarding one incident Means was involved in - the occupation of Wounded Knee, a months-long standoff between AIM activists carrying small arms, and local and federal law enforcement packing 133,000 rounds of ammunition, armored personnel carriers, and .50 caliber machine guns.

In 1973, the year of the armed Wounded Knee takeover, the predominantly Oglala Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation was headed by the Tribal Chairman Richard Wilson. Wilson was infamously corrupt, cutting the Tribal Council down from 18 members to just five, and installing friends and family in positions of power. Furthermore, Wilson tended to favor “Americanized Sioux” rather than the large numbers of traditional Lakota who lived on the outskirts of the Reservation, and went against their wishes in the case the Lakota had brought against the U.S. government in an attempt to reclaim the sacred Black Hills, favoring a cash settlement instead of land returned. As protests increased due to his heavy involvement with the U.S. government and his reliance on the BIA, he created his own private police force, the Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs). Political violence soon began to spread out of control on the Reservation, something which the US government overlooked for years.

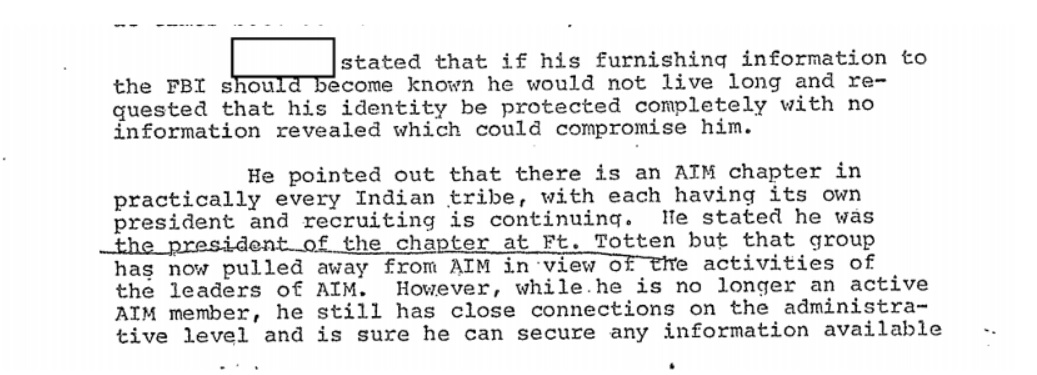

By early 1973, AIM chapters were springing up all over the Reservation after Wilson had harshly spoken out against the AIM occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affair’s (BIA) DC headquarters. Coupled with the vicious poverty at Pine Ridge, and years of broken treaties by the U.S. government, and it is hardly surprising that so many turned to the American Indian Movement. As one source told the Bureau “there is an AIM chapter in nearly every Indian tribe.”

While the FBI had certainly been keeping tabs on the AIM prior to 1973, their interest skyrocketed when over 200 Lakota and outside AIM members, led by Means, Dennis Banks, Clyde Bellecourt and other AIM leadership, rolled out from Calico, South Dakota, to Wounded Knee, South Dakota on February 27th 1973 in a long convoy. Wounded Knee is an especially symbolic place, the site of a massacre of 300 Sioux women and children in 1890 by U.S. cavalry.

