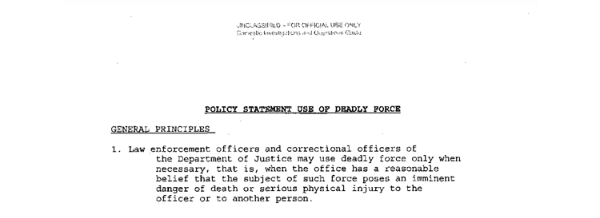

Earlier this week, a Boston Police Department officer and an FBI agent fatally shot a man. As both agencies have released their policies on use of deadly force, the public knows the standards that the officers were taught when it comes to pulling the trigger, and how both agencies will review the shooting of Usaama Rahim.

If the shooting had taken place across the Charles River in Cambridge, the public would not have the benefit of this basic information. Last month, Cambridge Police Department denied a public records request in full for its use of force policy, arguing that releasing such materials might jeopardize investigations and put officers at risk.

Use of force policies establish what level of force, if any, is appropriate in a given situation. They make clear when officers may fire at a suspect, physically restrain them, or use other non-lethal tactics. In cases in which law enforcement officials use deadly force, such as in the shooting of Rahim on Tuesday, the policy dictates the chain of reporting and post-incident review process.

In an e-mail last month, Cambridge Police Department spokesman Jeremy Warnick replied that releasing the policy would hamper investigations, and “more importantly, officers following these policies and procedures may also be placed at risk when engaging dangerous suspects.”

By contrast, the Boston Police Department posts its entire manual online, including use of force procedures. The FBI also has released its use of deadly force procedures as an appendix to its operations guide. The Somerville Police Department, another large agency in Greater Boston, provided a copy of its policy within hours of a public records request being filed and without any material being blacked out.

“As many eyes as you can have on it, the better,” said Lieutenant Mike McCarthy, a Boston police spokesman, about the Boston Police policy.

“They’re not just to outline what’s expected of officers,” McCarthy said, noting that use of force protocols are as much for the public as for cops on patrol. “It’s important to educate the public on what we’re instructed to do.”

The Boston Police policy, for instance, forbids officers from firing warning shots. Officers may pull the trigger when “there is no less drastic means available” to defend themselves or others from an attacker.

McCarthy also sees a deterrent effect in publishing detailed policies online.

“If we’re met with a level of resistance,” he elaborates, “if you know our response to that will be the use of pepper spray, then you may be less inclined to do that if you know you’ll be sprayed in the face.”

Boston’s policy for use of deadly force was last updated in 2003, and is currently being reviewed for potential revisions. BPD has a separate policy on use of non-lethal force, such as pepper spray, which was last updated in April 2013.

As does BPD’s, Somerville’s use of force policy prohibits shooting from a moving vehicle, and directs officers to issue a verbal warning before using deadly force, if circumstances allow.

Per SPD policy, which the department released in full upon request, the preferred verbal warning, is “Police Don’t Move.” Somerville updated its use of force policy in March 2015.

These policies are both a training tool and an accountability standard. Since Eric Garner’s death last July in Staten Island, the New York City Police Department’s procedure has taken center stage. The policy, which NYPD released in full before Garner’s death, explicitly bars officers from using chokeholds, defined as “any pressure to the throat or windpipe, which may prevent or hinder breathing or reduce intake of air.”

After the medical examiner determined that Garner died due to “compression of neck (choke hold), compression of chest and prone positioning during physical restraint by police” and video of Garner’s arrest was posted online, protests across the country called on NYPD to review the officer’s tactics.

Daniel Pantaleo, the NYPD officer who arrested Garner, insists that he did not use a chokehold, but used a standard takedown technique. The department is currently investigating whether Pantaleo violated policy.

Warnick, in summarizing his department’s policy, said Cambridge directs officers to use “only a reasonable and necessary amount of force” when making an arrest.

“Since our officers will encounter a wide range of behaviors,” Warnick elaborated, “they must be prepared to utilize a range of force options to maintain and/or reestablish control by overcoming resistance to the officers’ lawful authority while minimizing injuries.”

But Cambridge Police would not provide actual language from the policy, citing two exemptions to the Massachusetts public records statute. The first exemption allows agencies to withhold internal personnel rules, but only “to the extent that proper performance of necessary governmental functions requires such withholding.” The second provision permits law enforcement to withhold investigatory materials if their disclosure would hinder effective law enforcement.

Warnick said that “public disclosure of these policies and procedures would enable individuals to circumvent such procedures.”

Open government advocates said they disagreed with the Cambridge Police Department’s reading of the statute, as well as the suggestion that releasing the policy would endanger officers.

“The public needs to know how its law enforcement operates, particularly when it comes to the use of force against citizens,” said Justin Silvermancq, executive director of the New England First Amendment Coalition, which supports expanded public access to governmental agencies and documents.

“The public records law provides exemptions, but narrow ones that do not allow a police department to withhold documents based on vague concerns,” Silverman said.

“It would be in everyone’s interest for departments to explain how their officers are trained and to share these policies. That type of transparency builds trust with the public and assures communities that their police departments are operating as they should be.”

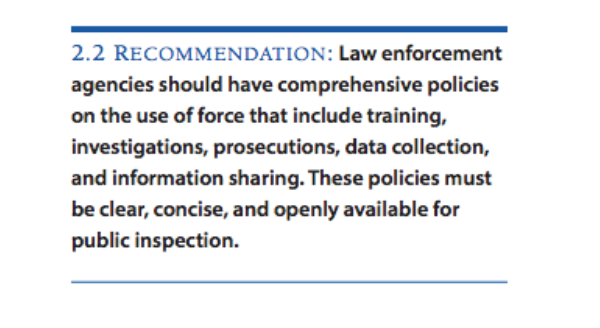

A White House task force report released last month emphasized that police departments should have comprehensive policies and training on the use of force. The task force specifically recommended that such “policies must be clear, concise, and openly available for public inspection.”

Laurie Robinson, co-chair of the White House task force and professor of criminology at George Mason University, views transparency as critical for effective law enforcement.

“Having key policies open to public inspection — whether posted online or available at the police department — is very important for the public to have confidence in policing in their community,” Robinson said.

Asked about the White House recommendations and publication of use of force policies by other departments, Cambridge police reiterated their position.

“While we certainly appreciate and support transparency, we reaffirm our original response and concern that our officers may be placed at risk when engaging dangerous suspects following the release of these requested policies and procedures,” Warnick said.

Cambridge City Hall declined to comment on the police department’s response, as did the city’s police civilian review board. The matter is currently on appeal with the Massachusetts public records supervisor.

Image by CaribDigita via Wikimedia Commons