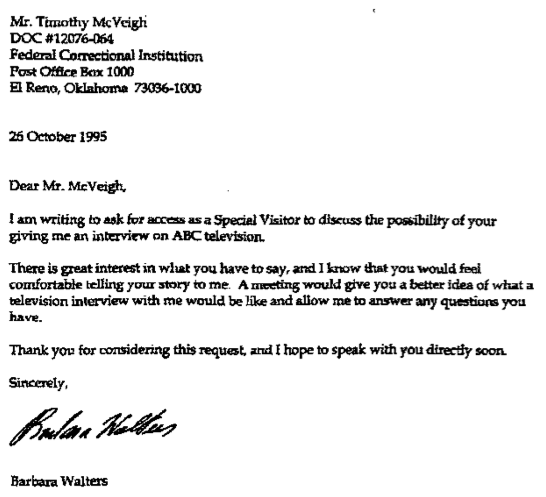

Timothy McVeigh, a 27-year-old Gulf War veteran, was savvy about the choices before him. He had scores of journalists begging for an interview, and this note from ABC’s Barbara Walters was one of the many he decided to grant after his capture on the side of an Oklahoma highway and a few months before his 2001 execution by lethal injection.

McVeigh’s federal 1,800-page Bureau of Prisons file, released to MuckRock user Jason Smathers after a two-year wait, reveals even the most minute aspects of McVeigh’s life on death row. It’s dominated by media requests that reveal how far journalists would go to to put McVeigh in front of an audience.

McVeigh’s bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in 1995 was the worst incident of domestic terrorism up to that point in U.S. history, killing 168 people and injuring more than 600 others. The Oklahoma City bombing also happened during a watershed moment in American journalism, when the emerging 24-hour news cycle gave McVeigh an unprecedented platform.

While fame stemming from a heinous crime is as old as journalism itself, McVeigh’s stern grimace had a worldwide reach and was a sought-after commodity until he stopped accepting requests a few months before his execution.

In their pleas for access, journalists ranging from world renowned pillars of the craft to unknowns looking for a big break who said whatever they thought would get McVeigh talking on the record. From the first requests he received, it was clear journalists weren’t squeamish about playing on the vanity and the ideals of a man who had blown up a truck next to a daycare center.

In 1995, harkening back to his days in the U.S. Army was the most popular — and successful — approach.

“We shook hands in the Gulf,” NBC’s Tom Brokaw wrote in 1995. “Now, I’d like to sit down with you and talk at length.”

In 2001, as McVeigh’s execution neared, the pleas focused on maximizing exposure.

“If it’s a big audience you’re after,” a journalist for WB 33 wrote, “I can deliver.”

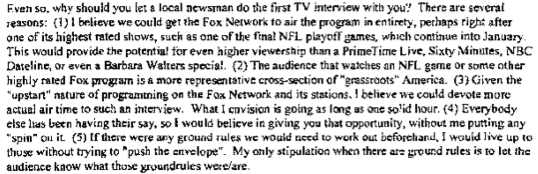

A November 1995 list of authorized visitors included heavy hitters from the major networks, a New York Times reporter and Jack Bowen of Fox 25 KOKH. McVeigh apparently responded well to the local reporter’s pitch, in which Bowen cast himself as the underdog.

“Granted, I’m not Barbara Walters or Dan Rather or one of the big network people,” Bowen wrote. What I am is an ordinary guy who grew up in West Texas and works hard in the trenches as a true journalist to be more than a reader, and who believes in asking the tough questions, but asking them with dignity and respect, and then reporting the results fairly.

