On the afternoon of 1 Oct. 2002, a resident of Back of the Hill Apartments in Jamaica Plain called a federal low-income housing hotline to report unacceptable conditions in the complex.

“Caller has a complaint that there has not been an exterminator in the building in nine months,” the hotline operator jotted down in the complaint log. The tenant reported that roaches, mice and other bugs were in the development.

The Back of the Hill apartment complex contains just 125 of the more than 26,000 public and subsidized housing units in Boston. All together, they house 58,000 residents across the city. Built in 1980 with federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funding as a Section 8 community for the elderly and disabled, Back of the Hill received an extensive overhaul in 2008 with $11.8 million in loans from the Massachusetts Housing Finance Agency to address “dire rehabilitation needs.”

Have any Back of the Hill residents called the HUD hotline more recently to report unsafe or unsanitary conditions? Fourteen months after posing that same question to HUD, I still have no answer.

Several pages on the HUD website point to one particular hotline number as the appropriate tool for reporting a bad landlord for a range of misdeeds, including “poor maintenance, dangers to health and safety, mismanagement and fraud.” I was interested in getting a rough sense for how often Boston’s public and subsidized housing tenants find themselves living in unacceptable conditions. The HUD hotline seemed a good place to start.

And so it was that I submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to HUD in June 2013. Little did I know that this single FOIA request would reveal so much more about HUD’s administrative capacity than it did about the state of low-income housing in Boston.

I filed my request on 5 June 2013 for all complaints submitted to the HUD tenant hotline over the past 10 years. After more than a month without response and then another month of touch-and-go communications with a HUD records clerk, on 23 Aug. 2013 I received a brief table that summarized hotline complaints back to 2003.

A total of 46,149 calls came in to the HUD hotline between Jan. 2003 and June 2013, the table indicated, including more than 18,000 complaints for maintenance issues.

These summary figures are fascinating, but I did not request a table. Rather, I requested the content of the hotline complaints themselves. Having reviewed similar complaint logs from the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Trade Commission, I know that all complaints are not created equal. To get a true sense for the grievances and their severity, one has to read them all.

After reiterating in a number of calls to HUD’s FOIA and data staff that I was after the hotline logs rather a summary, I waited patiently another two months … and another three months … and then two more.

Finally, on May 30 – a week shy of my request’s one-year anniversary – a package arrived. While I had expected HUD to send data by CD, the thick envelope contained more than 100 pages of printouts. As I dove into the documents, I was initially excited to see that HUD had generously included complaints back to Aug. 2002.

Scanning quickly, I saw that a tenant from Harbor Apartments in Milford called on 20 Aug. 2002 to report unresolved maintenance issues going back 10 years. Six days later, another tenant in Brookline reported a landlord for refusing to fix up an apartment. The log recorded similar complaints for general maintenance, sewer issues and lack of heat from Rockland on September 13, from Worcester on Oct. 2 and from East Hampton on Oct. 15.

Every 10 pages or so, there was a call from a Massachusetts tenant – including one report of sexual harassment in East Boston from 26 Sep. 2002 and the pest infestation complaint above.

I flipped to the end of the packet to review more recent complaints. but the final log entry was dated 13 Jan. 2003. After a year of delay, HUD had released five months worth of data, the most recent of which was more than 11 years old.

HUD included no hints as to why its staff had released such a narrow and outdated selection of its complaint database. The packet’s cover letter itself referred to complaints “for the past 10 years.” My saga to liberate basic documentation on affordable housing oversight continued.

Several calls, emails, litigation threats and stern letters later, HUD finally agreed in August to release 3,967 pages of hotline complaint logs in batches over the coming months. It has not provided any timeline for completing this task.

Quality of life within public and subsidized housing is no idle matter. Housing authorities coast to coast are grappling with aging facilities and looming budget cuts, and some are failing in their duty to protect resident health and safety. More than ever, the national low-income housing system requires transparency and accountability to prevent abuse and negligence, as well as bring past violations to light.

In the past year of HUD foot dragging on the hotline documents, public housing officials in Richmond, Calif. have come under particular criticism for chronic maintenance failures. An in-depth series from the Center for Investigative Reporting published in February uncovered pest infestation, falsified maintenance reports and evidence of financial mismanagement by Richmond Housing Authority (RHA) administrators. For years, HUD has categorized Richmond as a “troubled” housing authority. In the wake of CIR reporting, it even threatened to assume responsibility for RHA properties.

The Community Service Society of New York released a report earlier this summer that identified an uptick in maintenance deficiencies in New York City Housing Authority developments, as well. The report suggested that budget shortfalls have wrought considerable damage to the country’s largest public housing authority over the past decade. “A well-wrought preservation plan is needed to restore NYCHA communities to decent condition,” it concluded.

Boston public housing also has a checkered history when it comes to living conditions in its developments. In July 1979, a judge found that the BHA board had failed to remedy widespread violations of residents’ rights to decent, safe and sanitary housing. The judge places the city’s low-income housing system in a court-appointed receivership for the next eleven years, at which point another judge found that conditions had sufficiently improved.

