Cesar Estrada Chavez, Mexican American icon and prominent leader of an historic strike of California farm workers, was the subject of hundreds of pages of FBI correspondence throughout the ’60s, speculating on the nature of his humanitarian and civil rights activism - much of which seems to suggest skepticism in regard to the sincerity of Chavez’s intentions.

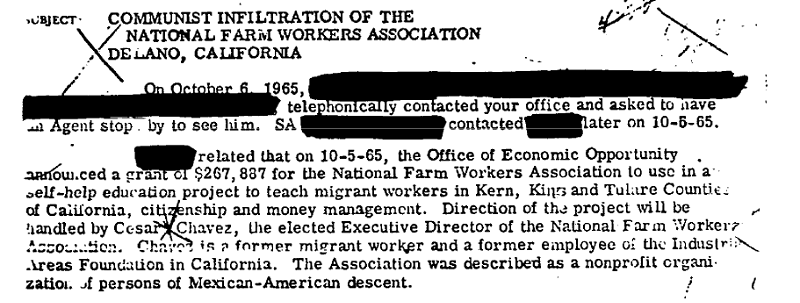

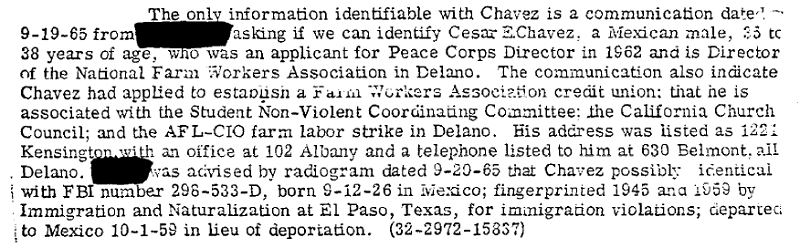

Previously processed FBI files released to Beryl Lipton begin with a memorandum (“Communist Infiltration of the National Farm Workers Association”) dated from October of 1965 identifying Chavez as a Mexican-American between 35 and 38 years old and as Director of the Delano, California-based National Farm Workers Association.

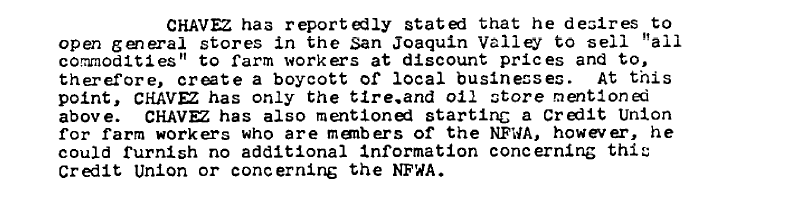

The document also made note of Chavez’s intentions to start a credit union on behalf of the financially-troubled Filipino and Mexican farm workers whom he sought to represent, as well as the fact that Dolores Clara Huerta, a woman closely associated with Chavez’s movement had secured a $267,887 grant for the NFWA from the Office of Economic Opportunity.

An FBI source, whose name has been redacted, suggested that Chavez was “not qualified to manage this large a sum” - this same source had also “heard” that Chavez had only attained “a grammar school education.”

The unnamed source told FBI agents that he had become interested in Chavez’s background and activities due to concerns that the labor leader may have been involved in “subversive activities.”

Though this same informant had not found reason to believe Chavez was in fact an agent of the anti-capitalist agenda, he did choose to challenge the popular conception of Chavez as a genuinely concerned leader of the NWFA, an organization the source felt existed only “supposedly to improve the wages and living conditions of the migrant farm workers in Kern and Tulare Counties.”

The source continues, “Chavez is not altogether sincere in his desire to assist migrant workers, but is solely interested in making a name for himself and to gain financially.”

Though one struggles to imagine the mental gymnastics necessary to construe the refusal to work as a potentially lucrative scheme, the FBI did add this testimony to a list of accusations leveled against Chavez: notably that he “associates with ‘left wing’ type individuals” and that he “has openly been called a Communist at Delano City Council meetings.”

Aside from the means by which one might profit by leading a group of people to refuse to work, basic Spanish also seems to be high on the list of things that confuse the Bureau. Several times throughout the memorandum, an FBI translator had to clarify to both sources and interviewing agents that the word “huelga” (often scrawled across picket signs) is the most direct Spanish translation of a workers’ strike.

