As one of the oldest and largest youth organizations in the country, the Boy Scouts of America have been on the FBI’s radar since the Hoover era, when the Director helped the BSA develop a fingerprinting merit badge. The Bureau’s 500-page file spans 70 years, including recent allegations that BSA leaders manipulated enrollment numbers and even created “ghost” units to qualify for federal funding.

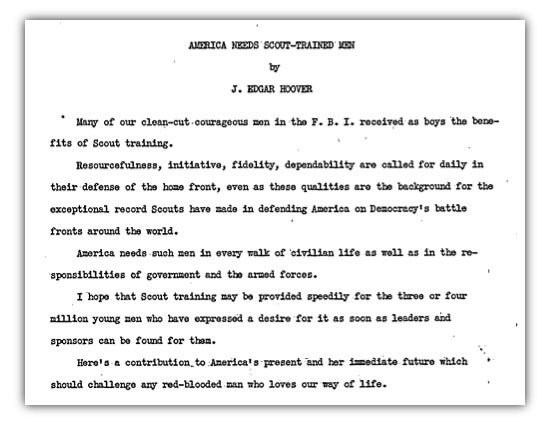

Director Hoover took a personal interest in fostering close ties between the Bureau and Scouts. He lauded Scout training for instilling “resourcefulness, initiative, fidelity, [and] dependability” in many “clean-cut courageous men” and frequently hosted Scouts for visits to FBI headquarters. One Scout father requesting a tour and autographed headshot wrote to the Director, “You must know that any boy would far rather meet you than the President.”

Hoover seized opportunities to engage Scouts in the work of the FBI. In 1937, he oversaw the drafting of a Scout fingerprinting manual as part of a new merit badge. The Director was of the view that the Bureau should get in “at the ground floor” of any youth fingerprinting efforts to “avoid outside charlatans getting a hold of a worthwhile project.”

The manual includes a brief history of criminal fingerprinting and instructions for taking prints accurately. Cards collected by Scouts at fingerprinting drives were to be forwarded to the FBI’s Civil Identification Section, where they would be maintained “entirely separate from the criminal records.”

While some of Hoover’s deputies were concerned that the Bureau might attract “possibly warranted criticism, from those antagonistic to civil fingerprinting,” the Director encouraged national Scout leadership to collect fingerprint cards for its civil database. The file mentions a handful of “discreet inquiries” Hoover ordered into critics of fingerprinting drives, including one Pennsylvania minister some suspected was an undocumented Canadian national.

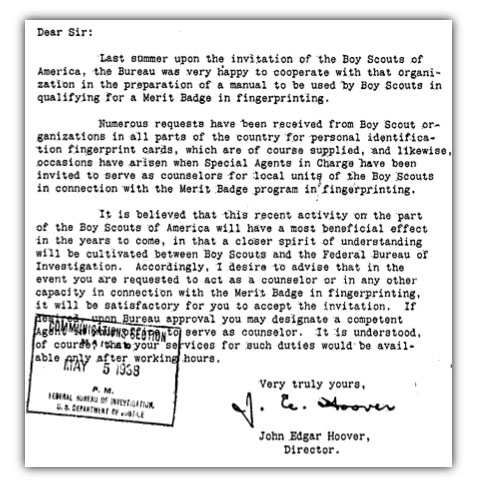

Hoover encouraged agents around the country to act as Scout counselors for the fingerprinting merit badge. In a May 1938 letter to all field offices, he wrote that “recent activity on the part of the Boy Scouts of America will have a most beneficial effect in the years to come, in that a closer spirit of understanding will be cultivated between Boy Scouts and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.”

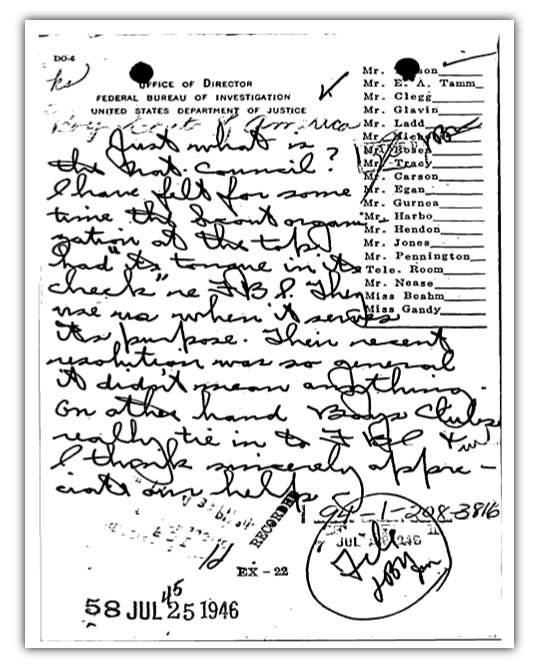

The Director expressed impatience and even scorn for BSA national leadership, whom he considered ungrateful for the Bureau’s assistance and support. When the Scouts issued a resolution of thanks in 1946, Hoover considered it “so general it didn’t mean anything.” In a handwritten memo, Hoover confessed that he had felt “for some time the Scout organization at the top had ‘its tongue in its cheek’ re FBI, [.... and] use us when it serves its purpose.” He contrasted the BSA with Boys Clubs, which he felt “sincerely appreciate our help.”