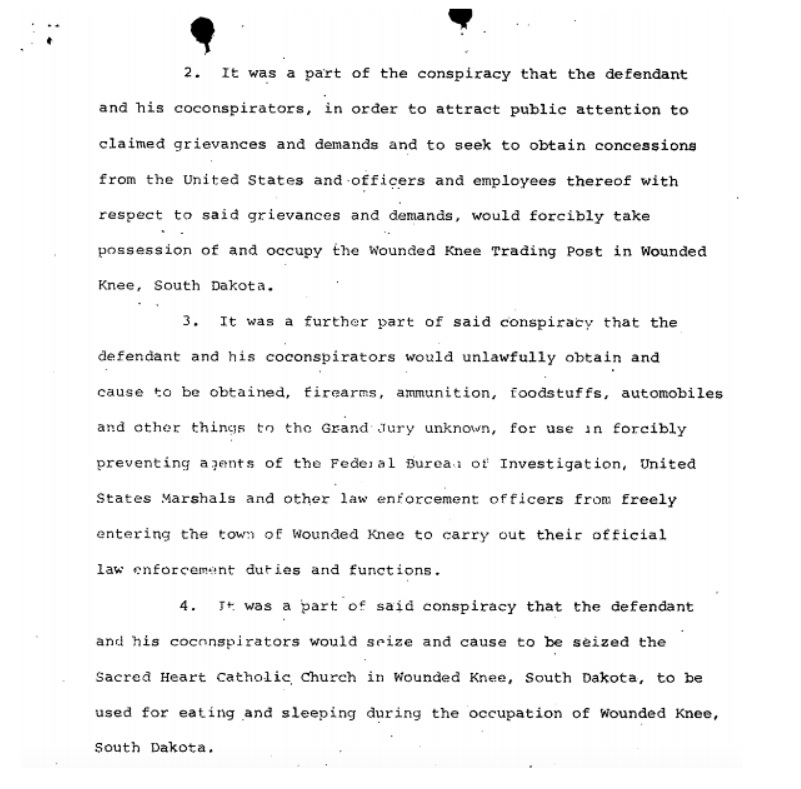

The Grand Jury charges Means was brought up on offer some insight into the beginnings of the armed takeover. Weapons were carried in select cars, and mostly consisted of older .308 and .22 caliber rifles, shotguns, pistols, molotov cocktails, and a few machine guns. When arriving, the first thing Means did was occupy the Wounded Knee Trading Post, ransacking its food and weapon supplies. On the next day, the 28th, Means ordered the burning of motor vehicles belonging to the Trading Post, and erected roadblocks, which would serve as armed checkpoints for the AIM during the struggle.

With federal law enforcement closing in around them, Means and other American Indian Movement leadership ordered trenches and bunkers dug, and a local Catholic Church seized in order to have a place to eat, sleep, and launch patrols. Over the course of the next three months there were frequent episodes of firefights, resulting in the deaths of two AIM members, two FBI agents, and the paralysis of a U.S. Marshal. At least 13 members of the AIM were wounded in the struggle. With the entrenchments that AIM had dug, their constant scouting, and their steady procurement of weapons, the federal forces found it very challenging to uproot the revolutionaries, and often left it up to Wilson and the GOONs to lead the attacks on AIM.

