Every year, a certain number of bees die. And every year, a certain number of people die while in police custody. We have a solid figure for one of these death tolls.

At present, it’s not the human body count.

As with deaths in custody, the issue of honeybee deaths is not new. Colony collapse disorder — the generic term for mass exodus of adult worker bees from a given colony — is nearly vernacular, and wonks routinely debate the scale of the problem and its long-term consequences.

Such debates hinge on quantitative modeling, on forecasts that correlate honeybee population against crop yields or ecosystem resilience. Ask any beekeeper: the only way to know how many bees are around is to count them.

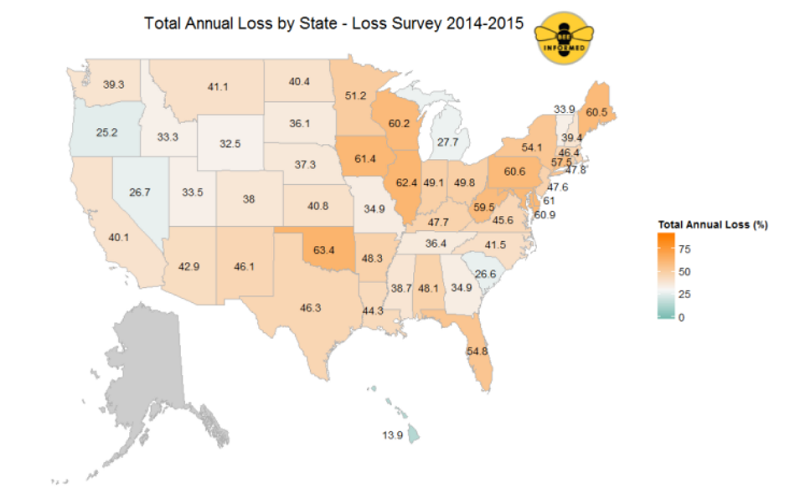

So we do. Agricultural statisticians routinely assess honeybee populations using viable, peer-reviewed survey methods. There’s the Bee Informed Partnership, for instance, a research initiative funded by the United States Department of Agriculture and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Since 2006, the Bee Informed Partnership has conducted an annual survey of bee colonies nationwide.

Preliminary results from the most recent survey highlighted Illinois and Oklahoma as having particularly high drops in bee colony populations. Beekeepers reported that total losses across the country were lower than for the 2013-2014 winter. Finalized results for the previous year’s surveyed were published in the scientific journal Apidologie following a peer review process.

“Long-term data on losses are critical for putting yearly losses in context,” declares the Apidologie abstract. To get a useful picture of an issue, you need to know its scale and chronological trends.

In May, the White House Pollinator Health Task Force called for more frequent surveys to quantify and map colony losses. But when it comes to bees, there’s a robust baseline from years of granular data collection.

Police reform also has its own White House task force. The May 2015 final report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing emphasized just how inadequate our data is to answer how many deaths occur within the criminal justice system, much less to discern regional trends or policy implications.

All law enforcement agencies should “collect, maintain, and report data to the federal government on all officer-involved shootings, whether fatal or nonfatal, as well as any in-custody death,” the report recommends. The damning implication is that far too many police do not track these figures.

To date, all attempts by the federal government to count how many people die each year while interacting with law enforcement have relied on voluntary reporting. Whether a person dies during a pursuit or while in handcuffs, whether the death is accidental or intentional, the details find their way to nationwide databases only if a particular police or sheriff office decides to submit them up the reporting chain.

This is woefully inadequate, and the White House task force called for the federal government to move beyond voluntary reporting as the centerpiece of its data collection strategy. The statisticians charged with tracking nationwide law enforcement trends agree that we need to take a page from the bee-counters.