Due to a pretty obvious misinterpretation (on the Bureau’s behalf) of Chavez’s belief that “[huelga] means much more [than strike] to the Mexican farm workers” and one individual’s claim that the word could refer to “revolt,” the reader can almost feel the palpable air of excitement that the possibility of communist subversion brought …

until a brief parenthetical from a “Bureau translator” clarifies that a Spanish speaker wouldn’t use that specific term to suggest revolution - again, “huelga” simply means “strike” or “to leave the place vacant.”

Due to increased pressure from businesses involved in the California Grape industry as a result of the boycott of California grapes initiated by Chavez in late 1965, the tides began to turn in favor of the farm workers - though the FBI would have you believe otherwise:

Nevertheless official union negotiations were underway by the beginning of 1966. In the wake of Schenley Industries - one of the two largest companies involved in the production of grapes in Delano - acknowledgement of the Union formed by Chavez, an employee of the company (whose name was redacted) mailed a letter to the “Honorable J. Edgar Hoover,” notorious head of the FBI throughout the cold war era.

The letter alludes to Chavez, as head of the NFWA, and Sidney Korshak, an attorney for Schenley (apparently “well known to the Bureau”), who had executed an agreement that effectively legitimized Chavez’ union and signified one of the first tangible examples of increased labour rights for the migrant farm workers of Southern California.

The author of the letter apologizes profusely to Hoover, claims he had no knowledge of the agreement and does not approve of it, and elects to quote Julius Caesar: “the die is cast.” Whoever wrote the letter offers that “there is no alternative to close the ranks and make the most of the situation.”

Besides further illuminating the nature of J. Edgar Hoover’s eerie and far-reaching influence on the America of the 1960s, this letter is suggestive of just how extensive FBI involvement in “subversive” activity of any kind was during the post-McCarthy era. These communications highlight the degree to which all were beholden to the agenda of a communism-panicked regime and the extent to which federal agencies interviewed and recorded the activities of those even remotely associated with left-wing activism.

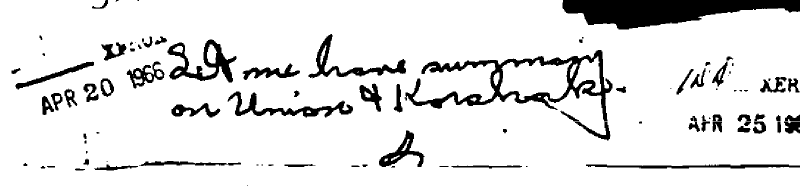

We’ll close out this chapter of Chavez’s file with Hoover’s handwritten note in response to the letter:

The first file has been embedded below, and the rest can be found on the request page.

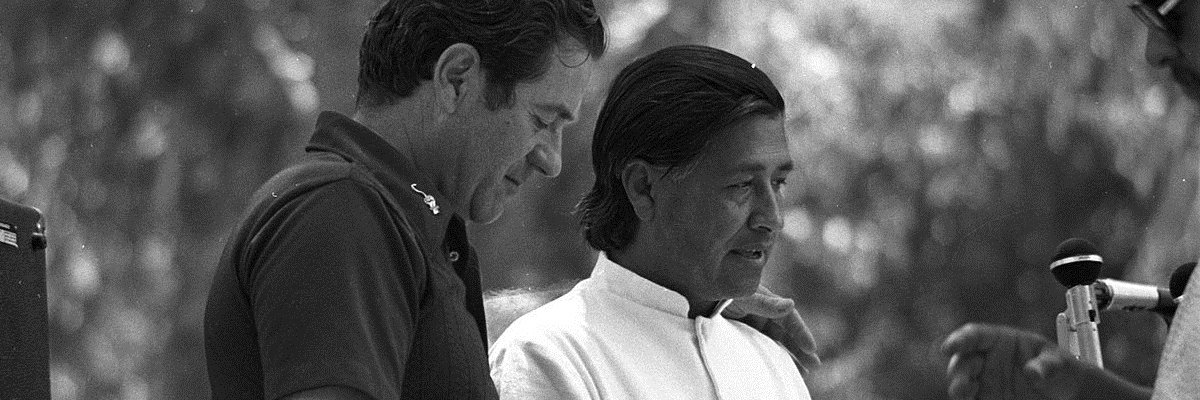

Image via Wikimedia Commons