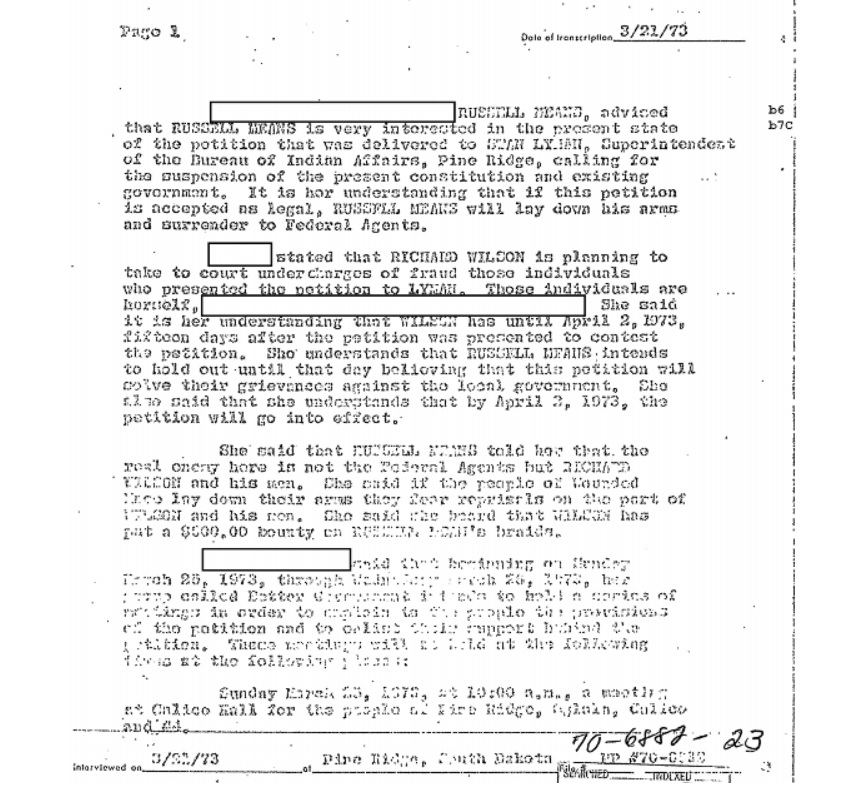

Indeed, as one source advised the FBI, “Russell Means told her that the real enemy is Richard Wilson. She said if the people of Wounded Knee lay down their arms, they fear reprisals from Wilson and his son. She says she had heard that Wilson had put a $500 bounty on Russell Means’s braids.”

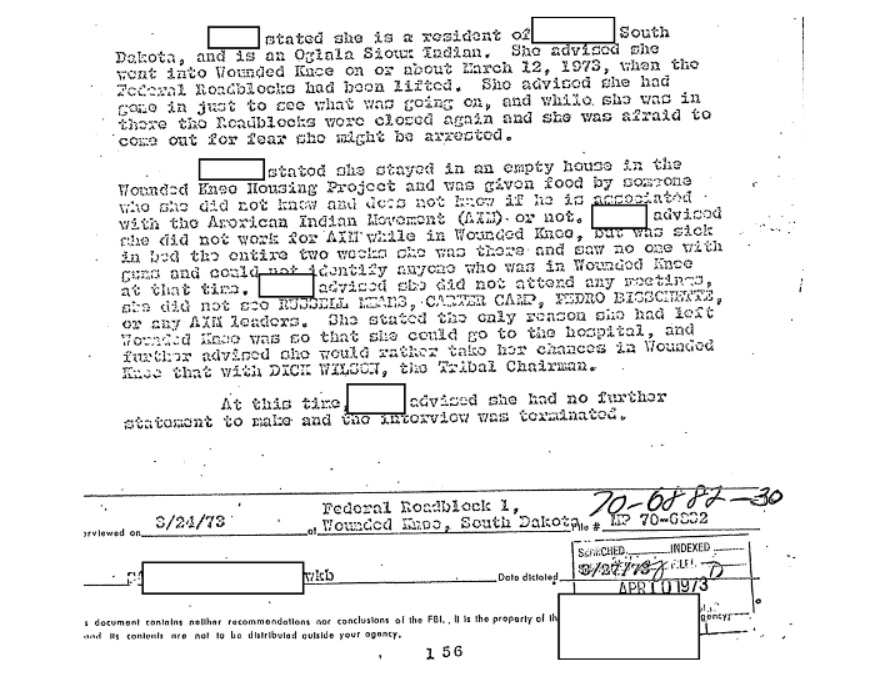

In the three years after the Wounded Knee occupation, and with the FBI’s documented awareness of the problem, over 50 political enemies of Wilson were murdered out of a total Reservation population of about 20,000. Another non-AIM source told the Bureau she would rather take her chances in Wounded Knee than with Richard Wilson.

