While our world-champion incarceration state racks up an annual United States taxpayer tab over $80 billion, one might assume that such dues are at least covering the costs of confinement. That one would be a victim of the transformative effects the word “assume” can have on you and me.

Over generations of American prison policy, counties and states - just like police departments - have looked for ways to recoup the expenses that accrue when society’s definition of criminality captures more people than it can accommodate. Outstanding inmate debt is now estimated at another $50 billion.

In a swath of jurisdictions, large and small, charges against inmates are extended to include those bills associated with their confinement, with wages garnished to cover fines or bills provided after the fact. It’s a debt that follows people back into the world and reappears when they return to prison.

Here are five corners where correctional institutions can cutback on their expenses by passing the bill onto “consumers.”

1. Room …

The idea of having inmates pay their own way is one of the most common in the catalog of recoup tactics, though the parameters vary. In North Carolina, counties are authorized to determine the appropriate amount to be withheld per inmate.

In Kansas, for working inmates, that amount is 25 percent of their earnings.

As debilitating as debt can be, some states have gone even further in weaponizing it - Florida, for one, has implemented a system in which prisoners looking to sue may be confronted in return with the imagined bill for their prison stay, billed at a rate of $50 per day.

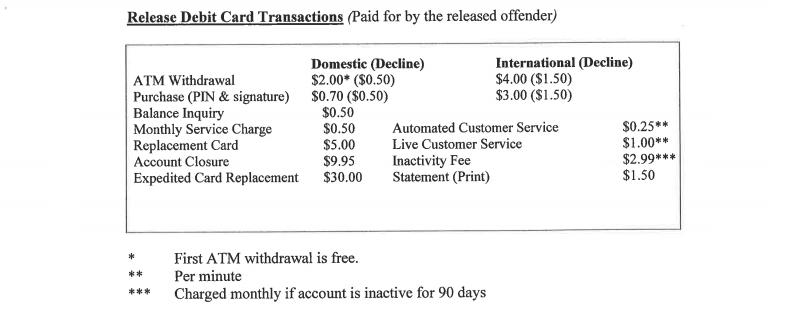

Other extras may be tacked on. In addition to the kickback commissions that facilities can get for telephone usage and commissary deposits, prisoners may also be charged for individual luxuries like the use of electrical appliances or simply charged luxury-like prices. In Riverside County, California, inmates that are deemed able can be charged over $140 a day.

2. and board

Some states have taken to authorizing a per diem rate that encompass costs a day’s worth of lodging.

Other places, like the infamous Sheriff Joe’s Maricopa County, keep a tab on a per meal basis. The sheriff implemented a rate of $1.25 per meal - he later boasted that the average meal costs only $0.56 to create.

3. Paper and postage

Though access to law materials are a typical requirement for prison facilities, this doesn’t include associated materials, like stamps and copies. It may seem like some small thing, but that cost can be another way of stymieing someone on the inside.

4. Medical care

Getting health care in prison can be difficult enough as it is. On the federal level, the Department of Justice’s Inspector General recently put out a scathing report on how personnel turnover and other issues put the BOP’s healthcare in a crisis.

While debates over access to hepatitis C treatments and sex change operations question the fairness of prisoner health care, there are plenty of counties where basic medical care continues to come with a hefty cost. Co-payments are standard in lots of states.

And what if you can’t pay? Well, many states may make exceptions for impoverished inmates. In Arizona, if one has less than $12.00, that inmate can apply for “indigent status,” but a new application needs to be submitted every 30 days.

5. Hygienic materials/clothes

Clothes, tampons, soap, and toothpaste - daily necessities can become another burden to bear, alongside the negative implications of lacking them, if you’re in a prison that charges you for them. In Connecticut, a box of maxi pads can cost $2.50. In Tennessee, a pair of pants might set you back nearly $10 dollars.

In a prison environment, where even if one works, the returns are usually just cents per day, the line between a bad day and a really bad day can be obvious and easily crossed.

As MuckRock continues to explore the criminal justice system’s nooks and crannies, follow one of our state-level requests for inmate debt data or reach out with your own stories and concerns about how the crush of cash weighs down the scales of justice.

Image via BOP.gov