Starting in March of 1992, the U.S. has imposed economic sanctions against North Korea, aimed at forcing the nation to end its nuclear weapons program. While this policy of embargo has been pursued for 25 years, it has utterly failed to stop the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea from realizing its goal of attaining nuclear weapons.

The regime in Pyongyang has always viewed nuclear weapons as the most important weapon of the modern age, the only weapon through which deterrence of a U.S. or U.N. attack could be realized. In fact, the Juche ideology that drives the nation cites self-sufficiency in their own defense as the number one priority, and one that can only truly be gained from nuclear weapons.

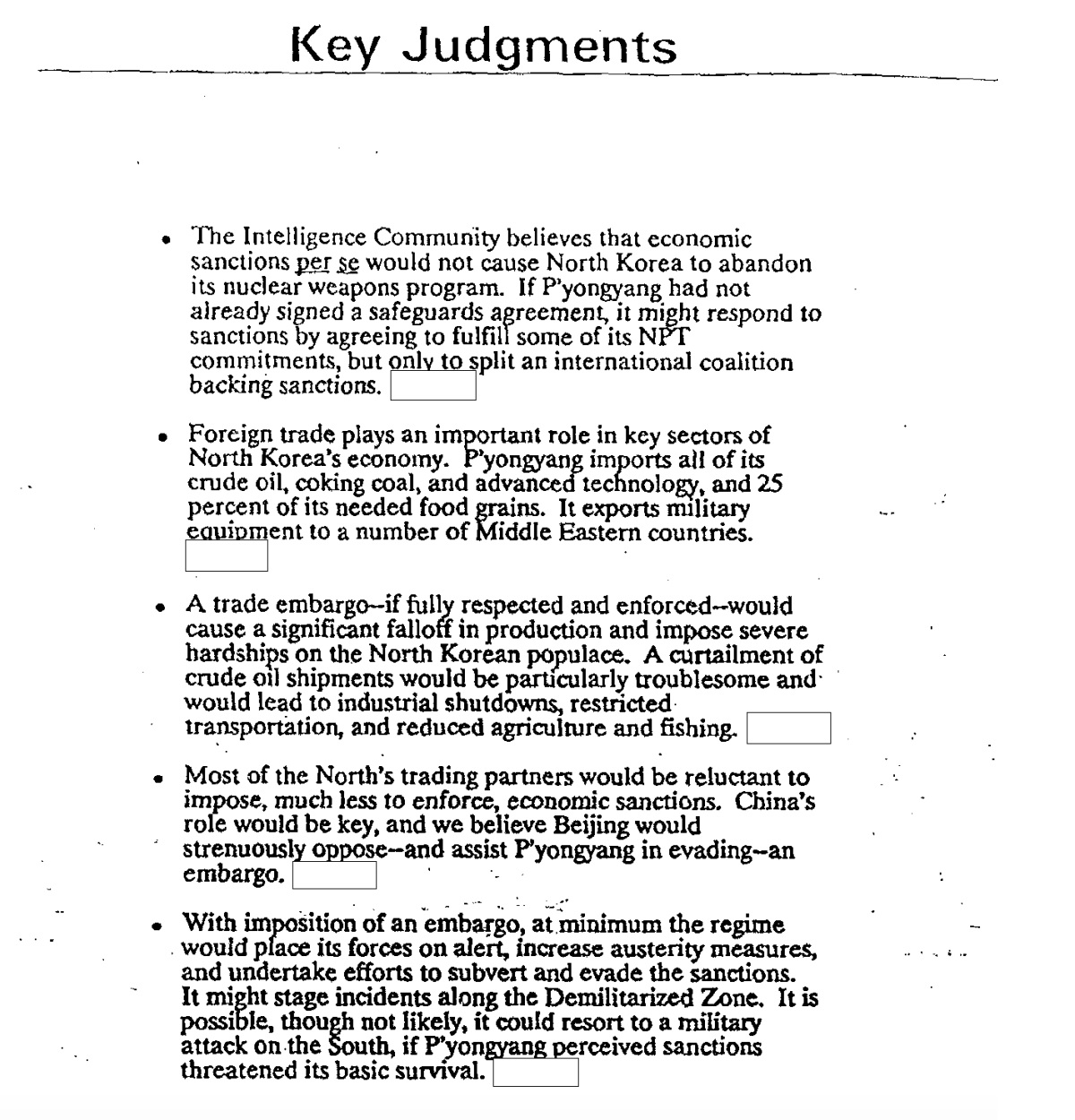

In December 1991, the National Intelligence Council put together a report entitled “North Korea: Likely Response to Economic Sanctions.” The report, which was compiled with the help of the Central Intelligence Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the Department of State, very clearly shows that the U.S. intelligence community did not think sanctions would help put an end to the DPRK nuclear weapons program. Under the “Key Judgements” section, which opens the report, the very first thing as you will see, indicates that sanctions would not be effective.