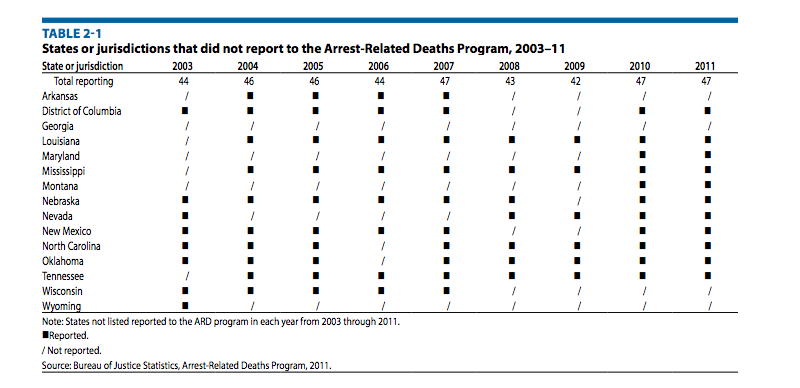

The Bureau of Justice Statistics launched its Arrest-Related Deaths program in 2003. The ARD program aspires to be a “national census of persons who died either during the process of arrest or while in the custody of state or local law enforcement personnel.”

But the ARD was based on the voluntary, decentralized reporting model, and participation varied widely from one state to another. Some states like Georgia, Maryland, Montana and Wyoming declined to contribute to the ARD database for years at a time. Other states identified cases only passively. Far from being a comprehensive census, the ARD program was significantly undercounting deaths in the criminal justice system.

But the ARD was based on the voluntary, decentralized reporting model, and participation varied widely from one state to another. Some states like Georgia, Maryland, Montana and Wyoming declined to contribute to the ARD database for years at a time. Other states identified cases only passively. Far from being a comprehensive census, the ARD program was significantly undercounting deaths in the criminal justice system.

The federal ARD program was thus suspended in March 2014. In an evaluation released a year later, the Bureau of Justice Statistics concluded that the ARD program “captured, at best, 49% of all law enforcement homicides in the United States.” Other estimates put the program’s coverage as low as 36 percent.

“If BJS pursues a collection to measure law enforcement homicides or all manners of arrest-related deaths in the United States, changes must be made to the data collection methodology to support more complete coverage,” the evaluation summarized.

Dr. Michael Planty, chief of the Victimization Statistics Unit at BJS, could not agree more. If policymakers, advocates and police officials want to understand the factors that lead to fatal police encounters, Planty says, they need comprehensive data as to where those deaths are happening.

“Law enforcement is often thought of as a localized issue,” Planty elaborates, “but it’s become apparent to most people that a death in one jurisdiction affects all law enforcement across the country. We need to see this as a national issue.”

National issues require national data, and exhaustive coverage. To that end, the BJS is piloting a more aggressive methodology. Rather than rely on agencies to report fatal events on an ad hoc basis, the ARD team itself combs for cases, then confirms details of a given individual’s death with the respective law enforcement agency and coroner.

Since June, the ARD program staff have been using open sources — such as news reports and police department websites — to identify individuals who died in the course of an arrest. Other database projects at Fatal Encounters, the Washington Post, the Guardian, and Deadspin likewise depend on open sources as their primary leads. Such a proactive approach demands more time to collect each case, and the BJS may retain a contractor as it does with many of its programs.

Federal statisticians will assess the new ARD program this fall by surveying state and local law enforcement agencies to determine how many cases the proactive search method missed. The BJS will refine its approach based on the results, and Planty hopes to have a more robust, systematic methodology on its feet by next year.

The clock is ticking, and not just because of the glaring need to have comprehensive figures on this issue. President Obama signed the Deaths in Custody Reporting Act in December 2014, which ties federal law enforcement grants to states’ reporting of comprehensive information about deaths in custody. The revamped ARD program will be the mechanism for such reporting.

MuckRock will continue to follow the overhaul of the Arrest-Related Deaths census through its pilot assessment this fall and nationwide rollout next year. We have requested documents on the suspension of the program last year, as well as the pilot.

Police chiefs and civil rights advocates agree that rigorous and timely statistics are critical to reforming police practice nationwide. As with honeybee populations or extinctions or financial mismanagement or ebola or deteriorating infrastructure, informed analysis demands sound data. How many people are dying in police custody? Start counting.

Image by Björn Appel via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0