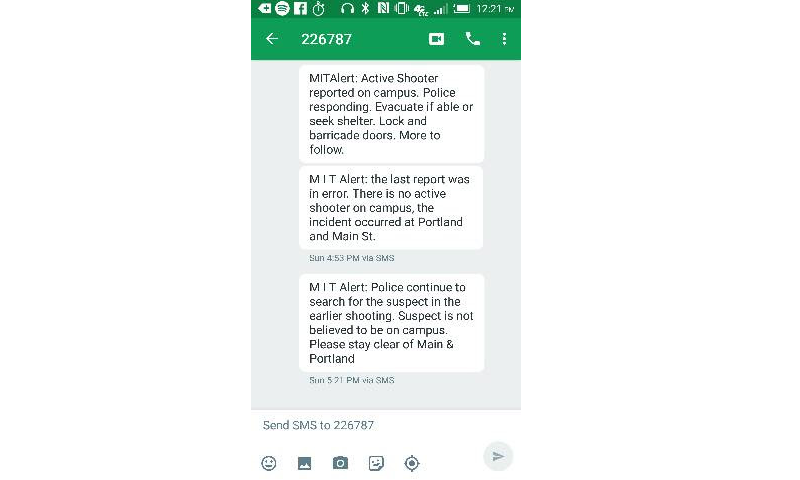

On Sunday afternoon, students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology began receiving text alerts about an “active shooter.” Subsequent updates from MIT police and municipal law enforcement in Cambridge quickly corrected that a young woman was shot a couple blocks away from campus, that her injuries were not life-threatening, and that the suspect remained at-large.

As with a fatal shooting last month in the same neighborhood, both the MIT and Cambridge police are investigating. But only one department’s paper trail is a matter of public record. Private university police have the same powers as sworn officers at public departments, but carry fewer transparency obligations under Massachusetts law.

Campus cops are empowered as “special state police officers,” a category which also includes police employed by hospitals and railroads. As of June 2015, there were 1,500 special state police officers across Massachusetts, the vast majority of whom work at colleges and universities.

Twenty-one private colleges in Greater Boston employ special state police officers. Harvard has 77 sworn officers on its roster, followed by Boston University with 67 (plus an additional 29 officers for its medical campus), and MIT with 59 officers. Wheelock College, meanwhile, which hosts fewer than 1,000 enrolled undergraduates, employs a single sworn officer.

Sworn campus police may carry weapons, make arrests and use force, just like any other officer. Statute grants special state police “the same power to make arrests as regular police officers” for crimes committed on property owned or used by their institutions. Particularly in Boston, campus borders are difficult to trace, and some of the most populous areas lie within university police jurisdiction.

Harvard’s campus spans both sides of the Charles River. Its officers, in kind, patrol not only the Yard, but also the business school in Allston and the medical school in Longwood. Twenty sworn officers have jurisdiction over Emerson College’s cluster of buildings near the Boston Common and the Financial District, while Berklee College of Music’s seven officers can make stops and arrest suspects along the heavily trafficked Massachusetts Avenue.

In July 2013, the top court in Massachusetts ruled that campus police jurisdiction also encompasses areas where students, faculty, and campus visitors “might be exposed to danger.” Many institutions also deputize officers through their respective county sheriff’s office to further extend off-campus authority.

No event illustrated the extent of campus law enforcement responsibility better, or more grimly, than the marathon bombing and ensuing manhunt in 2013. After the slaying of MIT officer Sean Collier, police from MIT, Harvard and BU were among hundreds of law enforcement that “self-deployed” to search for the Tsarnaev brothers.

Image by A Name Like Shields Can Make You Defensive via Flickr and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Hundreds of campus police are thus full officers of the law. Yet special state police are exempt from the Massachusetts public records law, which requires government agencies to release most documents upon request, including police reports.

In June, after the shooting of a knife-wielding suspect by Massachusetts state police near its campus, Boston University police rejected a request for reports filed by its own responding officers. Incident reports are typically public records when completed by municipal or state police. A BUPD lieutenant responded that his department would release the report only under subpoena.

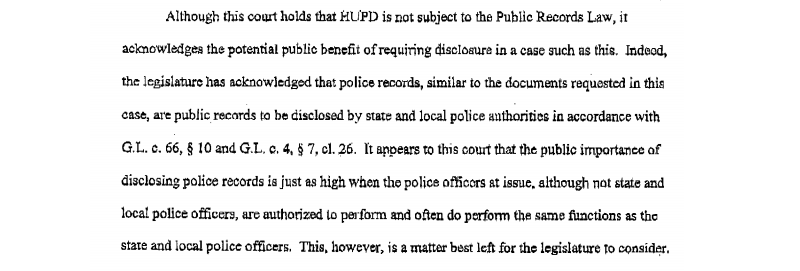

Massachusetts case law supports this interpretation. In a suit brought by Harvard’s student newspaper, the state’s Supreme Judicial Court ruled in January 2006 that the public records statute does not cover private university police.

“Simply put, Harvard University is a private institution,” the court summarized. “It follows, therefore, that records in the custody of the HUPD, a department within Harvard University, are not ‘public records’ that fall within the ambit of [the public records law].”

