Read the first part here.

The official letter announcing the arrival of California inmates at CCA’s California City Correctional Center came a decade after it was intended.

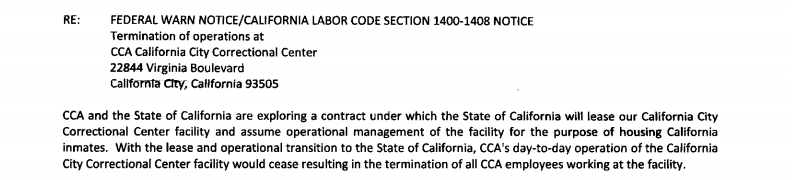

The communication, which was recently released through a public records request, was undated. It came from Mark Lloyd, Managing Director of Employee Relations, bearing the CCA logo; it related that, in preparation for the arrival of prisoners from California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, all of CCA’s employees would be fired.

When CCA initially built the facility, deep in the Mojave Desert at the tail end of the nineties, it hadn’t yet been promised to anyone. But the company always had California in mind. CCA president David Myers was confident:

California’s prisons were swiftly approaching full-tilt capacity. With the soon-to-be-unconstitutional levels of overcrowding would come the need for the CA City prison. With that would come jobs and tax revenue, a continued commitment from a corporate partner to keep a base in the City for the foreseeable future.

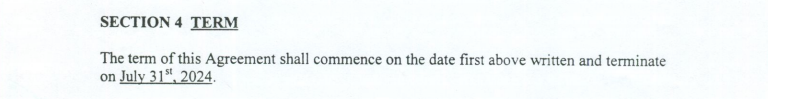

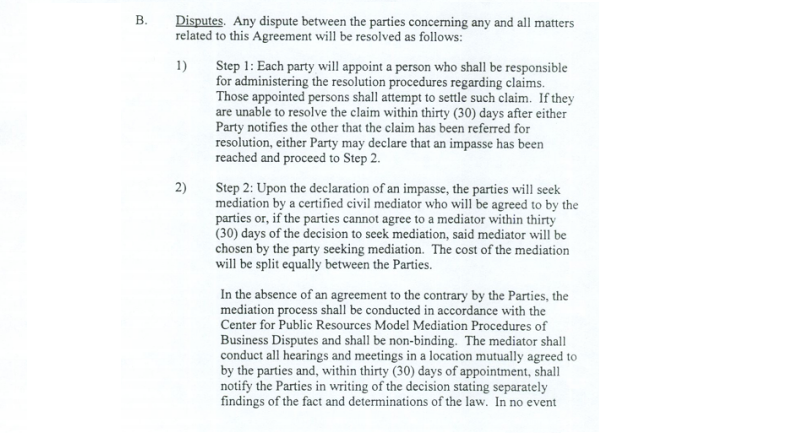

The 1999 Residential Services Agreement is no longer valid, but it exemplifies some of the more noxious elements of the company’s relationship with the City. It held California City to a partnership in which it would use its resources and intentions to aid in the hocking of CCA’s services. And then it limited its options to complain.

California City, like the prison to match, was a town built on speculation. It was the sixties, and the blanket of aspirationally-named streets still remains largely available. Current projections suggest that California City will never be a metropolis to rival Los Angeles, but CCA, after over a decade, does finally have its contract with the State of California. In the current arrangement, CCA leases the facility to CDCR, while the Department handles the administration and correctional operations.

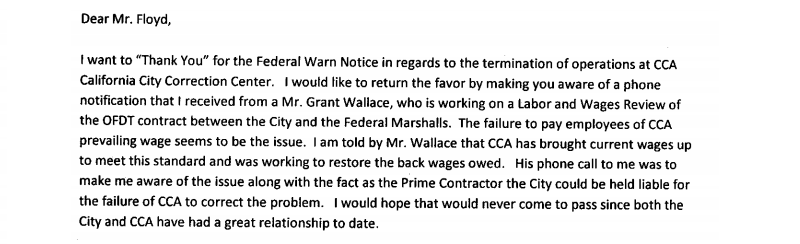

When Mr. Lloyd’s letter did arrive carrying the news, it was in response to an inquiry from City Manager Tom Weil, dated September 25, 2013. “I would like to know where you stand with correcting this problem especially with CCA moving into this new contract arrangement with the State,” he wrote.