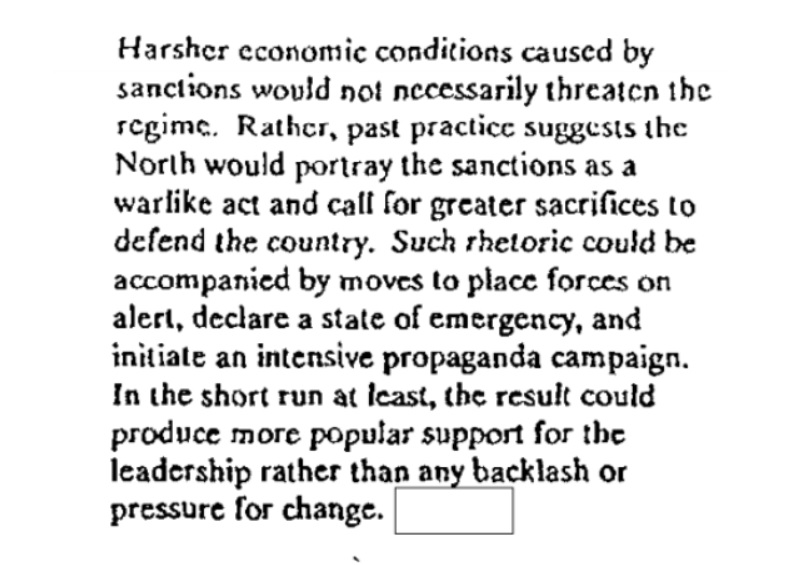

Not only would it make things more dangerous in the Korean Peninsula while also not ending the program, the NIC report argues that sanctions would likely increase support for the Kim regime.