Massachusetts defines a public record as any document produced by a state or local government employee. A plain reading of the statute, the court reasoned, excludes police employed by non-governmental bodies.

A lower court acknowledged “the potential public benefit” of requiring disclosure by police regardless of their funding source.

“It appears to this court that the public importance of disclosing police records is just as high when the police officers at issue, although not state and local police officers, are authorized to perform and often do perform the same functions as the state and local police officers,” wrote Justice Nancy Staffier in 2004.

“This, however, is a matter best left for the legislature to consider,” Staffier concluded.

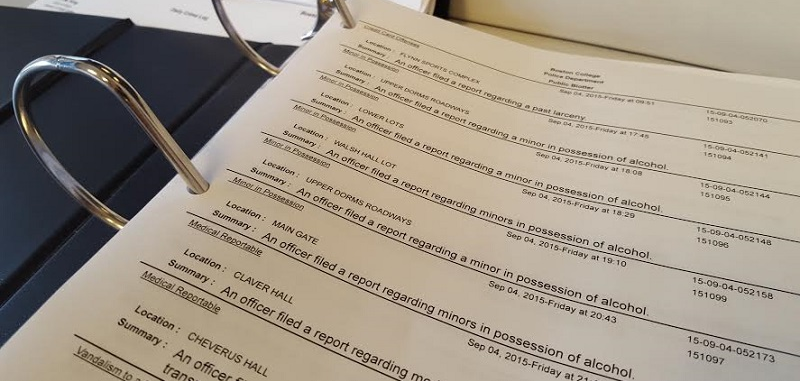

Federal and state law do mandate certain disclosures by campus police, even at private universities. Under the federal Clery Act, all educational institutions that receive federal financial assistance must publish an annual statistical report on campus crime, as well as a daily crime log that is open to the public. Massachusetts law likewise requires all police departments to maintain a public log.

College police take divergent approaches to these two requirements.

All twenty-one Greater Boston colleges with sworn police publish their annual Clery reports online. But only Harvard and MIT post crime logs to their public safety websites. Ten institutions refused to send copies of their daily logs by email, and a handful more did so only after numerous inquiries.

Neither federal nor state law requires colleges to distribute crime logs, but only to make them accessible for the public. A number of colleges solely allow people to view blotters in person.

“The Institute does not send out — electronically or otherwise — copies of its log sheets,” replied Wentworth Institute of Technology spokesperson Dennis Nealon, adding that “the log sheets here are freely available for your perusal.”

Colleges and universities in Greater Boston that employ sworn police officers.

Blue denotes an institution that sent its daily crime log upon request by email.

Orange denotes a school that refused to send its log and required on-site review.

So we took a college tour. In addition to WIT, the following college police departments refused to send copies of daily crime logs: Berklee College of Music, Boston College, Boston University, Curry College, Emmanuel College, Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Simmons College, Tufts University, and Wheelock College.

Tufts provided photocopies during an onsite review at its Medford campus. All other colleges allowed photographs to be taken of their logs, but refused to provide printouts or other copies. This included BU police, which allows the public to access its electronic crime database via a computer kiosk in the lobby.

The current BUPD chief, Thomas Robbins, was Colonel of the Massachusetts State Police until 2006. During his two years at the helm of the MSP, Robbins oversaw standards for special state police officers, including disclosure requirements. BU police did not respond to inquiries as to why its crime logs may be viewed in digital format on-site but not provided by email.

All campus police departments said that transparency is a core goal.

“We in campus policing strive to be transparent in our dealings with our campus communities not only because of the obligations imposed under Title IX and the Clery Act, but also because this is the most effective way to accomplish our campus public safety mission,” said Suffolk University police chief Chip Coletta, whose department provided its logs upon request by email.

But many argue that university police should release more than annual reports and basic logs.

“The question shouldn’t be why the public is entitled to information about how college police do their business. It should be why the public is not entitled to that information,” says Frank LoMonte, executive director of the Student Press Law Center in Washington, DC. SPLC provides legal advice to high school and college reporters.

LoMonte concedes that there is a distinction between private universities and public police on fiscal matters such as salary and travel expenditures.

“But anything that bears on how officers carry out their policing function, including their qualifications and how their conduct is regulated, is arguably already a public record under many states’ laws, and where it’s not already covered, it ought to be,” summarizes LoMonte.

“When campus police are designated as special state police, they are working on behalf of the public. For that reason, their reports should be public just as reports are of any other law enforcement officer,” echoes Robert Ambrogi, executive director of the Massachusetts Newspaper Publishers Association.

A bill currently pending before the Massachusetts legislature would do just that. Filed by Representative Kevin Honan (D - Brighton), it would revise the state public records statute to expressly cover law enforcement records of special state police officers. Rep. Honan sees the measure as a matter of consumer choice as much as public interest.

“It’s important for parents and students, when choosing a college, to have accurate crime statistics at their disposal,” Honan says.

The bill, which has been submitted several times in previous legislative sessions, is currently before a joint committee. It is unclear whether it will be taken up this session.

Six states — Georgia, Connecticut, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas and Virginia — have opened all campus police reports to the public, either by court order or by legislation. The attorney general for Indiana recently filed a brief arguing that the University of Notre Dame must release arrest reports.

Stay tuned as MuckRock will be following up on this issue in the coming weeks.

Images via the author