The problem: “failure to pay employees of CCA prevailing wage.”

After a decade of working with the federal government in California City, the Department of Justice began to conduct a Labor and Wages Review of CCA’s payments to its employees. Mr. Lloyd’s letter makes no reference to it. Instead, he informs Mr. Weil that the State of California was “exploring a contract,” the terms of which would result in the termination of all of CCA’s operational management, and thus, all of CCA’s employees, who would not be entitled to get a job at any of the other locations. It would seemingly not affect the City in particular at all. A year later, the Department of Labor announced that a settlement had been reached.

The story in California City is not so unusual: a small town, in a bid for any business, plays partner, for better or worse, to a private corporation and then finds itself on the hook for loose ends. The City is potentially held liable, but the company settles and moves on.

The California Peace Officers Association put up early opposition to the prison, but through a favorable attorney general ruling and years of federal contracts CCA was able to fill the space. Since these were all managed through the City of California City, they were technically liable for violations, but they were never really in control of the prison; they were just passing along the government’s checks. In California, where the goal has been to reduce individual facility, rather than overall, population, private prisons still remain a space to put people.

An intergovernmental services agreement mutes a lot of the noise involved with the federal procurement process, and in recent years, CCA has taken to offering towns a few extra dollars for the trouble of dealing with administration of the federal agreement. For the federal government, it’s in part a straightforward way of circumventing untimely bureaucracy for the sake of “necessity.” For CCA, it’s an extra layer of protection.

The stories about private prisons in America over the last three decades have carried many of the same threads: severe understaffing, unreported abuses, dubious moral legitimacy. When CCA first constructed the facility, the reaction was disappointing. Then-warden of the then-vacant prison, Daniel Vasquez, told the L.A. Times in 1999, “Here we are with this alternative, and the state doesn’t even want to look at it.”

Even included with California City’s materials was a 1997 article from Privatization Watch reporting the abuse and swift state removal of Missouri inmates at a private Texas facility. The concept of the private prisons has always struck a discordant note. Their seeming necessity continues to sustain it.

In his letter to the Florida lawyer, Mr. Weil offers the benefits of being involved with the federal government. It can offer legitimacy to a company and a sense of security to a town. So while a settlement was reached, it dissolved the responsibility to investigate further; CCA owns operations all over the country, in towns where they’re expected to maintain the status quo but do it cheaper.

It highlights a depressing element of the way our governments negotiate on our behalf. The federal government simply asked not to know and tallied another violation when the time came. California City, in promising to work in a corporation’s best interests, also agreed to mediation terms, the likes of which are comparable to the extended administrative grievance processes found in prisons themselves.

It’s a system that continues to flourish, although the company itself has weathered numerous violations, court cases, and negative publicity nationwide. One has to wonder how that is.

California City released their materials to us without a fee, but unfortunately not all agencies are able to do so. Often, in fact, public records requests come with a noticeable charge. Consider that access to the current lease between CDCR and CCA comes with a price tag of $58.44. Curiosity comes with a price.

Beyond that, private prisons aren’t subject to the same records disclosure laws as other prison facilities, and companies like CCA and Geo Group have worked to keep it that way. Past versions of the Private Prison Information Act have had a steep climb against companies being paid to maintain the status quo, but Representative Sheila Jackson Lee has reintroduced it, H.R. 2470 this session.

Its passage would grant access to a plethora of information previously inaccessible to the public. People could better evaluate the efficiency of the deals they sign onto.

Image via California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation