The North Eastern Massachusetts Law Enforcement Council (NEMLEC) has released its policy on use of force. NEMLEC thus joins law enforcement agencies and criminal justice experts across the country in concluding that this basic document is fit for public consumption.

Until recently, NEMLEC resisted disclosing its use of force policy. But its rationale was notably different from the more common arguments used by police records offices attempting to reject such requests. Rather than arguing over whether this record or that was releasable, as of last month, NEMLEC’s lawyers argued that none of its documents were public in the first place.

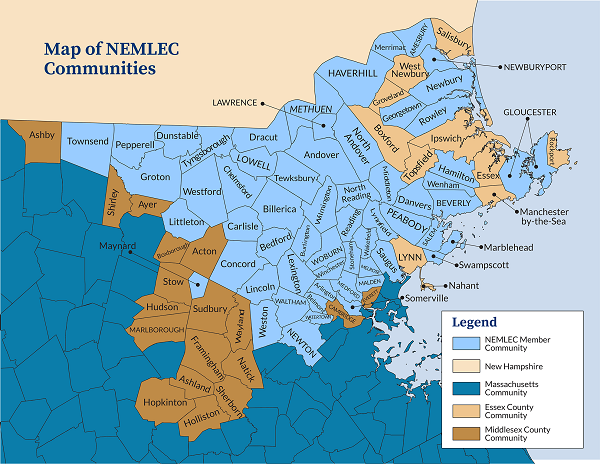

NEMLEC coordinates SWAT, K-9, and other specialized operations for more than 60 communities. Its members include the Greater Boston police departments of Newton, Watertown and Somerville, the coastal cops in Newburyport and Marblehead, and the small towns adjacent to New Hampshire.

A group of police chiefs formed NEMLEC in 1963 to share strategies, and formally incorporated as a nonprofit in 1969. By pooling monetary dues, NEMLEC members split burdens that otherwise would be prohibitively costly, like SWAT equipment and cyber crime analysis. Members also share personnel for large-scale operations such as search-and-rescue and SWAT raids.

There are a handful of similar groups across Massachusetts, including the Central Massachusetts Law Enforcement Council (CEMLEC) and the Metropolitan Law Enforcement Council (MetroLEC).

Yesterday, the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts published nearly 900 pages obtained via a lawsuit settlement agreement with NEMLEC. The release includes the policy for use of force by officers participating in NEMLEC operations, including SWAT and rapid response team operations.

“NEMLEC recognizes that the rapid response and presence of a highly trained operational unit can resolve dangerous situations with a minimal use of force,” the policy begins. “It is emphasized that the most successful operation is one that results in the resolution of a problem without injury to anyone,” it continues.

As is standard, the NEMLEC use of force policy prohibits firing warning shots, as well as shooting from a moving vehicle except under dire circumstances.

The NEMLEC policy outlines a continuum of force options and reporting requirements when officers resort to any of them. Officers must consider the amount of resistance from a suspect, as well as the “physical odds against the officer.” Relevant factors include the size, age, and physical condition of the suspect.

The policy establishes a common standard of conduct and accountability for NEMLEC operations, many of which involve tactical teams. But before last month, NEMLEC insisted that this document was not a public record.

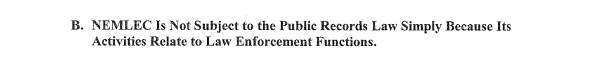

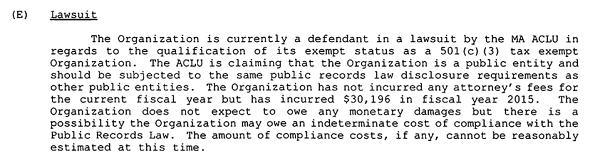

In June 2014, the ACLU of Massachusetts sued NEMLEC for records pertaining to SWAT operations. Lawyers for NEMLEC asked the court to dismiss the suit in October 2014, arguing that the Massachusetts public records law does not apply to non-profit entities, regardless of their function.

NEMLEC argument hinged on weaknesses in the Massachusetts public records statute and case law. Shoddy wording in the state’s transparency law has allowed the governor to skirt public records obligations, as well as police departments at private universities. NEMLEC cited both cases to assert similar immunity.

“Because NEMLEC is not an entity within any of the categories” of agency specified in the Massachusetts statute, their motion argued, “it is not subject to the Public Records Law.”

NEMLEC walks and talks like a law enforcement agency in some pretty clear ways - developing its own policy for use of force is one of them, as is purchasing such specialized equipment as armored vehicles and license plate readers. But the group fought ACLUM’s lawsuit for months, leaning on its nonprofit status to justify withholding documents.

In June, NEMLEC reversed its position and settled the lawsuit brought by ACLUM. Its membership voted that, “as an instrument of law enforcement and public safety, NEMLEC should be subject to public records disclosure and should comply with public records requests.”

“At its core, NEMLEC is a public safety agency, and we hold ourselves to the highest standards of law enforcement,” said executive director Laura Nichols in an accompanying statement.

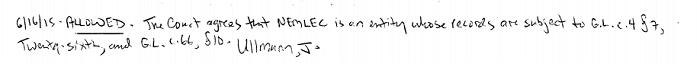

The joint filing signed by both NEMLEC and the ACLUM likewise makes clear that “NEMLEC is an entity whose records are subject to the Massachusetts Public Records Law.”

In a handwritten note, the judge overseeing the case explicitly lent his endorsement, as well. Other law enforcement councils around Massachusetts have been following the case closely, and are reportedly reviewing their own records policies in light of the NEMLEC settlement.

“It’s the right thing to do,” said Carlisle Police Chief John Fisher, the current president of NEMLEC’s executive board, to the Associated Press.

By email, Fisher told MuckRock that the vote to amend NEMLEC’s records policy was unanimous, with all 61 current members voting in favor of releasing documents and none opposed. Neither Chief Fisher nor Ms. Nichols elaborated as to what swayed NEMLEC members in favor of transparency.

The end result here is progress. But the NEMLEC case highlights dire gaps in the Massachusetts transparency law. NEMLEC spent $30,000 of taxpayer funds on the lawsuit before acknowledging its own disclosure obligations as a public safety agency. The court endorsed the settlement, but it’s not clear that NEMLEC would have been ordered to release documents if lawyers continued to press for immunity.

As MuckRock has argued before, the state’s public records law lags behind other states. When it comes to whose SWAT team records are public, the matter shouldn’t be settled by a vote of the cops themselves.

Image via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0