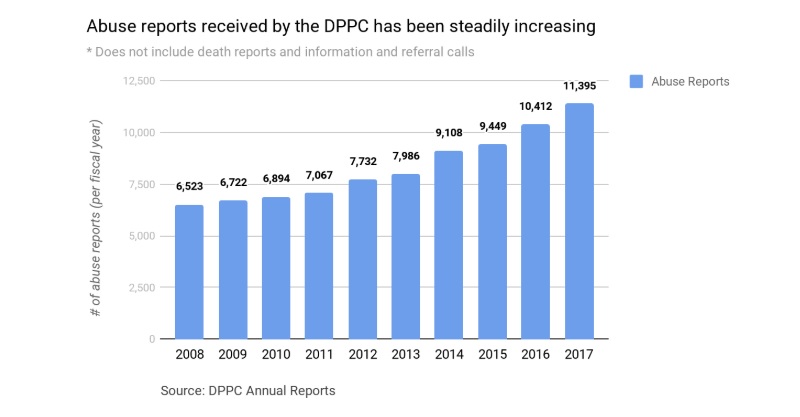

Despite the growing number of reported abuses against adults with disabilities in Massachusetts, the agencies responsible for responding to complaints haven’t been able to staff up at a comparable rate.

“We don’t have the resources and the funding that we need,” said Mariah Freark, assistant general counsel with the Disabled Persons Protection Commission. DPPC is one agency that handles adult protective services in the state, which splits the responsibilities between a number of different departments, unlike some others that consolidate adult protective services under one department umbrella. In Massachusetts, adult protective services is bifurcated - DPPC handles adults with disabilities ages 18 to 59, while the Executive Office of Elder Affairs is responsible for those 60 and older, including both individuals with disabilities and vulnerable adults.

In contrast, the number of abuse reports has been steadily increasing, growing by 20 percent in just the past two fiscal years. Staff numbers in the DPPC, meanwhile, remain relatively stagnant.

The DPPC attributes the increase in reported abuses, at least partly, to their “significant outreach and education,” Freark wrote via email. Successful awareness campaigns, though, don’t provide the resources to address the actual abuse. With hiring at a standstill, there is the potential for caseload numbers to skyrocket once again if the department isn’t able to hire more investigators.

The DPPC doesn’t handle all investigations for adults under its jurisdiction; they simply do not have the resources to perform all the investigations themselves. DPPC - with only four hotline operators, four investigators, and six oversight officers of their own - utilizes investigators in other state departments, primarily the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), the Department of Mental Health, and the Massachusetts Rehabilitation Council. As of March 2018, there were about 50 APS investigators in Massachusetts: four with the DPPC, 27 with DDS, seven with MRC, and 14 with DMH, which, according to Freark, may hire four more. The same statute that formed DPPC in 1987, M.G.L. c.19C, also established this process.

“This is the system that we have always known,” said Freark. “It’s what we were built to work with. I think we have developed a lot of good internal processes and procedures to oversee these cases and make sure that we’ve got a finger on all of the pulses.” According to her, caseloads at the DPPC are at about 30-45 cases per investigator per year and 112.8 cases per oversight officer, Freark said.

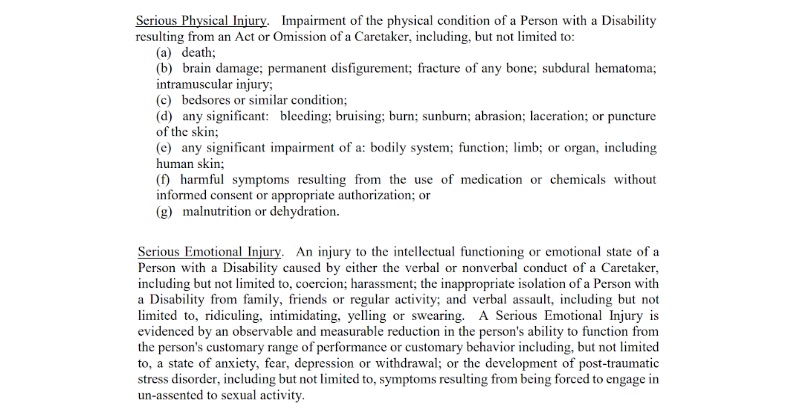

DPPC investigates reports of abuse according to guiding principles of 118 CMR: the person must be between the ages of 18 and 59 and have a disability (in accordance to the statute), the abuse must happen to a Massachusetts resident no matter if it’s in or out of state or to a non-Massachusetts resident in the state by a caretaker which results in “serious physical injury or serious emotional injury” to the person.