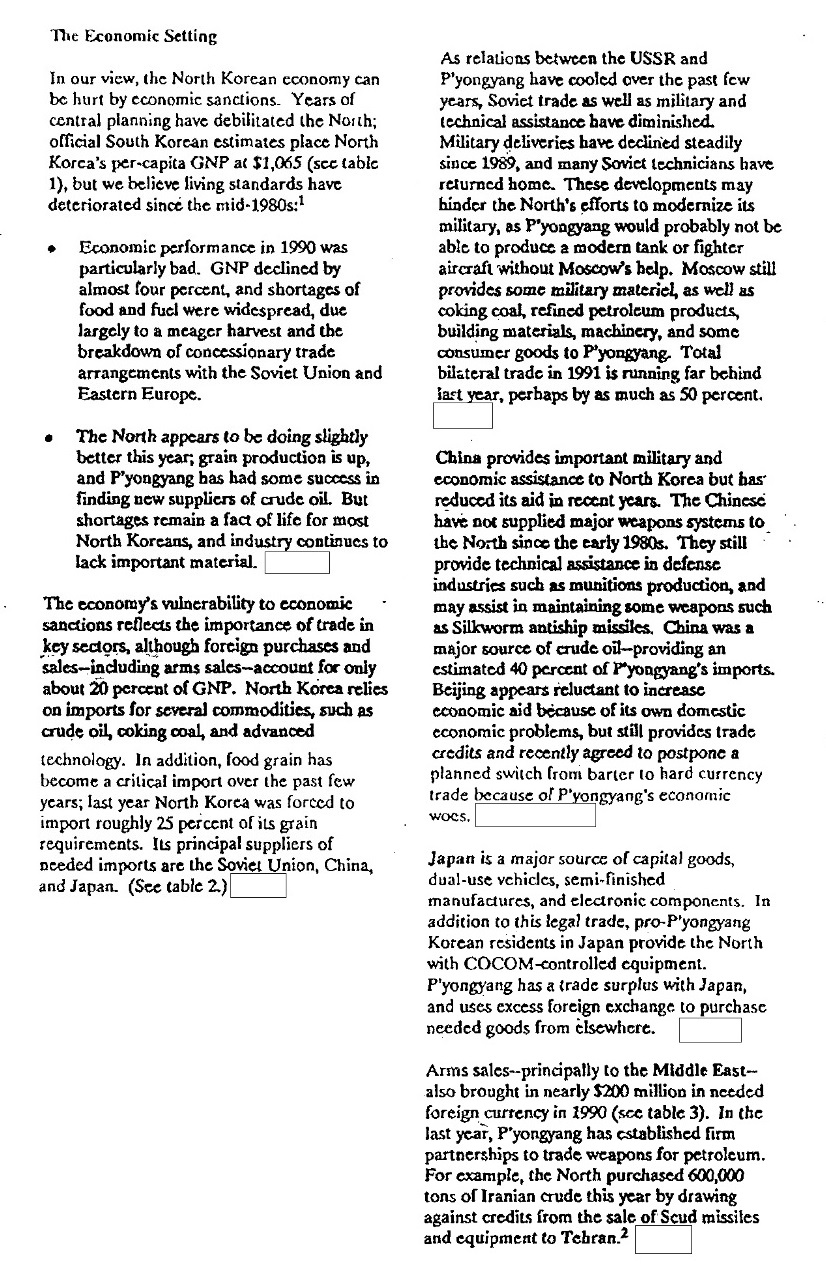

Under the section titled “The Economic Setting,” things take an even more disturbing turn. The opening sentence is “In our view, the economy of North Korea can be hurt by economic sanctions.” The NIC believed that since the mid ’80s, the DPRK economy had suffered a significant downturn, and the per-capita GNP was down to $1,065. In 1990 the report notes that “shortages of food and fuel were widespread, due largely to a meager harvest and the breakdown of concessionary trade agreements with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.” China had reduced its aid in recent years, as had the Soviets. Industry in the DPRK frequently lacked important materials for production, and crude oil was becoming increasingly difficult for the nation to procure.

In the portion of the report titled “Impact of an Embargo,” the NIC accurately predicts that “A trade embargo - if fully respected - would compound the problems plaguing the North Korean economy and would impose severe hardships on the North Korean populace.” This would turn out to be all too true. In 1994, two years after the initial round of sanctions, the embargo contributed to North Korea suffering a famine that would last until at least 1998, although some consider it to have lasted until 2002. Death estimates range from 300,000 to 3.5 million, with the U.S. Census Bureau in 2011 stating that they felt the deaths were likely between 500,000 to 600,000 between 1993 and 2000.

According to this report, the U.S. intelligence community was acutely aware of what horrifying damage could be done to the people of North Korea with a trade embargo. The report very specifically outlines the chain reaction which would occur once sanctions were imposed, with crude oil being the first crucial domino to fall, leading to the shutdown of essential industries, and eventually leading to significant setbacks in the agricultural sector as a result of no pesticides and fertilizers being created due to the lack of oil. With no grain importations, the NIC predicted that the people would be hard hit by lack of food, noting that even in 1991 citizens were on a two meal a day ration, and the country would need to import half a million tons of grain to keep levels where they were at.

Then there’s this bit, dealing with the potential international response to sanctions:

The NIC clearly felt that DPRK’s trade partners would balk at the idea, and would likely be driven closer to Pyongyang as a result. It is hard not to find all of this quite stunning in retrospect, with 25 years of sanctions now behind us. Not only did the U.S. know it would be making a humanitarian crisis much, much worse, it also knew that a trade embargo could potentially create a war between China and the U.S., or at the very least would likely increase Chinese support for the Kim regime. Even South Korea did not want sanctions at the time, feeling they were far too dangerous, and would destroy any chance for a constructive dialogue.

Needless to say, the U.S. ignored this NIC report and imposed sanctions, which resulted in many of the events warned about in these pages. Dialogue became sparser and coarser, a famine ravaged DPRK, and China was indeed driven further towards North Korea. Today China makes up 90% of North Korea’s trade volume. And to top it off, as the NIC correctly predicted, the sanctions failed utterly to stop the DPRK nuclear weapons program.

Despite all that, it appears we haven’t learned anything - just this September, President Trump announced an expansion of sanctions against the DPRK.

Read the full report embedded below.

Image by Devrig Velly via Wikimedia Commons and licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.