On March 5, 2012, Tom Weil, City Manager of California City, California, signed a letter to a lawyer from Fort Lauderdale. “Speaking from over 12 years of experience,” he wrote, “you will not find a better partner in the business world.”

The partner was Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the most successful for-profit prison company in the United States. Well-established in dozens of jurisdictions but perpetually battling public distaste, CCA, like any dynamic business, is ever-exploring new opportunities, and there seemed one to be had in rural Southwest Ranches, Florida. The letter was among a collection of documents recently released by the City of California City.

Mr. Weil hit all of the CCA selling points. The opening of CCA’s California City Correctional Facility “truly created a win - win scenario for the City; Jobs for the citizens, a robust housing and rental market, and economic activity for our local businesses.” After a decade of working with CCA, they had “added over a million dollars to the Kern County tax rolls” and hundreds of new community members without fear of imported crime; they could rest assured that detainee families would be too wary of federal detection to settle nearby and immigrant inmates would be shipped away at the end of their detention.

“I do hope you have the opportunity to develop the relationship with CCA that we have with them in California City,” he wrote.

The next year, Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced the end of its relationship with California City.

In contrast, Southwest Ranches, Florida, didn’t even get a prison. In fact, by the time Tom Weil’s letter would have made it to the East Coast by standard mail, CCA had already filed a complaint in court against nearby Pembroke Pines for allegedly reneging on an agreement to provide water and sewage services.

CCA had been in talks with the town for years - they got infrastructure on the town docket as early as 2005. Their agreement indicated that the town would enter into intergovernmental service agreements in partnership with CCA. The town would get a cut of the per diem rate and together they’d work to “assertively contact and identify.”

CCA would provide the necessary information and, when able, the inmates.

But a dedicated contingent of local Floridians challenged the new prison, and the Council began to stall, CCA claimed in the lawsuit, Corrections Corporation of America et al v. City of Pembroke Pines, which they lost in 2014.

One can see CCA’s frustration. From a business standpoint, sudden opposition is disruptive.

The collection of materials from California City is a guide to a different sort of relationship than what the City Manager’s letter would have had you believe. They can’t help but suggest a puppeteering of the community, a sort of monkey-in-the-middle between federal government contractors and prison companies and the towns where the other two want to operate.

In the last two years, CCCF has been transferred back into the management of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) under a lease of the building and land from CCA. The company itself, for all intents and tax purposes, has converted into a Real Estate Investment Trust, which has seemed to indicate a repositioning of interests; property is a more useful business model than the admistration of corrections, which repeatedly takes a lashing.

CCA’s lawyer in Florida had bemoaned the political nature of the opposition, and it’s a lament that won’t get old soon. Bernie Sanders and Hilary Clinton have introduced the abolishment of the private prison to the modern Democratic agenda, while the federal government itself is the top customer.

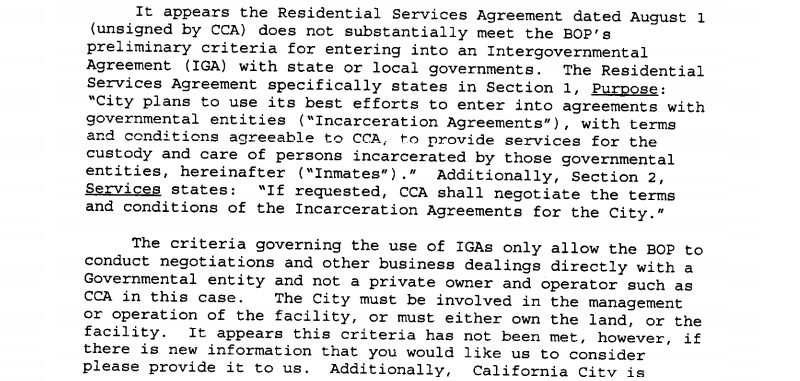

CCCC’s introduction to federal prison opportunities presented itself in 1999. A letter from then City Manager Jack Stewart to Bob Newport, Senior Deputy Assistant Director at the Bureau of Prisons, indicated that they’d discussed the City’s opportunities holding federal inmates.

The correspondence shows that the City had submitted an initial Residential Services Agreement to the BOP which was insufficient. “City plans to use its best efforts to enter into agreements with governmental entities (“Incarceration Agreements”), with terms and conditions agreeable to CCA…”

In response, Mr. Stewart indicated that he believed BOP “would like the option to deal directly with any manager,” but, understanding the desire to not be connected to CCA, he had removed those portions of the proposal. The Town itself had signed the version with the generous language.

Since then, the CCCC contract has passed from the BOP to ICE and USMS and back to the State of California. In a lot of ways, it may be inconsequential which entity is responsible on paper when it’s understood that the Contractor is in control. But alongside the contracts and niceties in these materials are quality assurance reports outlining numerous deficiencies. When dishonest recordkeeping, understaffing, and violence begin to sound like a private contractor’s par for the course occurrences, it’s curious that they should continue to do business.

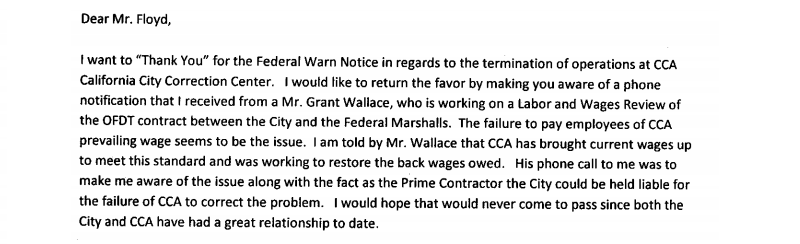

That’s what happened, though, in California City. Two years ago, CCA was found to have underpaid hundreds of workers. According to a letter from Tom Weil to the company, he’d been informed that the City itself would be held liable. It was a moment when the city could have been slapped with the weight of a dubious friendship.

In response, Mark Floyd, Managing Director of Employee Relations, informed him that the plan of action would involve re-establishing a new contract with the State. They would fire all of the employees and prohibit them from working at CCA again. They would lease the building to the State, and serve, essentially, a real estate operational role. The facility would play a new part in California’s expansive prison system.

Read part two here.

Image via The Center For Land Use Interpretation and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0