The Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office (MCSO) near Houston, TX has owned its Shadowhawk UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) since October 2011. Like other law enforcement drones across the country, MCSO’s was funded by Department of Homeland Security grants and packs powerful video and thermal imaging surveillance equipment. But at 29 pounds and seven feet long, the jet fuel-powered Shadowhawk unmanned helicopter not only dwarfs the UAVs of peer departments, but exceeds the weight limit set by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). While the Texas Attorney General ordered MCSO to release its UAV policy to MuckRock, both the FAA and the sheriff refuse to disclose whether the department has an active drone certificate despite the weight rule.

Most unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) owned by civilian law enforcement agencies (like the Seattle Police Department’s Draganfly or the Mesa County Sheriff’s Falcon) are battery-powered and have wingspans under three feet. According to documents submitted to the FAA, the MCSO’s Shadowhawk runs on jet fuel, boasts a six-foot wingspan and weighs 29 pounds.

Its heft puts the MCSO drone over the FAA’s acceptable weight limit for public safety UAVs. An agreement with the Department of Justice last May established that civilian law enforcement agencies can receive FAA authorization to operate drones up to 25 pounds. The FAA-DOJ agreement increased the allowable weight for public safety agency drones from the 4.4-pound limit established by Congress in February 2012 under the FAA Modernization Act.

The sheriff’s Shadowhawk drew unwanted attention last year when it crashed into a MCSO armored vehicle during a demonstration and photo-op. Civil liberties advocates were also worried by the MCSO’s choice of the Shadowhawk unit itself. Vanguard Defense Industries, which manufactures the Shadowhawk, emphasizes the unit’s compatibility with non-lethal weapons systems such as tasers and bean bag “stun batons.”

MSCO purchased the Shadowhawk in October 2011 at a cost of more than $220,000, according to documents the sheriff released to MuckRock as part of the Drone Census project. Like other police departments seeking to acquire UAV technology, the MCSO received funds from the Department of Homeland Security’s Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI).

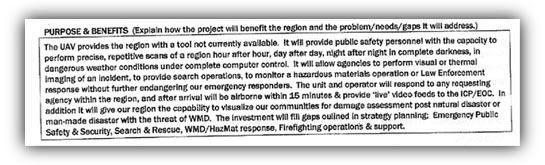

According to its 2010 UASI grant application, the sheriff proposes to use its UAV on a regional basis “to provide aerial surveillance at any critical incident involving a public safety response.” Such incidents might include disaster evacuation, building collapses, train derailments, fire emergencies, hazardous materials spills and SWAT rescues. Unlike smaller, battery-powered drones, whose maximum flight time can be as short as 15 minutes, the MCSO Shadowhawk can remain in the air “for over an hour” to provide “real time reconnaissance through both infra-red and color video [sic],” according to the UASI application.

The same application indicates that MCSO’s UAV will provide public safety personnel “with the capacity to perform precise, repetitive scans of a region hour after hour, day after day, night after night.” The Shadowhawk can perform both visual and thermal surveillance “in complete darkness, in dangerous weather conditions under complete computer control.”

Beyond its grant application and a sales quote for the Shadowhawk, the MCSO attempted to withhold its UAV policies and procedures as requested by MuckRock. The Texas Attorney General’s office rejected the MCSO’s suggestion that releasing further information could “jeopardize the lives and safety of police officers and the general public,” and ordered the sheriff to release the policy.

This “Tactical Air Unit Policy and Procedure” further codifies the purposes for which MCSO aims to use its drone, with a specific emphasis on public safety, search and rescue and tactical operations, particularly in the rural areas of the county. The SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) and narcotics units receive specific mention as beneficiaries of the technology, as these units “will utilize camera and FLIR [Forward Looking Infrared] systems to provide real time situational awareness of the target during high risk operations.”

The rest of the policy defines UAV flight crew training standards, launch procedures and maintenance requirements. The Shadowhawk apparently records its video feeds, as the video operator is tasked with “recording and retrieving saved digital data.” There is no explanation in the policy, however, of the purposes to which this data may be stored. As MuckRock has found in other law enforcement UAV policies, the MCSO protocols contain no mention of privacy concerns or probable cause requirements for drone surveillance.

The MCSO’s bold designs for tactical drone operations have been stymied so far by a limited authorization from the FAA. The most recent certificate released by the FAA authorized MCSO to operate its Shadowhawk solely within a one-nautical-mile circle centered in the extreme northwest corner of the county, far from the Houston suburbs that lie within the sheriff’s territory.

MCSO’s drone authorization, which must be renewed every 24 months, authorizes flights within this narrow zone “for the sole purpose of training and development of safety/operational procedures.” The authorization also includes the same restrictions that currently bind all public agency UAVs in domestic airspace: the Shadowhawk can fly only during daylight hours within visual sight of an observer, must remain below 400 feet above ground level and cannot conduct operations over populated areas, heavily trafficked roads or open-air assemblies of people.

The most recently released drone certificate for the MCSO expired in December 2012. Documents do not indicate whether MCSO has received a subsequent authorization from the FAA to operate its unit. The FAA and Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office refuse to discuss the authorization process or confirm whether the MCSO has an active drone certificate.

Image via Cryptome.org