In the mid 1970s, the FBI took an interest in Harvard Law School professor and famed negotiator Roger D. Fisher. Agents hoped to convince Fisher to gather information on an acquaintance of his, a Soviet diplomat the Bureau believed to be a KGB spy. Unable to uncover any dirt on the professor, agents decided they didn’t have enough leverage to bring Fisher to the table.

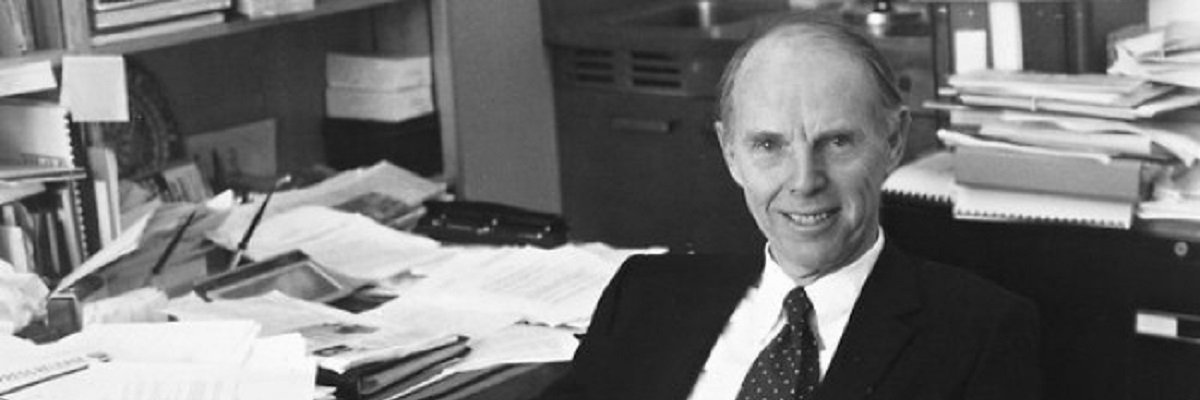

Author of the seminal and best-selling manual “Getting to YES,” Fisher was a professor at Harvard Law for more than four decades, and focused his career on honing negotiation and conflict resolution techniques. Professor Fisher contributed to international negotiations from the Marshall Plan to the Iranian hostage crisis, and co-founded the Harvard Negotiation Project in 1979. He died in August 2012.

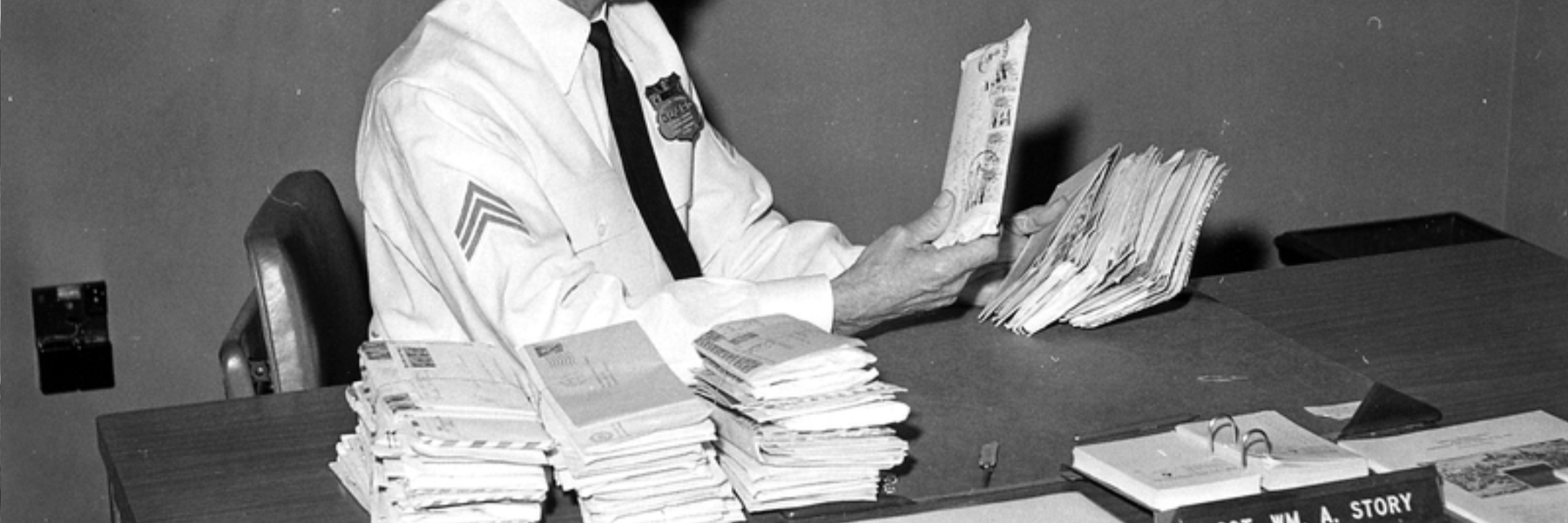

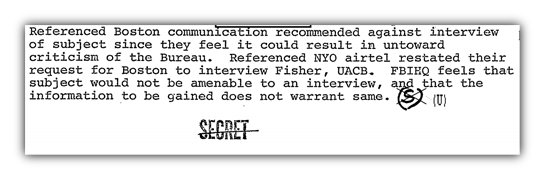

According to his FBI file, the FBI’s New York office first pressed their Boston peers to gather information on Fisher in 1973. Their aim was to assess Fisher’s personality and interview him with an eye to his “asset potential” as an informant. But Boston FBI agents pushed back, citing concerns that an unsuccessful attempt to recruit the Middle East expert would prove embarrassing and result in “untoward criticism” of the Bureau.

New York agents kept pressing for an interview with Fisher. “Notwithstanding Fisher’s altruistic and academic intentions, he may nonetheless be vulnerable” to corruption by the Soviet spy/diplomat in question, a New York agent wrote.

The suspect diplomat’s name is redacted throughout the documents, but agents wrote that he was a member of the Soviet Union’s delegation to the United Nations, as well as an “an adroit, experienced KGB officer of the Political Branch.” He and Fisher had met only once and communicated sparingly, if at all, the FBI believed.

After conducting a background investigation on Fisher, Boston agents had uncovered “no substantial derogatory information.” He had been a delegate of the American Youth Conference, a group the FBI watched, and his father had belonged to several organizations with communist connections. But agents found no evidence that he had been courted by the Soviets or that he had communist sympathies.

In April 1976, word came down from FBI headquarters that the Harvard professor was not to be contacted because he did “not appear to be the type of individual who would be amenable to an interview by this bureau concerning his contact with Soviet officials.”

Without any leverage, the FBI decided not to even bring Fisher to the table.

Image via Harvard University