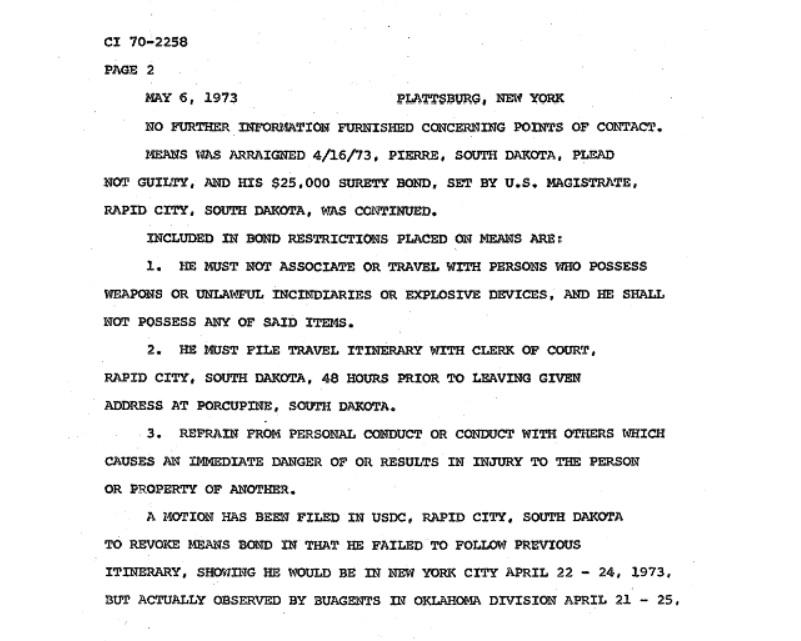

By March the numbers within Wounded Knee had reached at least 300 or 400. On the 24th the Bureau spoke to a source who told them Means had Wounded Knee’s population’s “100% support” and that he had forbidden drugs and alcohol. Just days later on April 5th, Means was arrested by the BIA when he attempted to slip out of Wounded Knee. Means was given a $25,000 bond after his arraignment in Pierre, the state capitol. On April 10th, Means was let out on bond, beginning a furious period of investigation by the FBI. As part of Means’s bond agreement, he had to submit an itinerary to the U.S. district court in Rapid City, South Dakota whenever he left his home in Porcupine, South Dakota. If he was found to have violated the itinerary, his bond would be revoked and he would be reincarcerated.