An assistant drafted a response memorandum reminding Director Hoover that he had himself been a member on the BSA National Council in the past, had been nominated to its National Court of Honor and had received its highest honor, the Silver Buffalo, just three years earlier.

Despite his apparent frustrations, Hoover continued to support the Scouts. In a live address for Boy Scout Week on NBC radio in February 1948, the Director praised the “character building and citizenship training values of Scouting.”

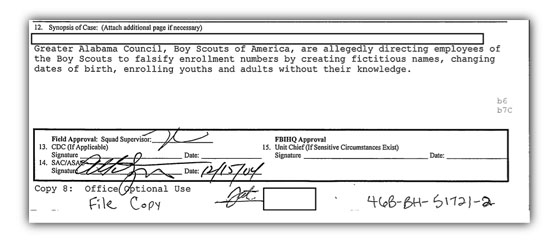

After 1948 the file jumps more than 20 years to a report from June 1969 detailing the theft of two rifles on loan to Boy Scouts in Tucson, Ariz. And while the Hoover-era (1935 to 1972) documents comprise more than 150 pages, the BSA file contains only 10 pages in total of memos and correspondence from 1969 to 2004, when the FBI began investigating the Greater Alabama Council of the Boy Scouts of America for falsifying enrollment numbers.

Through more than 40 interviews with individuals inside and outside the GAC, the FBI heard of local Scoutmasters feeling pressured by the national leadership to sustain and grow numbers and charter new troops.

“The general vibe was that the [Greater Alabama] Council would do whatever was needed in order to get by,” a BSA leader said to FBI agents in 2004.

In his testimony, the witness said Scout leaders were directed to housing projects and public schools to boost enrollment. All interested boys were given an enrollment card to fill out, but the witness said that boys that indicated on the card they were not interested were still added to the BSA roster.

“A boy’s response on the card does not matter to GAC,” the witness said. “All the boys who complete the card are signed up as Scouts.”

Other Scout leaders said that some ghost charters listed the last name for every supposed scout as “Doe.” One leader said each legitimate Scout was also listed in another troop that in reality didn’t exist.

The United Way, the National Rifle Association and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development were all supporters of Boy Scout programs in the GAC, and BSA leaders said in FBI interviews that membership numbers were muddied to get more grant money.

The NRA, for example, granted $2,500 to GAC in 2003 to purchase shotguns and .22 caliber rifles. The GAC told the NRA this money would benefit 65,000 individuals, but an after-action report updated those numbers, asserting it only benefited 2,500 individuals. One Scout leader testified that grant applications to the United Way claimed 100,000 scouts would benefit from grant money, when in reality only 50,000 would.

In other instances, however, Scout numbers were reduced for financial gain. One witness stated that at an October 2003 “haunted weekend” at the BSA Camp Sequoyah, the GAC underreported the youth and adults in attendance by 200 “for insurance purposes.”

As the FBI began taking notice of the falsified records of the GAC, witness testimony claims that “somebody on the inside” tipped of Boy Scout leaders that “the FBI was coming.” In response to this knowledge, the witness said, GAC leader locked the room containing filing cabinets in January of 2004 and replaced four computer hard drives later that year.

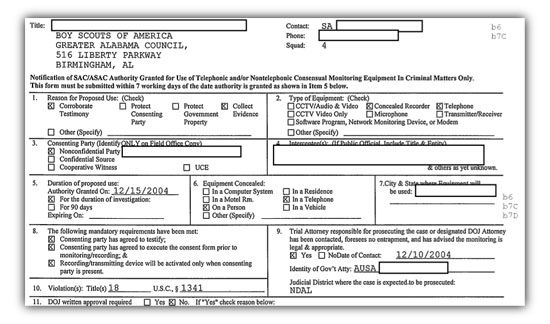

These cautionary steps did not stop the FBI, and the investigation grew. During the GAC inquiry, FBI officials interviewed BSA leaders, combed through BSA documents and tapped phone lines for evidence gathering.

Image via Wikimedia Commons