While most of the requirements are clear and straightforward, what is considered to be a “serious physical or emotional injury” seems to be more of a gray area.

Definitions set forth in 118 CMR 2.02:

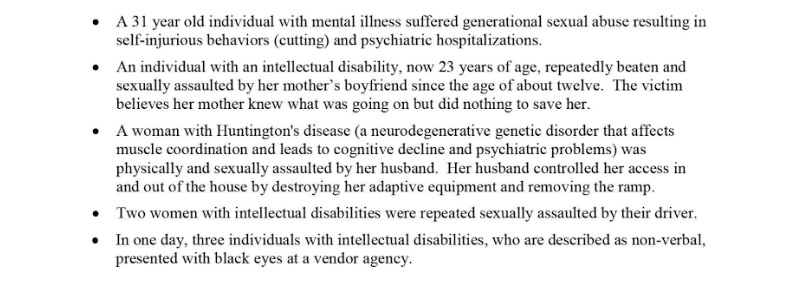

The DPPC Annual Report from 2014 gives a glimpse into the kinds of cases that the department investigates:

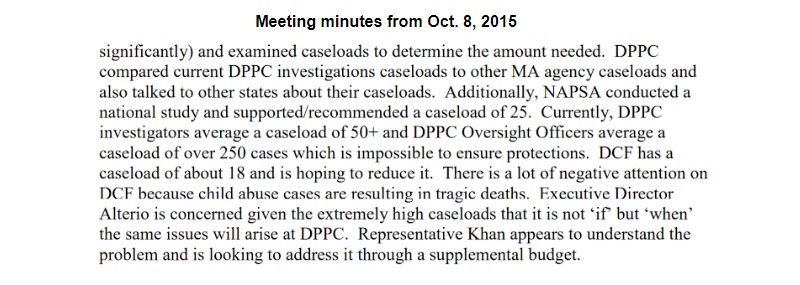

Troubling cases of legitimate abuse, like these, have the potential to fall through the cracks, as the DPPC Commissioners have previously noted:

The contrast between resources available versus the growing demand raises the question: Will a horrific case of abuse fall through the cracks? And is it still, or could it be, a matter of not “if,” but “when?”

In FY 2017, DPPC received a total of 11,395 abuse reports statewide. EOEA, which handles investigations for those over the age of 60, in FY 2016 (the most recent EOEA Annual Report available), screened 17,014 calls for cases of abuse.

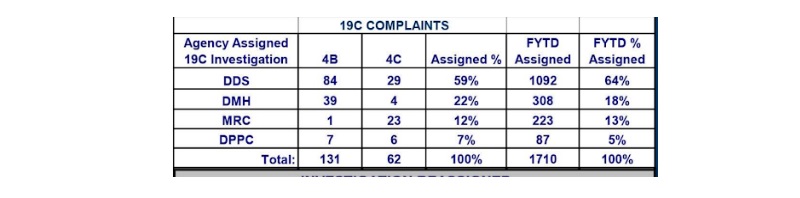

Despite their current heavy caseload, though, DPPC has only handled 5 percent of investigations so far this fiscal year (since June 2017, as disclosed in the February 2018 Activity Report. DDS (64 percent) handled the majority, followed by DMH (18 percent) and MRC (13 percent).

The DPPC has acknowledged multiple time the need to hire more staff. DPPC documents, including meeting minutes and reports, note the excessive caseload per investigator/oversight officer. Such as the DPPC Commissioners’ meeting minutes from September 7th, 2017:

When asked if the department has ever considered consolidating all facets of APS specifically under DPPC, Freark said that while there may have been mentions of it in the past, there hasn’t been any serious consideration.

“At this point, consolidating would require a significant overhaul of [the Executive Office of Health and Human Services] and DPPC itself. I don’t think anyone has ever contemplated a budget that would allow for it.”

Of course, the lower the caseload per investigator and oversight officer, the lower the risk of something being overlooked or missed, but it’s hard to come up with an “ideal” number, Freark said. A general lack of uniformity among APS across the country makes it hard to compare each state.

