Last week, in collaboration with The Marshall Project, we did the first breakdown of the Pentagon’s agency-by-agency data for its 1033 program. It’s taken a lot of persistence to get such granular data, and our work around tactical equipment transfers to police is testament to how effective stubborn insistence on transparency can be.

Created in 1989, the 1033 program transfers excess military equipment to thousands of participating law enforcement agencies across the country, including local police and sheriffs departments, state public safety forces, and several federal agencies. The program has doled out $5 billion in equipment since 1990.

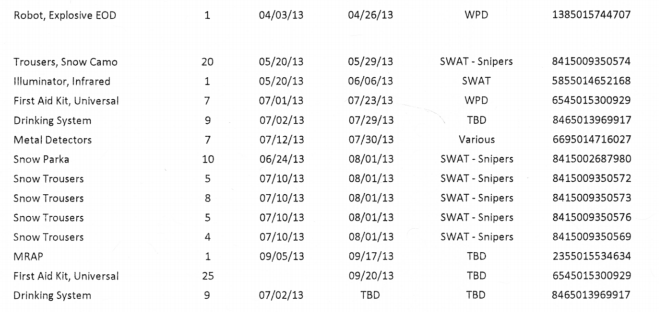

MuckRock has been investigating the 1033 program since October 2013, when MuckRock user Robert Ritchie’s request to police in Madison, Wisconsin uncovered that the department had received one mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicle (MRAP) the previous month, as well as a bomb robot in April 2013.

Our interest piqued, we submitted requests to the Defense Logistics Agency, which oversees the 1033 program, for a roster of all participating agencies nationwide as well as for a database of all tactical equipment distributed.

While the DLA was willing to release its full agency roster, its FOIA staff insisted that equipment allocation data could be released only down to the state level. Spreadsheets released in December 2013 listed each individual weapon, armored vehicle and aircraft allocated, but only the state for the recipient agency. (Oddly, the DLA released data down to the county level in May 2014 in response to a request submitted by reporters from The New York Times.)

Then Ferguson happened.

Stirred by images of police in military gear and armored vehicles marching toward protesters, MuckRock submitted requests under each state’s public records law to each of the 50 state coordinators of the 1033 program. Within three weeks, more than half the states released spreadsheets detailing 1033 program equipment transfers down to the individual agency level.

By early November, only 12 states either refused to release this level of data or (dubiously) responded that such spreadsheets could not be accessed. Louisiana, in a category of refusal unto itself, insisted that this information was available upon payment of $5,000.

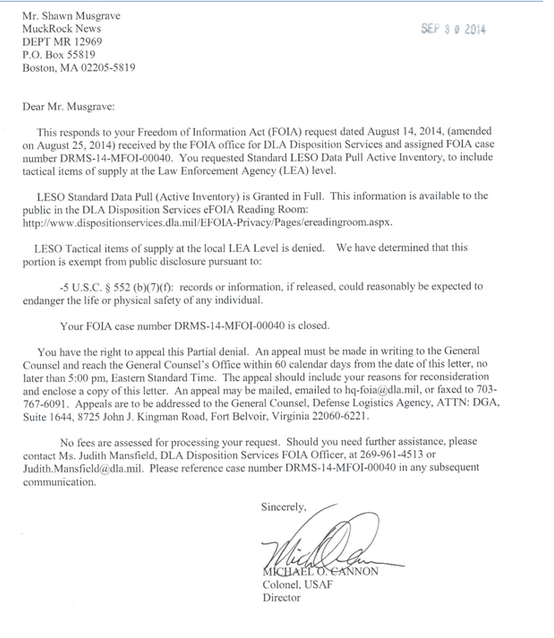

Despite widespread agreement among state coordinators, the Defense Logistics Agency held the line on withholding agency-level data for equipment transfers. In a September 30 letter, the DLA claimed that such information, “if released, could reasonably be expected to endanger the life or physical safety of any individual.”

MuckRock appealed this determination on November 21.

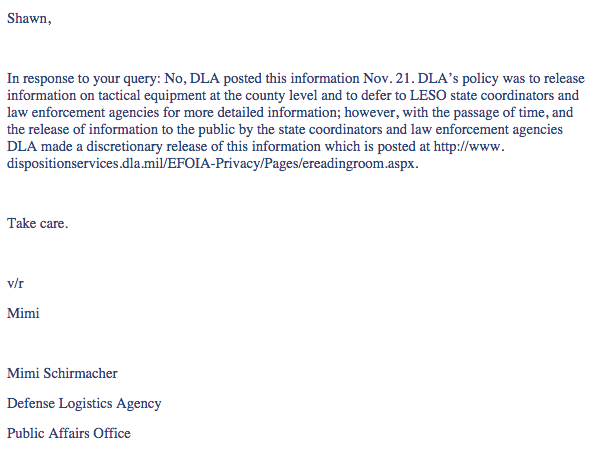

The very same day, with no formal public announcement, the DLA posted online two comprehensive spreadsheets with agency-level data for tactical equipment transferred via the 1033 program, current up to November 14. The spreadsheets were placed on the DLA FOIA reading room under identical hyperlinks that previously contained spreadsheets with only county-level detail, which were posted in late August.

The DLA did not advise MuckRock of this about-face in policy as to 1033 program data, even upon receipt of our FOIA rejection appeal.

MuckRock only learned that such data had been posted following last Monday’s release of White House findings that the 1033 program lacks transparency and community accountability. When we passed such a call for greater transparency to the 13 laggard states, two responded that a complete inventory list was already available.

“FYI: The DLA released a complete inventory list for every state,” answered Captain Michael Corsaro, deputy chief of staff for the West Virginia State Police.

“The information you are requesting is readily available through the DLA Website,” echoed Corinne Geller, public relations director for the Virginia State Police.

And so it was that MuckRock visited the DLA reading room, downloaded the inconspicuous spreadsheets, which at last revealed which particular police departments nationwide scored anti-personnel mine foot protection.

The DLA acknowledged that the efforts to pry this data from state coordinators spurred release of this critical information.

Asked whether the White House review catalyzed the disclosure, a DLA spokesperson responded in the negative. Instead, she credited the “discretionary release” to “the passage of time, and the release of information to the public by the state coordinators and law enforcement agencies.”

Translation: by going after each state’s data, MuckRock and fellow transparency advocates sprang the spreadsheets for the entire country.

By taming the logistical bronco that is haggling with 50 separate agencies in 50 separate states for snippets of a larger picture, we prodded the program’s federal administrators to release the entire frame.

How do you eat the elephant of government transparency? One hard-won bite at a time.

Image via Wikimedia Commons