A version of this article originally appeared on Motherboard

While it might seem unlikely that Bob Belcher, the eponymous lovable loser voiced by H. Jon Benjamin on FOX’s Bob’s Burgers, would have much advice to lend federal law enforcement, audit findings released last week by the Justice Department’s inspector general suggest otherwise — at least when it comes to drones and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

In particular, Bob’s commitment to getting his money’s worth seems a fitting model for ATF and like-minded agencies eager to test the waters of unmanned flight.

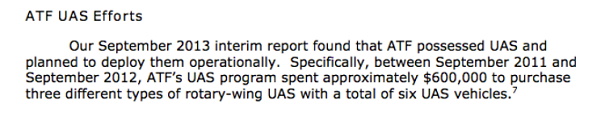

Let’s start at the top: Last week’s report surveyed the Justice Department’s drone usage, and mostly focused on the FBI, which is the only bureau in the DOJ to have carried out drone flights. But also in the report was the admission by ATF that it had spent $600,000 on drones that it never flew—because they were faulty, the ATF claims.

What does this have to do with a sad sack cartoon chef? The world recently learned of Bob’s doomed affinity for remote-control helicopters, and especially ones that come with their own dangling figurine of Jamie Lee Curtis. Bob’s wife, Linda, chastises the less-than-sober purchase, which he insists was the result of “nighttime shopping with wine” rather than “drunk shopping.”

In similar fashion, Justice Department auditors questioned the utility of the ATF’s drone purchases. The ATF bought six rotary-wing drones between September 2011 and September 2012, auditors report, at a total cost of approximately $600,000. According to the report, those drones never once flew actual missions. (Bob, meanwhile, paid $45, “plus shipping… which was also $45.”)

In stark contrast to Mr. Belcher’s eagerness to show off his new toy, the ATF declined to indicate which particular models it purchased, both in the report and in follow-up queries from MuckRock. But Bob and the agency do share a common frustration with “technological limitations” once their drones are out of the box.

In Bob’s case, a short but disastrous first flight leaves his copter in shards just minutes after it’s unwrapped.

“This thing is a piece of crap,” Bob concludes, cradling his shattered hopes. “I’m getting my money back.”

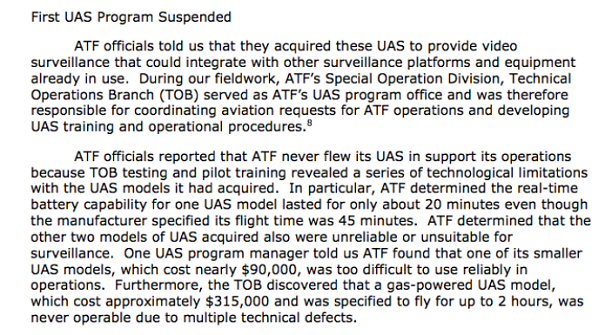

The ATF likewise encountered a quick succession of hiccups across three drone models its Technical Operations Branch purchased for video surveillance.

One drone model purchased by ATF — a gas-powered drone with a sticker price of approximately $315,000 — never worked at all, agents told inspectors, due to “multiple technical defects.”

The battery life on a second model was less than half that advertised by its manufacturer. User-interface roadblocks rendered a $90,000 third model “too difficult to use reliably in operations.”

Both Bob and ATF, then, find their first drone dances to be disappointing. But while Bob refuses to drop the issue, the ATF didn’t even ask for its money back.

First by email, then by phone, and finally in face-to-face confrontation, Bob demands a full refund. He persists even when chased into a dumpster by a poke-happy quadcopter.

“I’ve got rightness on my side,” Bob explains to his son.

ATF’s total outlay on defective drones was several orders of magnitude greater than Bob’s, and its purchases made using public funds. Unlike Bob, though, the agency did not request a refund when its pricey equipment failed to measure up.

Last summer, after finding all three drone models “unsuitable,” the ATF shuttered its drone program. In September, the agency transferred all drones and related equipment to the Naval Criminal Investigative Service at no cost. An NCIS spokesperson declined to provide additional details of this lateral handoff beyond indicating that “the units are non-functioning and are early technology.”

“NCIS intends to cannibalize the UASs for spare parts,” the spokesman said by email, “specifically for camera gear.”

Granted, ATF has an annual budget comfortably above $1 billion, so $600,000 hardly registers a blip. Still, auditors report that they are “troubled” at the agency’s purchasing drones that were “subsequently determined to have mechanical and technical problems significant enough to render them unsuitable for deployment.”

The agency also failed to indicate whether it conducted any test flights ahead of its drone purchases.

Here, too, ATF might look to Bob for guidance: Having been burned once, Mr. Belcher visits a reputable shop in-person to purchase another model. Bob is sure to try out the merchandise before leaving.

“Huh, it’s actually pretty intuitive,” he says after a hands-on tutorial.

ATF officials did not respond to emailed questions as to whether its staff conducted similar vetting before signing checks for drone equipment.

The inspector general’s report did identify one last snag where Bob may not have been able to guide the ATF. Less than a week after headquarters disbanded its drone program, another ATF team purchased five off-the-shelf drones for $15,000.

Bob Belcher is many things, but a skilled communicator he is not. Auditors likewise criticized ATF for failing to communicate the drone program’s suspension throughout the agency.

The National Response Team flew one mission with its three-pound drones to document the scene of an apartment fire in July 2014 before being informed that the entire project was in violation of Federal Aviation Administration requirements. It remains unclear whether the NRT has since obtained FAA approval, or whether the team will seek case-by-case emergency authorization.

MuckRock has filed a number of Freedom of Information Act requests regarding ATF’s past and future drone deployments.

Because, as Bob indignantly shouts, “It’s the principle.”

Image via Bob’s Burgers on Fox