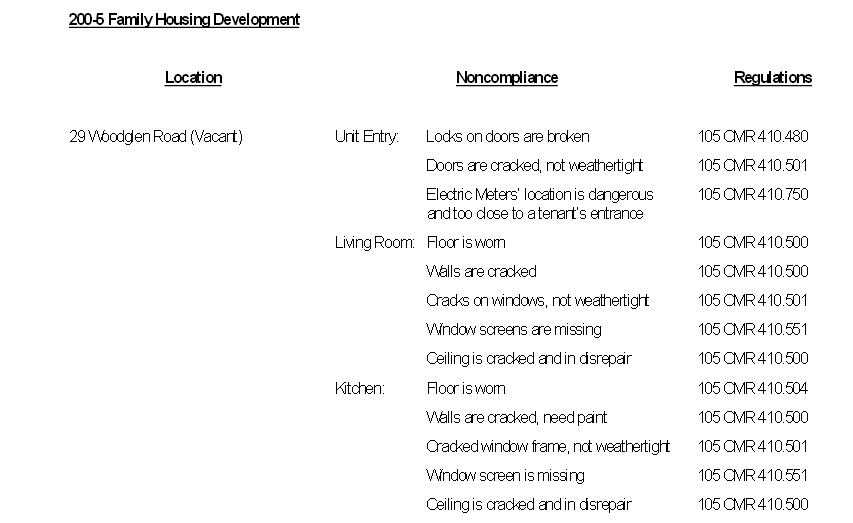

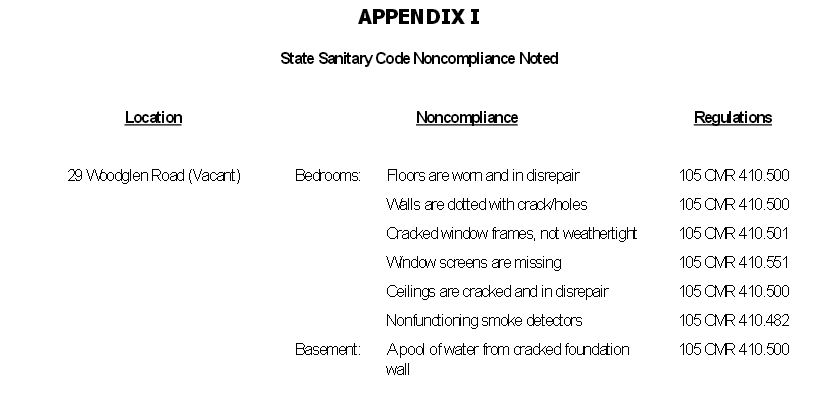

Even as recently as 2008, Massachusetts state auditors warned that conditions in certain BHA units failed to meet state health and sanitation codes. In walk-through inspections of nine units, auditors tallied more than 200 violations from ceiling mold and broken smoke detectors to missing locks and rotten wood beams. A followup report in January 2011 found that BHA remedied virtually all specific violations.

However, many problems still persist. For example a grand jury indicted the former executive director of the Chelsea Housing Authority and two other person last year for rigging health and sanitation inspections. Prosecutors accuse Michael McLaughlin, James Fitzpatrick and Bernard Morosco of colluding with contracted inspectors to selectively repair units chosen for walk-through assessments.

Many public housing advocates in Boston say that the city’s maintenance oversight has improved considerably in recent years. However, they also believe that vigilance is key to maintaining high standards.

“I find that, for the most part, BHA wants to deal with things immediately,” said Mae Fripp, executive director of the Boston Committee for Public Housing. According to Fripp, collaboration among BHA, the Boston Public Health Commission and local universities has been key to improving maintenance issues.

Fripp grew up in Boston public housing and remembers when developments such as Orchard Park in Roxbury were dangerous to the point that cabs and postal workers steered clear.

In addition to strong funding from HUD, university initiatives and foundations, Fripp credited communication between residents and BHA officials – including the installation of a multi-lingual maintenance help line and strong advocacy from tenant groups – for bringing BHA to a place where maintenance is not a central issue.

“I’ve seen this community go from having good maintenance to poor maintenance and back to good maintenance again,” said Fripp, summarizing her years of living in public housing and organizing public-housing tenants. “It’s been a long haul to get the housing authority where it is, with organizations and residents working together.”

BHA officials credited a combination of annual inspections and tenant work orders with staying on top of maintenance issues. But they also emphasized that their aging portfolio of buildings means that there will always be upkeep to do and that budget limitations mean they must defer some work.

“In general, we do a pretty good job of getting work done in a timely way,” Gail Livingston, BHA’s deputy administrator for housing programs, said of the system’s handling of maintenance issues as they arise. Livingston added that tenants ought to be assertive in bringing forward any maintenance issues they find.

“A small leak can quickly become a big leak,” she explained.

Earlier this year, HUD awarded BHA $18.5 million for capital improvements and property renovations. As Boston works toward improved quality of life for all of its residents, transparency and accountability will be key to ensuring public funds are used responsibly.

I will continue to investigate the state of low-income housing in Greater Boston for MuckRock and Spare Change News over the coming months, publishing key documents along the way – if, that is, HUD ever hands them over.

This article is part of a joint investigation of low-income housing conditions in Greater Boston by MuckRock and Spare Change News, funded in part by a generous grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Image via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0