A version of this article appears on Motherboard

Video phone kiosks have been replacing real-life visitation in American jails and prisons — sometimes altogether — and the move is a welcome development for inmate calling services and prison wardens alike. For those on either end of the calls, though, it’s a direct line from their wallets to their captors’ bank accounts, and the government is having a hard time putting a stop to it.

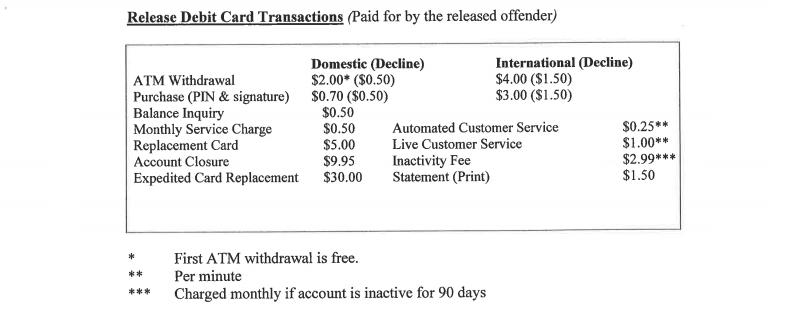

JPay, which was recently acquired by correctional technology supergiant Securus, is the most widely-used company for matters of inmate communication. In addition to the video call kiosks, they provide monitored phone services, inmate email, mp3 players, and release cards. Securus is closing in on operation in half of the nation’s jails, prisons, and federal penitentiaries; though there may be other options, Securus has been leveraging its resources to corner the market, repeatedly scoring as the top choice by Departments of Corrections looking for operators with money upfront to cover equipment, installation, and operation.

Depending on where they are, prisons don’t technically have to provide a phone service, nor do they technically have to allow prisoners visitation rights. The lack of such seemingly basic allowances was recently rectified in Texas, where a recent bill necessitated in-person visitation time for inmates. As a result, the facilities that had already moved to a video-only model applied for exemptions. Most — citing sunk costs — received them.

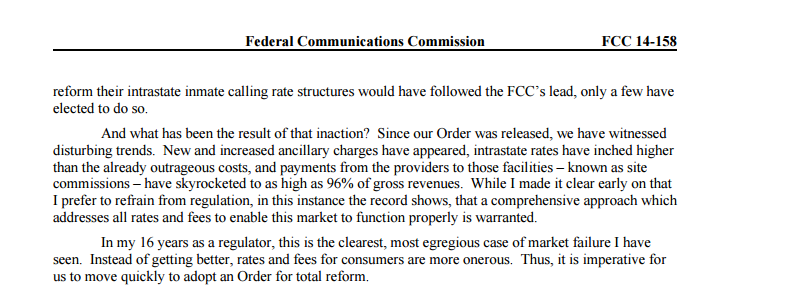

FCC Commissioner Mignon Clyburn has called the prison phone market “the clearest, most egregious case of market failure” she has seen.

It’s no secret that prison phone providers have been gouging their consumers. Last year the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) stepped in to put a cap on interstate prison calls, but, as they admitted themselves, grand reform is stymied by the possibility that intrastate rates may fluctuate and make any restrictions placed by the FCC ineffective.

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler pointed to the ICS providers behind setting rates: “There are some positive signs that reform of interstate rates has resulted in reduced rates and increased calling, but absent a comprehensive solution to the problem we will continue to find ourselves in a never ending game of ICS rate whack-a-mole.”

The problems were echoed by comments President Obama made last week, in which he highlighted the importance of a holistic government approach to reform efforts. “[W]e need state’s attorneys and local prosecutors and sheriffs and [police] departments all across this country to internalize these issues as well, because the federal system is a small portion of our overall criminal justice system, and it’s not something that I can direct by fiat to change.”

The move to video is just one example of the corporate ability to move faster than the government. Local governments specifically request that there be a revenue generating mechanism included in their communication plans. For a corporation like Securus, which has infrastructure and the funds up front to provide base costs, the lack of market competition and market regulation has been a boon, and they’ve been able to tack fees onto each step of the process.

For years, jails and prisons have needed to find their own ways to finance portions of their operations. The profit motive is built right into the contracts from the beginning; bidders must include in their responses the mechanism by which the agreement will generate revenue. By skimming off services that inmates need—visitation, phone, commissary—they’ve been able to do so.

Companies have now found that the technology they can introduce is not so much dictated by the bounds of institutional discipline or correctional best practices but by the technological advances themselves. As long as tech companies can provide local operators with the right sales pitch, they’ll be able to implement policies — like video-only visitation in Texas — and wait for the laws to catch up.

Image via Alberta Public Security