I don’t drive up in a limousine, I don’t have a producer working for me, and I help carry in the heavy TV equipment whenever I do an interview. I do all the research, so there’s not much chance for somebody other than me to make a mistake on my work. Because of that, I feel all the more responsibility to ‘get it right.’“

Aside from his own credentials, he explains the appeal of Fox:

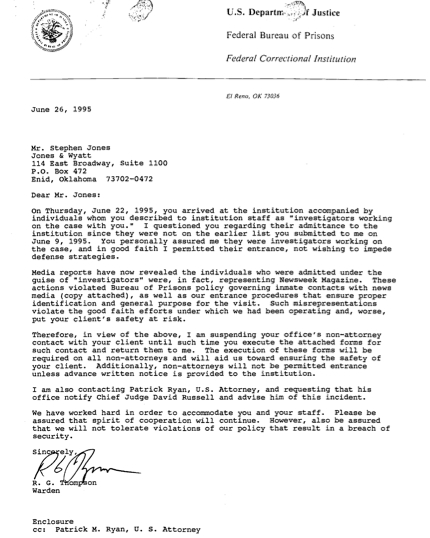

There is only one immediately obvious instance of a media representative accused of not playing by the rules in order to gain access. Retired Army colonel and Newsweek contributing editor David Hackworth first gained McVeigh’s attention as the author of the bestselling “About Face,” which he sent along to McVeigh.

“After reading, I would like you to consider allowing me to come visit you for the purpose of doing a soldier-to-soldier interview for Newsweek magazine,” Hackworth wrote. “Obviously you should run this request by your attorneys. I reckon somewhere along the line you’ll want to tell your story, and I think a good starting place would be another story who has been there, as you have.”

A few weeks later, Hackworth and another Newsweek representative were granted access to McVeigh as part of his legal team. A letter from El Reno prison Warden R.G. Thompson explains that he felt misled, and was revoking non-attorney visiting privileges:

McVeigh’s attorney, Stephen Jones, countered with a letter that stated Hackworth was aiding the legal case by reviewing McVeigh’s military records, “a statement which is absolutely true.” Either way, he said Hackworth should have been recognized, noting, “This is all the more puzzling to me because Colonel Hackworth is a contributing editor to Newsweek and there are at least 4 or 5 issues of Newsweek in your reception area.”

The looming execution brought more media requests to McVeigh than ever. Journalists from across the world, at publications and stations that ranged from major dailies to small-town talk shows, sent hundreds of requests asking for, as one station from Colombia put it, “at least a few words from him before he died.”

The tactics seemed to shift from “soldier-to-soldier” or “I don’t drive up in a limousine” to pitches that either made claims of large audiences or unfiltered airtime, as Cleveland area WTAM offered.

McVeigh’s authorized biography, “American Terrorist,” written by Buffalo News reporters Lou Michel and Dan Herbeck, was what McVeigh chose to serve as his official statement to the media. It was published in April 2001, two months before his execution. While it addressed many questions about his life and motivations behind the bombing, many networks insisted it was wasn’t enough. As one BBC reporter put it:

While the vast majority of the mail in McVeigh’s file is from media requests, McVeigh received correspondence from the public as well. One letter shows that no matter how much coverage McVeigh received, it didn’t help one victim’s mother piece together his intentions. In February 2001, she wrote pleading that he would help her understand.

“I am the mother of [redacted] died in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on April, 19 1995,” she wrote. “That day, my life was changed forever. There have been many changes, not only for me but for my entire family. One of the most difficult things we have had to cope with, however, is the fact that not only was [redacted] taken away from us, but we have never figured out why it happened. Knowing ‘why’ will not bring her back, and it will not give me ‘closure’ — but it will help me.”

“I followed the trial carefully. I know what is in the court records. I know what the jurors said after the trial. They said you were guilty. But that can’t be 100% real to me until I have heard it from you personally.”

“I have harbored a dream for almost six years now that one day I would be able to sit in a room with you and ask you questions that would help me to understand why [redacted] had to die.”

The mother lists a series of piercing yet sensitive questions asking about how McVeigh went from decorated soldier to disaffected veteran, noting that she “tried to imagine what might have been going through your mind as you sat on the hood of your car watching the Branch Davidian compound in Waco burn down, knowing there were people in that complex.”

“If I were sitting across a table from you,” she concludes, “I know I would find it difficult to think of all the questions I would like to ask, just as I find it difficult to even write them down. But I hope you can imagine how strong my need to know and understand is, and always will be. I hope and pray that you will answer my questions. You are the only one who can do it, and our time is running out.”

Over the course of six years, there was a record of the response to each media request. There is no record of whether McVeigh answered this letter.

Read the full file embedded below, or on the request page.

Image via NY Firearms