Three months ago, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) John Sopko announced that Thomas C. Niblock would become the office’s senior representative in Kabul. The first report released post-this announcement would be in the form of an Inquiry Letter to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

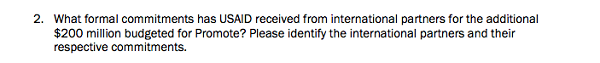

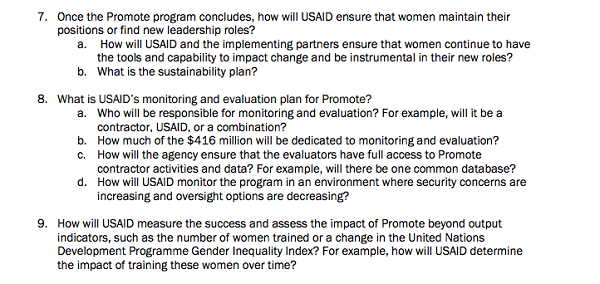

At this point SIGAR had some questions about USAID’s women’s empowerment program Promoting Gender Equity in National Priority Programs (Promote). Where was the money coming from? Where is it going? Really, what’s the plan here?

Not so many unusual questions from the agency tasked with investigating misused or misplaced funds in the struggle to rebuild Afghanistan. USAID provided its responses a day before the SIGAR-appointed deadline.

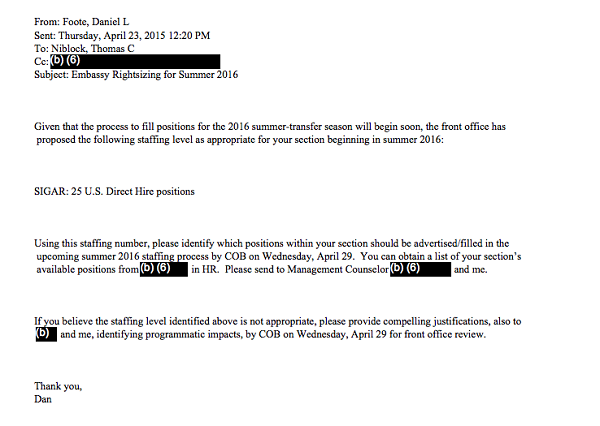

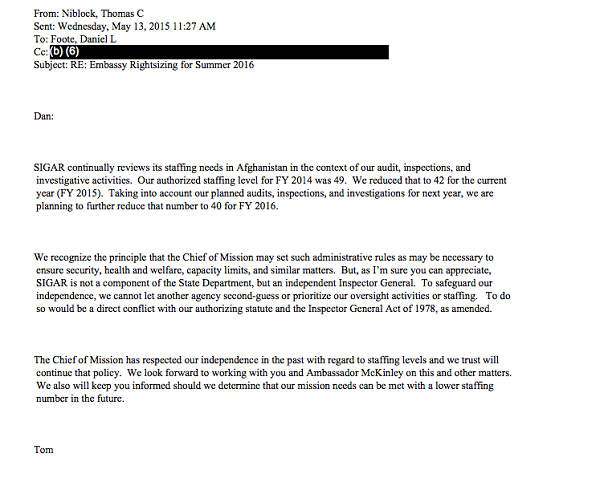

Later that week, Niblock, his seat still warm from his predecessor, received an email from his friendly very-local United States embassy, “Subject: Embassy Rightsizing for Summer 2016.”

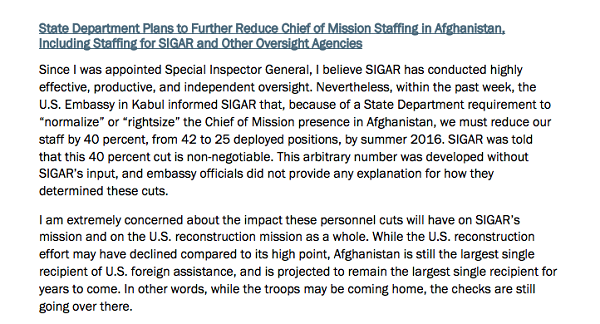

Tasked with oversight of agencies funnelling U.S. funds into the country, the State Department direction felt like a sort of shakedown. The email requested a response from SIGAR by April 29, the day Mr. Sopko was to provide testimony to the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Subcommittee on National Security to make a case for the importance of keeping clean and accurate data. He was “extremely concerned” about the proposed staffing reduction, what with the billions of dollars poured and pouring into Afghanistan and while personnel from other agencies were also leaving the region.

One official suggested that the cuts were part of a sort of unwanted roomies situation; SIGAR is located in the Embassy in Kabul. Two weeks after the State Department’s requested response date, Tom sent Dan a response. They’d be keeping their staffing levels as they like, but they’d let State know if they felt the urge to do it differently.

Would-be proponents of Promote are wary of the promises it makes. The Inspector General echoed Afghanistan First Lady Rula Ghani’s concerns that the enterprise would generate paper but not progress.

“The concept is brilliant, “ said female Afghan parliamentarian Farkhundah Naderi back in 2013, when the program was still going by the working name Women in Transition. “But I hope there is going to be very strong monitoring … At the end of the day, effectiveness is so important.”

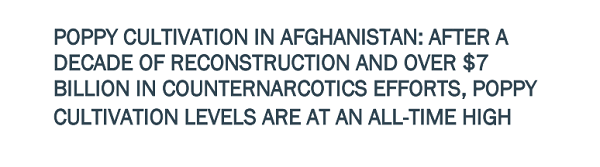

It’s a concern that plagues many reconstruction efforts, in particular the ever-present reality of opium production in the Middle Eastern country. SIGAR’s latest report on opium production bore a title that inspires little confidence.

When asked to what extent opium cultivation is the white elephant in any discussion of waste and fraud in Afghanistan, the Press Officer turned our attention to three documents: Future U.S. Counternarcotics Efforts in Afghanistan; the October 30, 2014 Quarterly Report to Congress; and the High Risks List.

SIGAR’s feelings seem pretty clear. In a country receiving billions of dollars to improvement efforts, the fact that the drug problem fuels 90% of the world’s opium, heroin’s source, and a sixth of the national GDP puts other efforts in Afghanistan at high risk of failure.

On Monday, the Taliban took credit for an attack at the Afghan Parliament on the occasion of the country’s third attempt to confirm a Minister of Defense. Two were killed and dozens more injured, as the U.S. continues to provide aid to Afghanistan, which has received more funding than post-World War II efforts in Europe with not-so-comparable results.

MuckRock will be filing requests more requests regarding the use of U.S. aid funds, but you can help tackle this knot as well. Get in touch, and we’ll help you start pulling at your own threads.

Image via SIGAR quarterly report