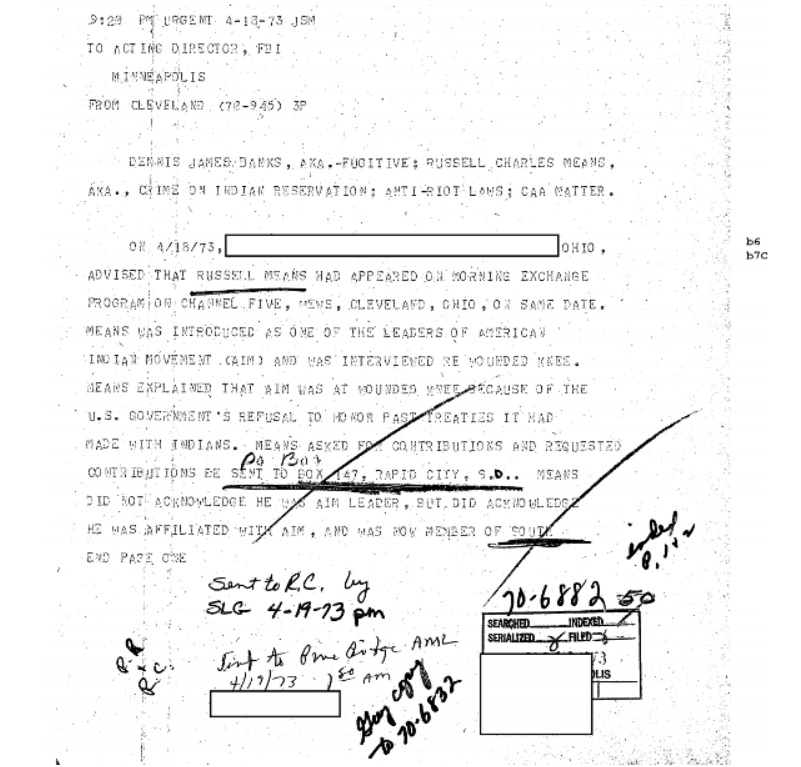

Means was not only an invaluable leader in the AIM’s armed struggle against Richard Wilson and the US government, but was a masterful fundraiser and orator. To this end, he began to travel around the country to drum up support for the AIM - and the FBI followed right on his tail, hoping to catch Means doing something they could arrest him on. This surveillance program involved the highest levels of the Bureau, including the then-national director William Ruckelshaus, and a staggering amount of Field Offices, including Minneapolis, Rapid City, Washington DC, Phoenix, Sacramento, Cleveland, Denver, Oklahoma City, Cincinnati, San Francisco, Buffalo, Los Angeles, Baltimore, and New York City. The American Indian Movement had the FBI’s full attention.

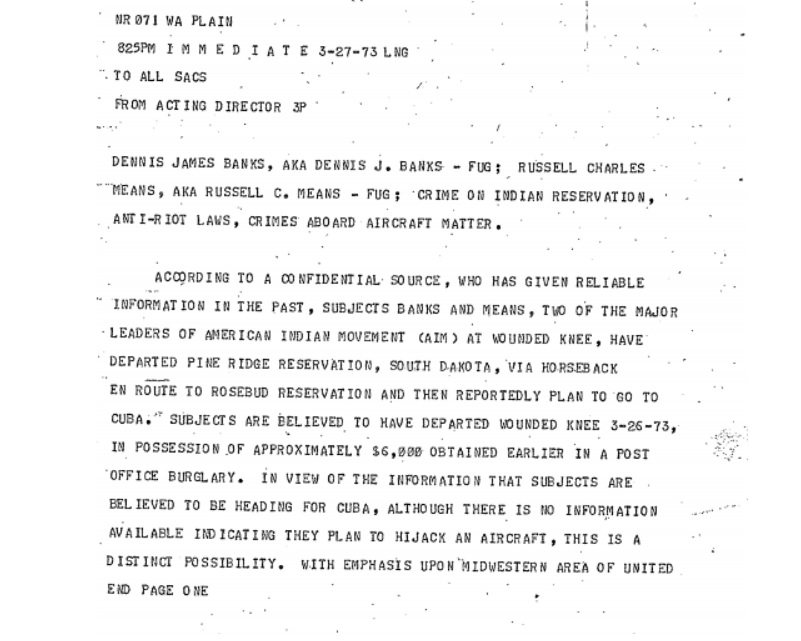

Field Offices were instructed to be doing daily teletypes about Means’s location. One theory the Bureau had developed was that Means would hijack a plane with Dennis Banks, and flee to Cuba.

On April 14th, Means was in Washington, DC, to give a speech at a fundraiser, imploring donations and speaking of the historical injustices visited upon American Indians by the U.S. government. Means was in Cleveland four days later, giving an interview to Channel Five News, again asking for contributions, reiterating AIM’s opposition to the broken treaties, and warning that if the U.S. would not negotiate, there would be another massacre at Wounded Knee. On April 20th, he gave a talk at Case Western University.

