Curtis Raye is that rare comic who turns to the FBI Vault and PACER in search of material. As every FOIA nerd could predict, he doesn’t have to look far for true tales of the absurd. He just has to be patient.

For this week’s Requester’s Voice, we caught up with Raye about “FOIA Love,” his new NYC variety show that debuted this Wednesday at Manhattan’s Tank Theater. He outlines how to explain FOIA to the uninitiated, the inherent relatability of public records and the virtue of patience when requesting athlete’s FBI files.

Note: just like many public records, some of the embedded videos below contain four-letter words beside “FOIA.”

Give us some background on “FOIA Love.” How did you get the idea to use public records for comedy?

The first thing I said when the show started on Wednesday was, “I’ve been waiting to do this show for four years.” I lived in Washington, D.C. for eight years, surrounded by Beltway politics and public documents. A lot of the comedians and improvisers I worked with there were lawyers, and even though I’m not a lawyer I’ve always like talking about court cases and filings. So when I started doing comedy several years ago, the connections were easy to see. I just needed to find a way to present the information in government documents in interesting ways.

How do FOIA documents work their way into the show?

Ever since I developed the idea for the show, I’ve been accumulating documents to feature. The first I found were filings from a lawsuit against NFL player Fred Davis, who represented himself in court in 2011. Based on that document, I made athletes the theme for the first show, and went on the FBI Vault and looked up as many athletes as could think of.

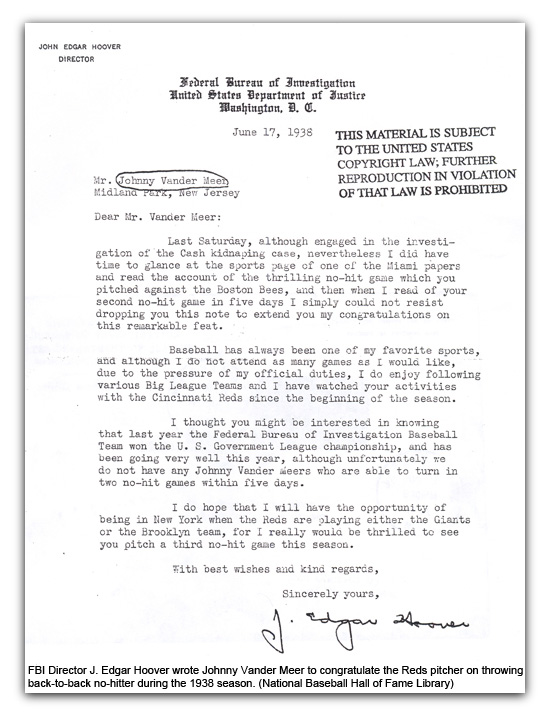

I dug up a fan letter J. Edgar Hoover sent to his favorite pitcher:

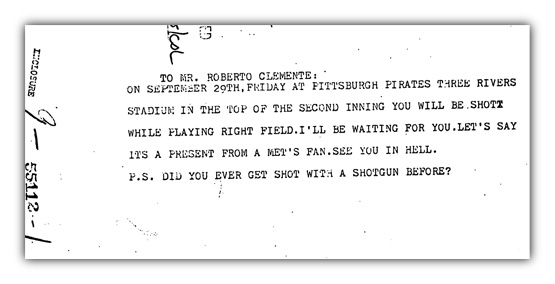

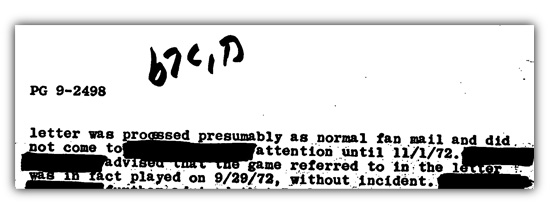

And a bumbling death threat letter to Pittsburgh Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente, who apparently didn’t even see the letter until a month after his stalker was to strike:

I also submitted a few FOIAs of my own to the FBI, and actually just got a letter in the mail telling me the FBI doesn’t have any records for former baseball manager Sparky Anderson. But I figure there’s even comedy in the fact that somebody at the FBI had to ask around about Sparky Anderson.

How do you incorporate these documents into a show?

My opening monologue explains what FOIA is, since I don’t expect most people to know that coming in. I use celebrity FBI files to explain the law and what types of documents are public, since I figure people could relate to a document about someone they’ve heard of. So I put up Steve Jobs’s FBI file on the projector during the monologue, then kept projecting documents throughout the show.

After the monologue, I really get out of the way and let the documents do the work. This show would fail if it was just me standing onstage telling people what documents said, so I wrote some sketches with an early Conan [O’Brien] feel. For some, like the Fred Davis trial, all we had to do was repeat the words in the document. We didn’t write anything, but just read portions of his testimony verbatim. Since Fred Davis and the plaintiff both represented themselves in that case, there’s plenty there to laugh at.

The first half of the show is heavily researched, while the second half is all improvised off of the PACER court records database. We asked the audience to give us a last name, and someone shouted out “Dempsey.” So we searched through a couple of criminal complaints from defendants named Dempsey and improvised scenes based on those premises.

What sort of things did you come up with?

Everything from sophisticated premises to dumb ones. In one of the cases, the defendant was accused of dealing a class of narcotics called methaqualone. Since none of us had heard of this type of drug, and “methaqualone” sort of sounds like a last name, we did a scene about an Italian family named the Methaqualones. The unnecessary complexity of legal jargon also emerged as a strong theme, like sentencing people to “75 months” in prison. It’s hard to ignore the absurd way lawyers and judges write, or how many ways they come up with to say “drunk driving.”

Have you learned anything about FOIA in developing this show?

I sent in five requests to the FBI, and none of them got responses in time for the show. So I’ve learned to be more patient, to budget more processing time, and to submit to another agency if another drags its feet. You also have to see what’s already been requested and released rather than going out submitting requests blindly. Once I found one threatening letter or copy of a form, I know there’s probably a lot of similar documents out there.

What’s the future look like for “FOIA Love”?

I’m aiming to be back in January and launch it as a monthly show. There’s so much information out there, and the response was so strong this first time around, that I’m energized to do it again. The reception on the Twitter #FOIA hashtag has been even bigger, which I should have seen coming. Public records are hilarious, mostly because all the stories are true. This stuff really happened, and someone had to write it all down.

Image via CurtisRaye.com