A version of this article appeared on Motherboard

Ahead of the Boston Marathon on Monday, city officials were adamant: no drones along the route. Such a ban isn’t unprecedented, but the plan for keeping drones out of marathoners’ faces highlights the difficulty of spotting the damn things, much less taking them out. Naturally, the plan flirted with net guns.

“The entire route of the Boston Marathon will be a ‘No Drone Zone,’” declared the caps lock-happy spectator guidelines issued a week before the race. “The public is being advised NOT to operate any type of drone (unmanned aerial vehicle), including remotely controlled model aircraft, over or near the course, or anywhere within sight of runners or spectators.”

It was less obvious how such an order could be enforced. Thousands of people flood into Boston and the surrounding suburbs on race day, many of them photographers eager to get shots of the runners and spectators. Initially, there were few details as to what steps police planned to take if they spotted a quadcopter or other drone hovering over the massive crowds.

So when Brian Hearing learned about the drone ban, he called Boston police brass and offered his services.

As founder of DroneShield, a company based in Washington, DC that designs drone detection systems, Hearing knew just how difficult it is to locate drones at large spectator events, much less to eliminate them.

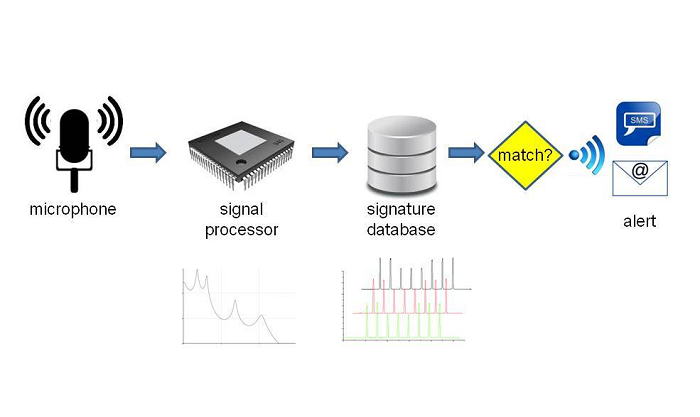

The DroneShield system compares sounds within range of its omnidirectional microphone to acoustic signatures for common consumer drones. If it detects a match, DroneShield sends an alert by text or email.

Image courtesy DroneShield

Image courtesy DroneShield

Unlike many other cities, Hearing said, officials at BPD were eager to try the system, and asked his team to come up for the race. At a Friday press conference, Boston Police Commissioner Bill Evans confirmed that his department would deploy “anti-drone technology” but did not elaborate beyond indicating that there would be sensors “in several locations along the route.”

Yes it's us: DroneShield to help Boston Marathon detect unauthorized drones— DroneShield (@DroneShield) April 17, 2015

“It happened so quickly,” says Hearing. “We threw everything in a van and set up on Sunday night.”

The company has sold systems to celebrity clients wary of drone-savvy paparazzi or stalkers, to prisons seeking to prevent security breaches, and to sports stadiums worried about unauthorized filming. But DroneShield has never deployed for an event on the scale of the Boston Marathon.

The ten DroneShield sensors installed on lampposts along the 26.2-mile race route detected no drones throughout the day. While that’s somewhat a disappointment from an engineer’s perspective, Hearing said, his team learned from the unique acoustic challenges posed by spectators.

“Once the cowbells showed up, we had to worry about that,” he said.

Hearing said that the quick installation meant his team wasn’t able to calibrate as much for background noise as he would have liked. Depending on the site, his systems have to account for machinery, sirens, leaf blowers, lawn mowers or tailgating music. But cowbells were a first, and he is proud that the system had no false alarms throughout the event.

Teardown time.. Great success! Thank you Boston Marathon and BPD @bostonmarathon @bostonpolice pic.twitter.com/kLwCaInLu5— DroneShield (@DroneShield) April 20, 2015

DroneShield and similar systems are all about deterrence by way of detection, which has become increasingly difficult as drones continue to shrink. The radar-based system that monitors White House airspace, for instance, was not sensitive enough to pick up the quadcopter that crashed on the president’s lawn in January.

Hearing acknowledges the difficulties, both legal and practical, around dealing with an unwelcome drone. It’s among the most frequent questions posed at demonstrations of his system.

“Unfortunately, there’s not much a private citizen can do,” Hearing answers. “The airspace above your backyard is public, so you have no expectation of privacy there.”

Hearing elaborates that anyone who tries to shoot down a drone might be charged with a range of crimes, including reckless endangerment or even tampering with an aircraft.

For celebrity, politician, or other VIP clients, Hearing said the aim of installing DroneShield is to be alerted of an approaching drone in time to go inside, close the drapes and call the police.

“Nine times out of ten, when a cop asks you to take down your drone, you will,” Hearing notes. In the US, it is also illegal to fly a drone within 5 miles of an airport or heliport without air traffic authorization, a fact which DroneShield’s customers also rely on for deterrence.

Law enforcement officers have a wider range of options for taking down a drone, whether at public events such as the Boston Marathon or when responding to complaints of aerial stalking. For police, the issue is more practical than legal.

Much was made of DroneShield’s offer to arm BPD with net guns in case of a detected drone at the marathon.

BPD declined to carry the net guns, and Hearing emphasizes that they are far from an ideal solution. But when law enforcement believe that a drone threatens public safety, they need tools to neutralize such a threat. They must also weigh the danger posed by the drone itself versus the danger in bringing it down, particularly over populated areas or crowds.

Hearing theorized that police might use beanbag or pellet guns to take down a drone, or live ammunition in particularly dire circumstances. Other suggestions which Hearing has explored range from fire hoses to trained falcons.

“You’d have to find a pretty unethical bird owner,” he mused.

Jamming is an option for local forces. Only the FBI, Secret Service or another federal agency could legally jam the signal between a drone and its operator, or jam its GPS connection if the drone’s flight pattern is preprogrammed.

In short, as with planes and automobiles, dealing with rogue bodies remains an unsolved matter. But Hearing insists that the issue isn’t going away, that drones will only get more common around the world, and that we need systems to detect them in places where they shouldn’t be flying.

As a new company, DroneShield hasn’t faced much inquiry from privacy advocates in the way that other microphone-based detection systems have. ShotSpotter, for instance, which alerts law enforcement to nearby gunshots, has been criticized by those concerned about the Fourth Amendment implications of its massive deployment and retention of recordings in raw, intelligible form.

In its current design, DroneShield poses minimal privacy threat, Hearing says. Upon sampling sounds within range, the system converts them into spectrum format for filtering and comparison to a database of drone sounds. He says that no raw recordings are retained, and that this sound data conversion could not be reversed.

Hearing hopes to return to Boston for the 2016 marathon, and DroneShield is currently in talks with marathon organizers in Chicago and New York. The Boston Police Department did not answer our request for comment as to factoring drones into security strategy for such events, but we have submitted a records request to the department for documents related to its deployment of the DroneShield system.

Image by Gr5555 via WikiMedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0