Yesterday, the Cambridge Police Department released its use of force policy. Previously, the department had said that publicly disclosing its policy would put officers at risk.

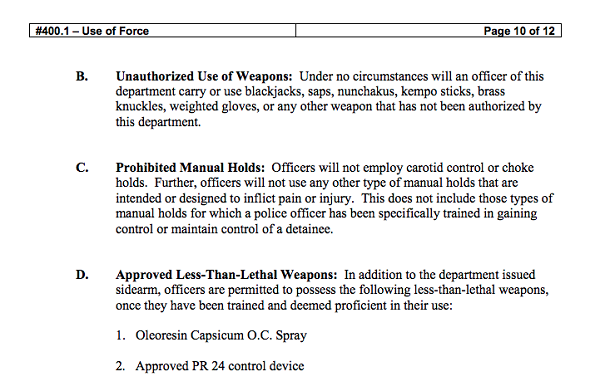

Tucked among the previously undisclosed provisions is the department’s ban on a number of weapons, including “blackjacks, saps, nunchakus, kempo sticks, brass knuckles, weighted gloves, or any other weapon that has not been authorized.”

Like the NYPD, Cambridge prohibits officers from using chokeholds to subdue a suspect. New York’s finest tried to charge a princely sum for a digital copy of its manual, but CPD initially rejected outright MuckRock’s request for its use of force policy.

As we reported last week in partnership with the Boston Globe, Cambridge police officials claimed that releasing the policy would hamper investigations, and “more importantly, officers following these policies and procedures may also be placed at risk when engaging dangerous suspects.”

Two other large police departments, Boston and Somerville, provided their use of force policies in full upon request. Boston Police Department and even the FBI post their policies in full online, as do many law enforcement agencies nationwide.

Cambridge posted the policy online on Tuesday, along with guidelines for reviewing incidents where officers fire their guns or restrain a suspect. In an accompanying statement, the department said that the shift toward disclosure followed “an ongoing, constructive dialogue within the police department, City Manager’s office, and between the police and the Cambridge community.”

“The Cambridge Police Department recognizes and respects the public’s desire for transparency within government agencies,” the statement reads. “We believe that transparency can reinforce trust between the police and the communities they serve.”

In releasing the policy, Cambridge pointed to MuckRock’s public records request as a major catalyst, as well as a White House task force report released last month that recommended that use of force policies should be open to public inspection.

Such policies establish the appropriate level of force deal with specific situations. In cases in which law enforcement officials use deadly force, such as in the shooting of Ussamah Rahim last week by a Boston Police officer and an FBI agent, the policy dictates what happens next, in terms of reporting and reviewing the incident.

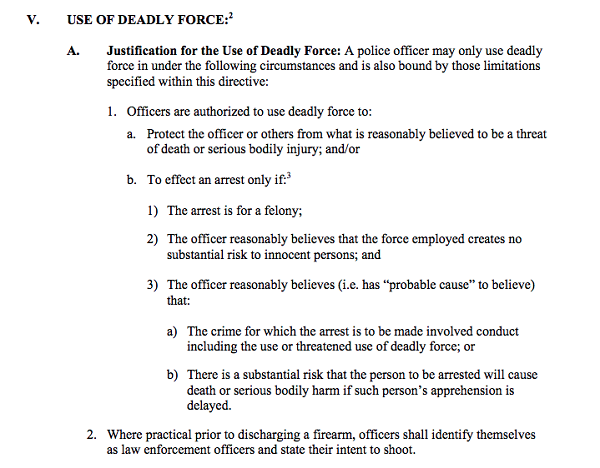

Per the nationwide standard, Cambridge directs officers to use the least amount of force necessary. The policy, which was last updated in 2011, permits officers to fire their weapons only to protect against “a threat of death or serious bodily injury,” or to make a felony arrest under narrow circumstances.

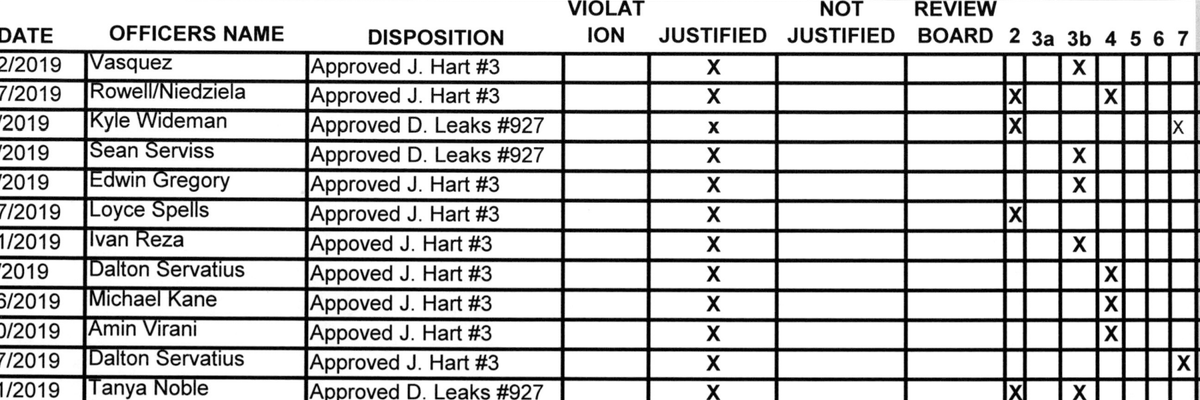

The policy requires officers to give a verbal warning before pulling the trigger, if possible. Even if they do not fire, officers must report all incidents when they point their firearm at a suspect. Cambridge also posted a blank copy of this reporting form to the department website, along with procedures that police supervisors follow when investigating use of force incidents.

After using any forceful tactic, officers must evaluate suspects to determine need for medical attention.

Prior to Tuesday, such particulars of CPD’s use of force policy and standards were not known.

Open government advocates lauded the release, but criticized Cambridge police for rejecting the original request.

“This is the right outcome, but the wrong process to get there,” said Gavi Wolfe, legislative counsel for the ACLU of Massachusetts. “Basic transparency should not depend on public and political pressure being brought to bear.”

“There was no legitimate basis for Cambridge to have withheld its use of force policy in the first place, but our weak public records law allows officials to keep information from the public without consequence,” Wolfe said.

“While it may be a little late in doing so, the Cambridge Police Department is ultimately making the right decision to release its use of force policy,” said Justin Silverman, executive director of the New England First Amendment Coalition, which supports expanded public access to governmental agencies and documents.

“The CPD now appears to be in the company of other police departments who acted in accordance with the state’s public records law,” Silverman said. “I hope the CPD will continue to provide records when requested and respect the public’s right to know.”

Cambridge police indicate that they will post other procedures online in the coming weeks.