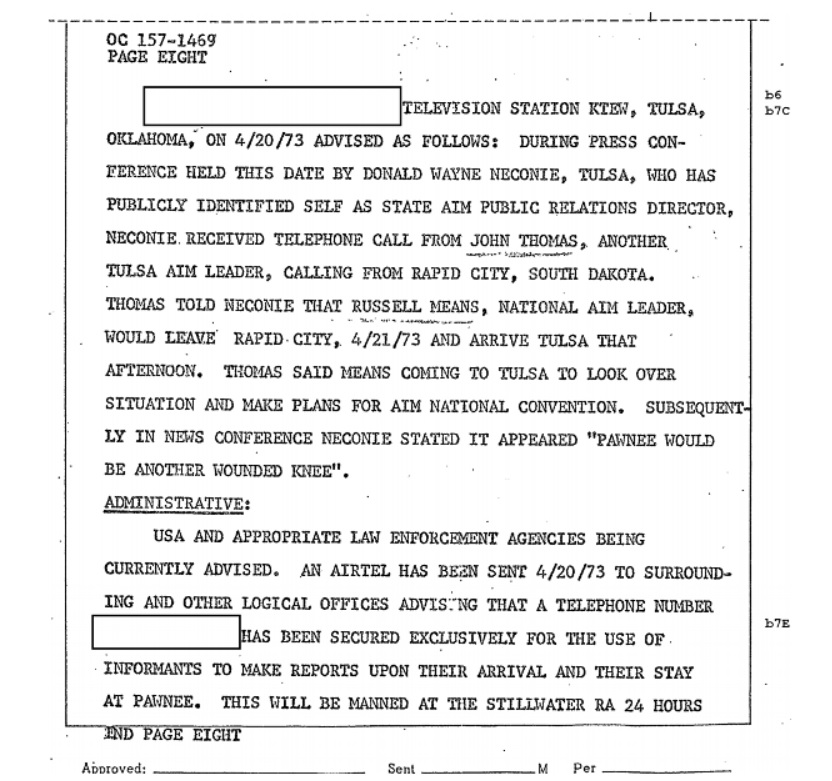

After giving the speech at Case Western University, per his itinerary, he was supposed to head to New York City for a few days - instead, he headed south to Tulsa. From there he headed to Pawnee, Oklahoma, the location of a proposed AIM national convention on the Pawnee Tribal Lands outside of town. A hospital worker in Pawnee informed the FBI that there were serious divisions in the Pawnee community there about whether to support the AIM or not. Means and other AIM leaders hoped to recruit at least five Pawnee for the struggle in Wounded Knee.

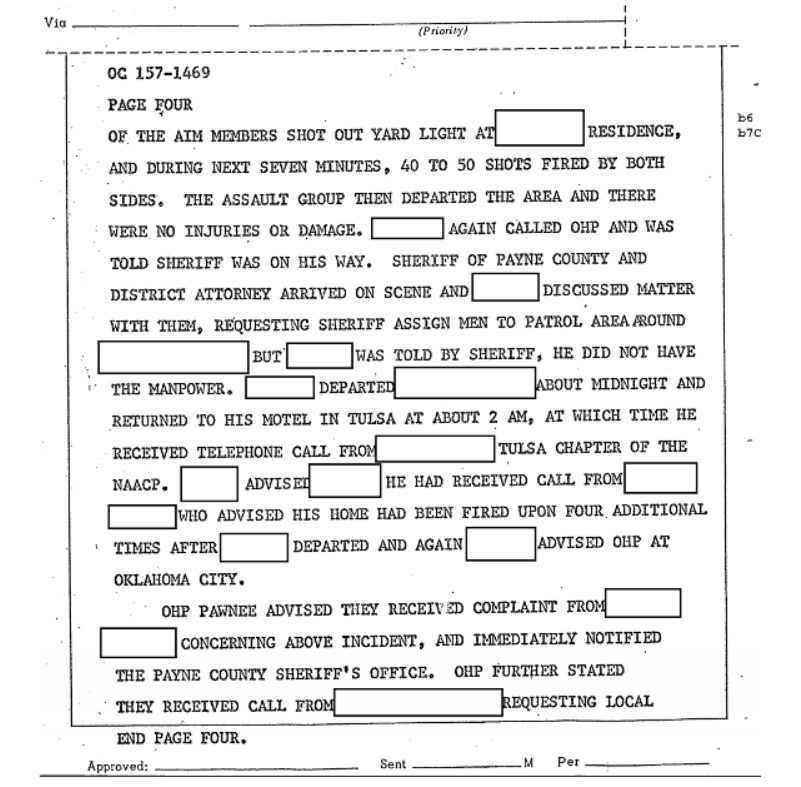

Days before Means arrived, armed AIM checkpoints were put up. That night two cars drove by and started firing shots. The men at the checkpoints rushed out screaming for people to take cover. Between 40 and 50 shots were exchanged between the AIM and their attackers over the course of the next seven minutes. Afterwards the AIM made plans to meet with the National Lawyer’s Guild and the ACLU. Target practice was begun, and the AIM public information director Donald Neconie said it appeared “Pawnee would be another Wounded Knee.”

