A senior New York City environment official overseeing its wastewater surveillance program for signs of the coronavirus, mpox and polio said the data is “becoming more and more useful for tracking illnesses,” but that the city has a ways to go before using it to inform public health. The reason? The city’s health department and other agencies haven’t fully bought into the wastewater program as a trusted source for decisionmaking.

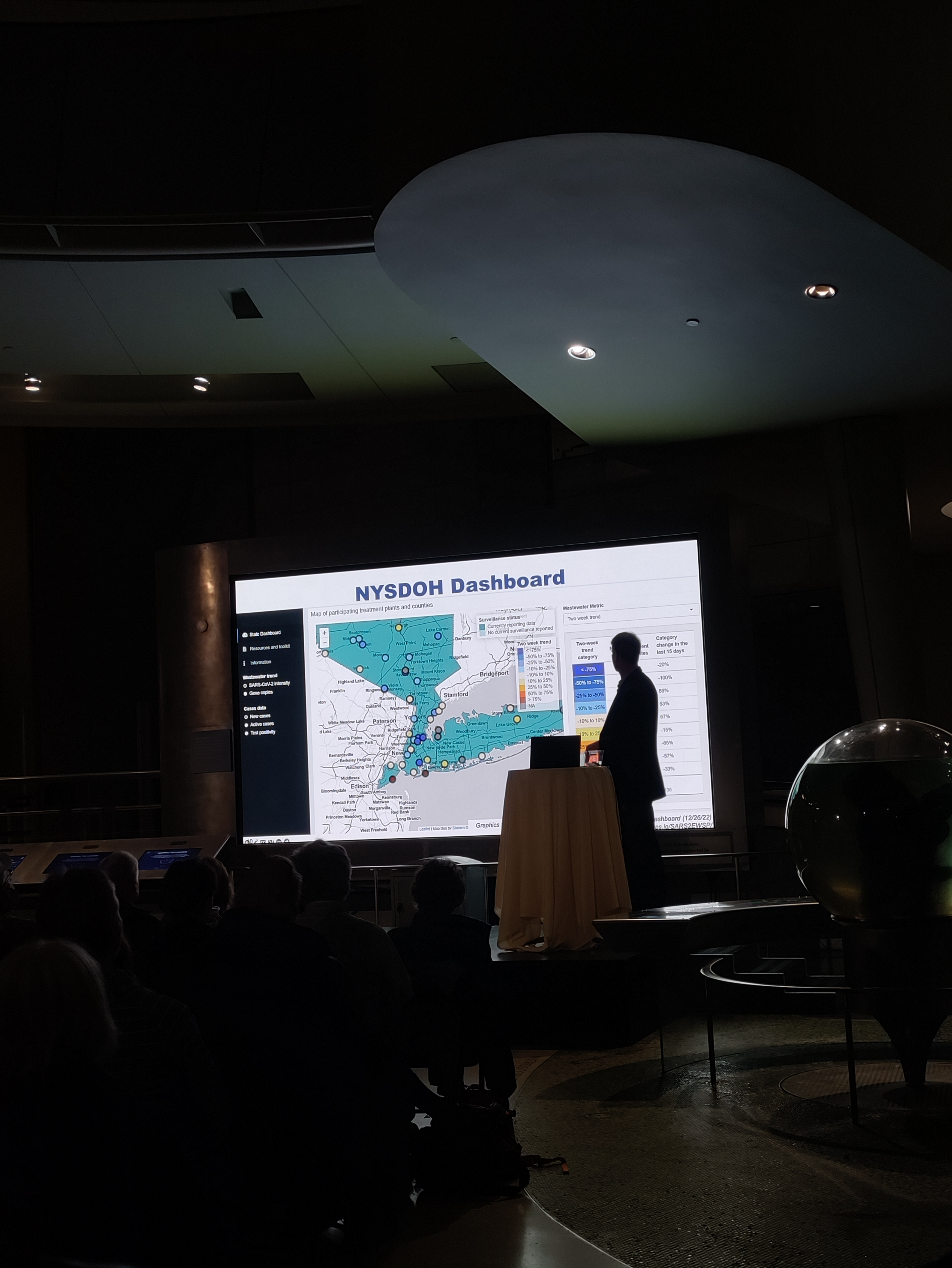

The comments came Wednesday during a presentation at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan by Jonathan Hoffman, director of regulatory compliance for the NYC Department of Environmental Protection — and represent a sharp departure from a joint statement made last month by the city’s health and environment agencies, which called wastewater surveillance a “developing field,” stressing a need for further research before it could be used to inform policy action.

Hoffman told a crowd of museum members and self-described science nerds that wastewater is becoming more useful as fewer people get the lab-based PCR tests that are reflected in the city’s COVID-19 dashboard. The talk was part of AMNH’s SciCafe monthly event series, in which experts from the museum and other city institutions provide informal overviews of new science topics.

Analysis by Gothamist and MuckRock found that, as PCR testing declined in 2022, data from our sewers showed a higher level of coronavirus spread than official case numbers – suggesting that the sewer data may be more accurate. Currently, the city’s testing rate is the lowest that it’s been since May 2020, despite COVID-19 hospitalizations steadily rising in recent weeks. This pattern also suggests a disconnect between traditional PCR testing and what’s happening out in communities, with many people turning to more-convenient at-home tests.

Wastewater testing doesn’t rely on individuals going to the doctor to get tested, Hoffman said. It also protects individual privacy, since hundreds of thousands of people are tested at once. “In terms of time and money and staff, [wastewater testing] is a lot quicker and easier and cheaper” compared to testing people one-by-one, he added.

In response to an audience question about why New York City’s wastewater program hasn’t been better publicized, Hoffman cited challenges among public health departments on “buying into” the new type of data represented by sewer testing. This population-level, environmental information is “a really big departure” from the case counts that health officials are used to using, he said.

In a statement last month, city health and environmental agency officials suggested that New Yorkers should continue to rely on case counts, rather than the sewage monitoring to gauge coronavirus rates, contrary to many other major U.S. cities and states, such as Boston, the Twin Cities and San Diego. At the time, the agencies were responding to an investigation by MuckRock and Gothamist that revealed limited public sharing of the city’s wastewater data and little action by officials, despite $1 million spent on the sewage monitoring program over three years.

New Yorkers can currently find city wastewater results – with some delays – on dashboards run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and New York State, as well as on the city’s OpenData portal. When asked if city agencies are working on a local dashboard or other outreach efforts, Hoffman said that this type of communication work is primarily up to the health department.

“Wastewater analysis is a valuable tool and something we integrate into our broader surveillance effort,” health department spokesperson Patrick Gallahue said via email. “The sampling has helped us enrich our already robust COVID surveillance but also informed our public alerts on the polio virus.”

In 2023, city environmental protection officials will continue to collaborate with the CDC, other agencies and academic partners on wastewater surveillance, Hoffman said. This could include expanding to new health threats, though the environmental and health departments have not yet determined which diseases or other biological markers might be next in line for tracking. It could also mean testing in more precise geographic locations, to better identify where a disease is spreading.