Newly disclosed documents reveal FBI field offices around the country took measures to prepare for an anticipated visit by legendary Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap in 1993. But, for reasons that remain unclear, the potentially historic trip never came to pass, despite what FBI informants initially reported.

Dubbed “The Red Napoleon” by admirers, General Giap died in October 2013 at age 102. He is widely numbered among the great military strategists of the 20th century, having repelled both American and French forces after decades of brutal warfare. Giap later served as defense minister and deputy prime minister of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

But by 1993, the newly retired firebrand had become an outspoken supporter of his country’s reconciliation with the United States, and was considering a goodwill trip—that is, depending who you believe.

In a teletyped memorandum to FBI headquarters and various field offices in January 1993, agents in Minneapolis reported information from a “reliable” asset that the controversial general had plans to visit the United States.

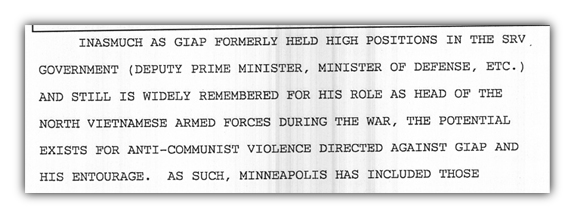

“Inasmuch as Giap formerly held high positions in the [Socialist Republic of Vietnam] government (deputy prime minister, minister of defense, etc.) and still is widely remembered for his role as head of the North Vietnamese Armed Forces during the war,” the agent wrote, “the potential exists for anti-communist violence directed against Giap and his entourage.”

“… All offices are requested to contact logical sources in an effort to develop information concerning any possible threats directed against Giap during his visit to this country.”

The fears were not unfounded. There had been several assassinations of Vietnamese-American journalists in the 1980s, purportedly carried out by the “Vietnamese Party to Exterminate the Communists and Restore the Nation” (VOECRN). Other groups organized armed militias aimed at kindling violent resistance on Vietnamese soil.

On top of that, Giap was a widely recognized icon of a nearly universally reviled regime among the émigré population. One asset told agents to expect “widespread protest” should Giap arrive on American soil, which he speculated would only be avoided if the communist leader was brought into the states “unannounced and in disguise.”

But, as field offices responded with their findings, all reported their sources to be unaware of any impending visit by general.

“Contact with…credible and reliable sources in a position to know, failed to develop any verifiable information,” the Milwaukee field office reported. “In fact, neither asset was aware of Giap’s pending visit.”

New York, Sacramento, Baltimore, Portland and San Diego field offices all reported similar findings.

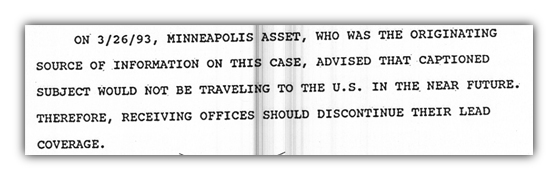

Then, two months after their initial report, Minneapolis sent out a followup memo on March 26, 1993:

“Minneapolis asset, who was the originating source of information on this case, advised that [Giap] would not be traveling to the US in the near future,” it reads. “Therefore, receiving offices should discontinue their lead coverage.”

No further explanation is clear in the available documents, though more than half the pages relevant to the FOIA request - including a referenced “tentative itinerary” - were redacted, with the Bureau citing the need to protect confidential informants.

The release of these documents seem to raise more questions than they answer. Was the source in Minneapolis mistaken, or even misleading investigators? Were they telling the truth? If the initial reports were true, what changed Giap’s mind or blocked his travel plans?

What locations were listed on the “tentative itinerary” obtained by the FBI? What other clarifying details were omitted in the Bureau’s redactions?

One Californian asset advised that Giap was under “house arrest,” though this was incorrect, according to Clemson University History professor Edwin Moise.

Another clue embedded in the files: the special agent in charge of the Baltimore field office advised that “follow-on trip to the US is uncertain,” suggesting perhaps a scheduling issue for a multi-nation trip.

However, the rest of the paragraph is redacted.

No press accounts from the period indicate Giap was considering a trip to the United States, though Professor Moise said there “would have been nothing surprising” about such plans.

“Certainly he was interested in talking with Americans about the Vietnam War,” he said.

Indeed, Giap met with a number of American officials in the 1990s, including unlikely face time with former Sec. of Defense Robert McNamara and Sen. John McCain. Neither meeting took place on American soil.

Giap’s file is scheduled for full declassification in early 2039. Until then, the heavily redacted documents provide an interesting historical ‘what-if’ for observers of Vietnamese-American relations: Would a visit from American’s once-nemesis have helped or hurt both nations’ strides toward reconciliation?

Image via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0