America has been fighting an ongoing battle against prison overcrowding for decades now, and the preferred method of treatment has been more prisons. Such a wide reaching problem has always been difficult to tackle, and the symbolic function of punishment repeatedly runs up against its practical elements.

Bernie Sanders recently made private prisons a national political issue when he introduced the Justice Is Not For Sale Act into the Senate, but for-profit incarceration, just like America’s inflated prison population, is no new beast. However, it is one with a fine public relations team and a corner of the market seemingly small enough to discount their impact. Or so you’d be led to believe.

Let’s take a look at the most common myths and misconceptions surrounding the incarceration industry.

1. They’re a reaction to, not a cause of, prison crowding.

If you go back to the eighties and nineties, one can make the argument that modern-day behemoths like Corrections Corporations of America or GEO Group Inc. (née Wackenhut Industries) saw an opportunity and stepped up to the plate, to the benefit of shareholders and government partners alike.

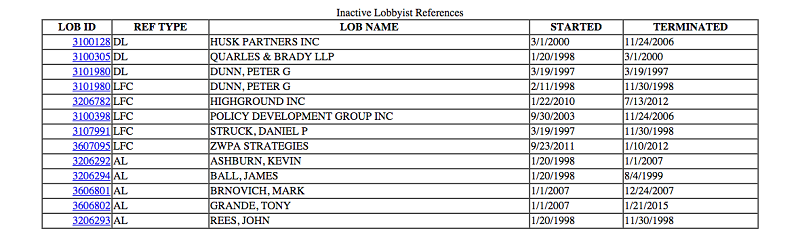

But since then, there’s been a series of crossovers between the public and private correctional worlds, and the extent of the back-and-forth is not easily quantifiable in pure dollar signs. For example, consider Arizona, where the Attorney General Mark Brnovich was once a registered lobbyist for CCA.

The attorney then brought a suit, alongside two dozen other states, against the president’s move to grant amnesty to millions of immigrants.

In California, CCA also recently noted that they were in talks with representatives in Sacramento.

The constant overlap of players and the seemingly lax conflict of interest rules for those moving between the private and public sectors makes it difficult to talk about the private prison system as a whole having no influence on how mass incarceration is actually being treated, as opposed with dealt with, by those whose jobs it is.

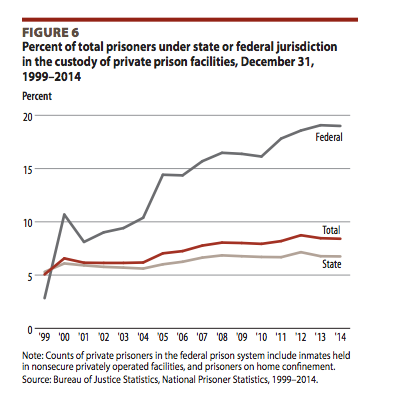

2. They’re a relatively small part of the problem without much influence on the system as a whole.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that private operators contain nearly 20% of the federal population, with bites more taken out of various state systems: 16.5% in Arizona; 18.3% in Colorado, 38.7% in Montana, 24.3% in Hawaii.

Market diversification is key. The distribution of private prisons would suggest that the south is carrying most of the weight of private operators. But private prisons hold immigrants, women, sex offenders, people from every corner of this country.

What’s more, American correctional standards have been a sort of standard for policing and punishment abroad, and GEO Group maintains global operations in New Zealand and the U.K. What hasn’t been working for America has been exported anyway.

3. They work for the government, so even though they’re not open to public inspection, the courts and the oversight committees keep them in check.

Whenever the word “inefficient” is lobbed at the government, reasonable defenses make themselves scarce. No one would argue that Uncle Sam is the most organized, most thoughtful, best man for the job — enter private business.

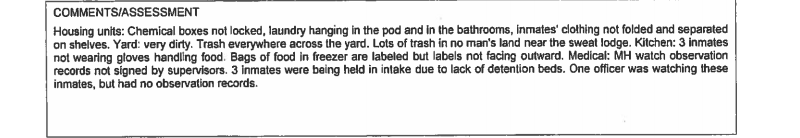

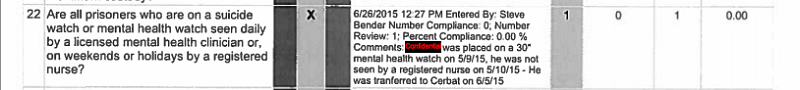

But just because the government has hired someone to watch over a prison contract doesn’t mean that so much will come of any wrongdoings they find. Consider in Kingman, where an inspection of the prison noted that the facility was deficient in multiple areas.

The following month, there was a riot, and the Governor ordered an investigation into the facility, ultimately declaring that the operator, Management and Training Corporation, would be losing its contract. But the problems that it had — staffing vacancies, improper medical treatment, shoddy record keeping — were noted even before they bubbled up to the surface.

4. They don’t profit off of the inmates themselves.

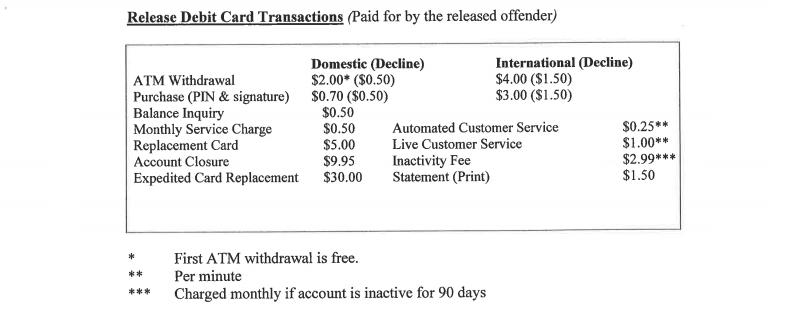

There are plenty of ways that prisons can profit off of their inmates: labor, room and board, commissary fees, telephone commissions.

Just because a company is under government contract, doesn’t mean that it isn’t entitled to some of the same cost-saving measures that have been built into the system all along. What it does mean, though, is how those numbers affect their bottom lines is their business, not ours.

5. They save money.

Does anyone actually have proof of this? Seriously, is anyone sure that this happens?

Given the incidentals — contract monitoring, utility provision, external medical bills — the argument that privately-operated prisons are a cost-saving measure with no loss in quality has been thrown about with almost no actual explanation.

The argument that operators handle low-stress offenders has been leveled and then retracted, but it’s important to consider which share of the population these operators are courting.

Which is part of why they are an important indicator of how our criminal justice system is faring. If private prisons are meant to hold overflow, then the continued existence of private prisons is in some measure a sign that we’re failed to manage our incarceration on our own.

“If you build it in the right place,” a CCA executive told The Wall Street Journal, “the prisoners will come.”

In America, that belief still holds true.

Image via Pixabay.com