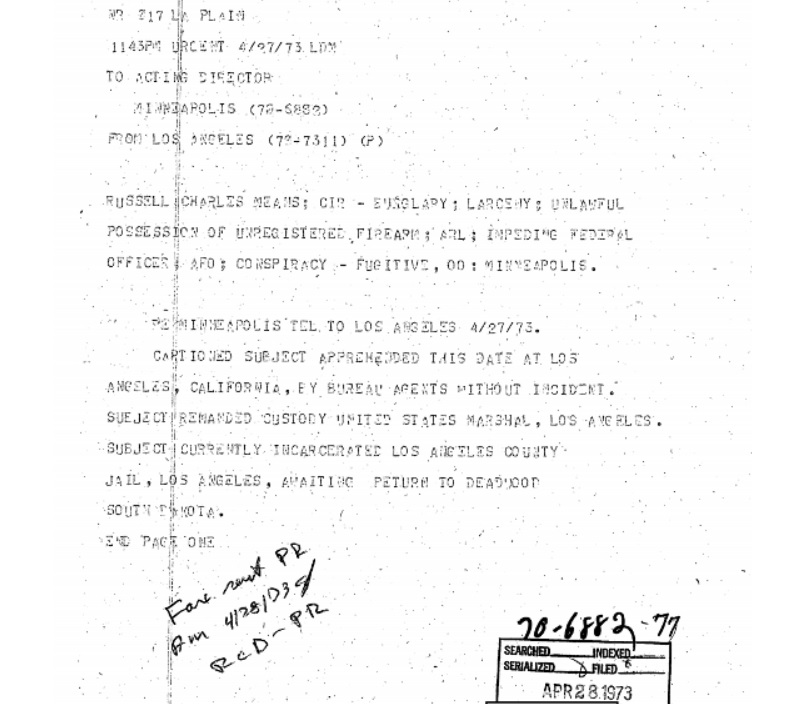

This was not to be, as the apprehension of Wounded Knee occupation leaders would commence in the weeks to come. After his stay in Oklahoma, Means was reported by the Baltimore FBI Field Office to have missed a speech on April 26th at the University of Maryland, College Park. Another source told the Los Angeles Field Office that he had given a “low key” speech on the 26th, but at UCLA. Whether it was diversionary, or a last minute change, on April 27th 1973 on his way to a press conference at the Los Angeles American Indian Center, to “make himself a martyr” as the FBI put it, Means was arrested by Bureau agents for violating the terms of his bond agreement. The Los Angeles Field Office had been well aware of his presence in the area, helped by a tip from the Phoenix Field Office.

While charges were dropped after a nine month trial in 1974, for prosecutorial misconduct no less, his arrest still meant the end of action at Wounded Knee for Means. Per information the FBI had collected, he was planning to attempt reentering Wounded Knee on the 28th, likely with supplies in tow. He also had other speaking arrangements set up with colleges around the country in May. On April 26th, just a day before his arrest, a local Lakota man Buddy Lamont was shot and killed by a government sniper in Wounded Knee. Tribal elders soon called a halt to the action, and by May 5th both sides had reached an armistice agreement and the AIM began to withdraw.

Russell Means was fiercely committed to his beliefs and his people, and was unapologetically willing to fight for his people’s survival. He is a stark and honest reminder of the utter failure that the U.S. government has been to Indigenous peoples. His 1980 Mother Jones piece is a worthy testament to his values. Give the rest of the FBI files a read below as well, and learn more about the occupation and the FBI’s intensive investigation.

Image by Neeta Lind via Wikimedia Commons and licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 2.0.