“Only recently the Administration for Community Living came into being,” Freark said. “They’re within the federal Department of Health and Human Services. That’s the first attempt at consolidation and federalization of APS that we’ve seen. Each state develops its own way of doing APS. How those investigations get handled vary state to state, and county to county depending on what state you’re talking about.”

Even if caseload numbers go down, the concern will never be completely erased, according to Freark, because of the nature of the work and budget issues that beyond the department.

“It’s not just DPPC, but the system itself,” Freark said. “The other three agencies that are providing the protective services are chronically under resourced and underfunded.”

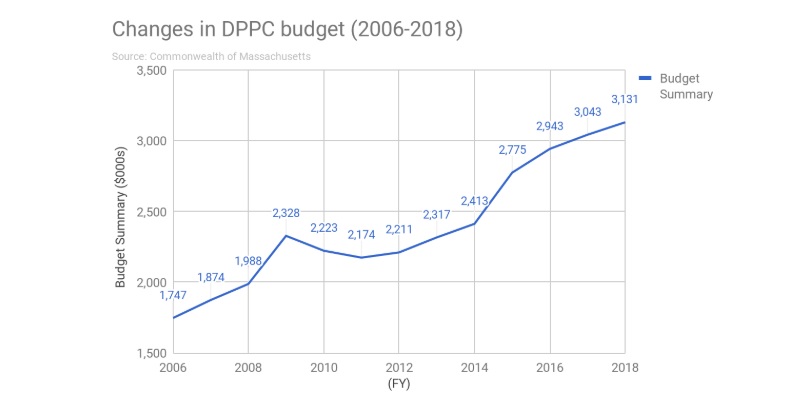

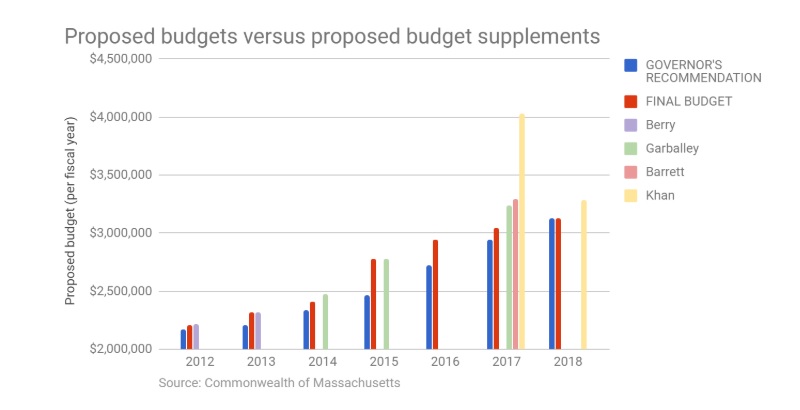

While the budget has slowly been increasing over time, it mainly accounts for rising costs and inflation without providing the boost that the department needs.

More recent efforts to supplement the budget have not succeeded:

- An increase of $100,000 for FY 2018, sponsored by Sen. Michael Barrett (D-MA)

- An increase of $1.1 million for FY 2017, sponsored by Rep. Kay Khan (D-MA)

- An increase of $294,000 for FY 2017, sponsored by Rep. Sean Garballey (D-MA)

- An increase of $250,000 for FY 2017, sponsored by Senator Barrett

- An increase of $130,000 for FY 2014 by Representative Garballey

- An increase of $40,000 for FY 2012, sponsored by former Sen. Frederick Berry (D-MA)

But a few past efforts were successful. DPPC’s budget increased by $314,000 for FY 2015, sponsored by Representative Garballey, and increased by $64,000 for FY 2013, sponsored by former Senator Berry.

“We consider our work to be a priority and we at least want to keep the staff we’ve got and not have to lay anyone off, if not get more people, but ultimately that not up to us,” said Freark. “We do what we can on our end.”

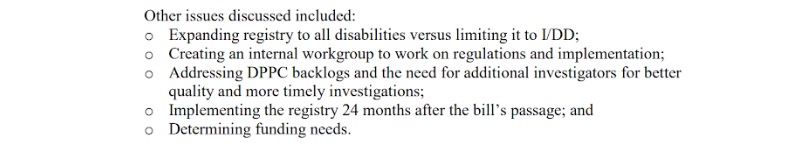

The DPPC’s meeting minutes from 2015 are embedded below, and the rest can be read at on the request pages above.

Image via Robins Air Force Base