In the private prison word cloud you’ll find two standouts: Corrections Corporation of America and GEO Group. The largest correctional privatization in the country and in the world, respectively, they dominate the for-profit correctional landscape.

On the New York Stock Exchange you’ll find them playing as as CXW and GEO. From the dollars-and-cents high stakes on Wall Street and the dollars-and-cents high stakes of the “Main Street” classes, the publicly-traded private prison industry provides one of the clearest direct supply chains between competing interests.

The landscape of privatized correctional services hasn’t always seemed so monolithic. In the first decade of their existence, now in its third, there were smaller outfits vying for geographic control of this new industry. Earlier forays by groups like Associated Marine Institutes and Behavioral Systems Southwest have been given up or overshadowed.

CCA and GEO Group are now the forerunners - Management and Training Corporation, the third largest and a privately-owned company, has suffered prison closings and relatively limited growth. CCA and GEO have grown through construction and acquisition of smaller companies and have thrived, part aided by and in part evidenced in their statuses as public-traded companies.

For one, it makes it easier to get insurance coverage. They’ve also absorbed more one-time government employees than other companies, with the financial advantages of being a high-level private prison executive compared with an equivalent Bureau of Prisons official are obvious.

For all the presidential year talk of private prison abolition, prison companies are banking on a stable future as far as their bottom lines are concerned. In part, this stability directly relies on government’s failure to provide for a growing incarceration population. Speaking during a recent earnings call with shareholders, CCA CEO Damon Hininger looked to the worn facilities in California as a potential impetus for growth.

“[Y]ou got a state that has got over half of their systems that are operating facilities that are 30-years-old or older, and so the opportunity is that they think about how they deal with that aging infrastructure - probably inefficiency from a staffing and operations perspective - and a lot of dollars being appropriated for [Capital Expenditures], is it an opportunity to work with the private sector to be a real solution. As I mentioned earlier, we have a lot of interest on the local level, so as I think about kind of the total opportunity providing real estate solution, I would say it is probably more predominant in local level than it is at the state level over next couple of years.”

While not as candid as shareholder calls, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings are a generally useful introduction to a company’s operations, and they’re publicly available online or via request; for example, until recently, Notes to the Unaudited Statements and tangential filings were not easily accessed on the SEC’s website but were included after a FOIA request.

CCA owns 65 total facilities. GEO Group operate or own 104 worldwide. The numbers companies provide in SEC filings provide a lot of direction but very few direct answers.

How one defines the space of prison in a tax filing is a far cry from how that same space is experienced by the people who occupy them and the towns in which they live.

These days, GEO and CCA are in the business of property. In the last three years, they’ve both made transitions to Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), categorizing them as primarily property managers, like warehouses or shopping centers or hotels; other subsidiaries are taxed according to their management and other operations - of which there is a growing array. The difference is a benefit to their taxes and a boon to their shareholders, who are paid dividends each quarter based on the company’s profits.

These dividends and other general financial information can be found in their SEC filings, where companies need to provide a basic breakdown of their earnings and expenses for the shareholders.

Companies are careful in how they present their prospects. As they say, their “forward-looking statements are subject to risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially from the statements made.”

Being in the business of buildings, CCA and GEO Group are interested in acquiring and trading properties and keeping these numbers even or growing. For them, as in any business, timing is important, and they need to keep abreast of a variety of factors - public attitude, government need, their ability to borrow and spend money for construction and operations - which can all impact their future success.

For example, CCA is optimistic in their assessment that their idled facilities “have recoverable values in excess of the corresponding carrying values” - that is, they can make up for what they’re taking as a loss - but the filings don’t necessarily have to make clear why. They do, however, have to say where those facilities are and show how much they cost to simply be held idly, which gives shareholders and the public a sense of how invested they are in getting it operational again.

Also found in the filings are other important acquisitions that have helped seal CCA and GEO’s Pac-man-like effects on privatized corrections.

CCA added Avalon Correctional Services, Inc., which operated 11 community corrections facilities in Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming as part of ongoing moves into the re-entry correctional field.

GEO also made a couple of major purchases. Soberlink, a company that makes breathalyzers, was acquired by their electronic monitoring division, B.I. Incorporated, in May 2015 for $24.4 million.

They also add eight prisons in Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas by purchasing a regional chain, LCS Facilities. The SEC filings contain a breakdown of the purchase.

Actual correctional operations are listed under “intangible assets,” as they describe. These include the worth of the contracts that dictate those operations, but the operations themselves exist far away from the SEC’s oversight.

In the acquisition of LCS, GEO gained two useful things, in addition to the buildings and the contracts, which are promising for the next two decades.

They also purchased $107.4 million in what can be called “goodwill,” another intangible asset. According to the filings, this is fully deductible.

SEC filings are not all growth; they also have to outline drawbacks: debts, legal proceedings, and other things affectionately-termed “asset impairments.”

Winn Correctional Center, which CCA returned to the State of Louisiana last year, would be considered one such asset impairment, highlighting one advantage private operators have over their public counterparts: a facility that can’t be made worthwhile in a business sense can be returned whence it came.

The difference between the public and private sectors are most obvious when it comes to employees. A large portion of the cost savings that privatized prisons can offer over public ones has to do with wages; private workers don’t get certain wage perks, but they do have access to some stock options to “encourage stock ownership through payroll deductions by the employees of GEO and designated subsidiaries of GEO in order to increase their identification with the Company’s goals a secure a proprietary interest in the Company’s success.”

The filings are pretty clear about the repositioning of incentives; financial ones can do wonders for identification with goals.

Read part 2 here.

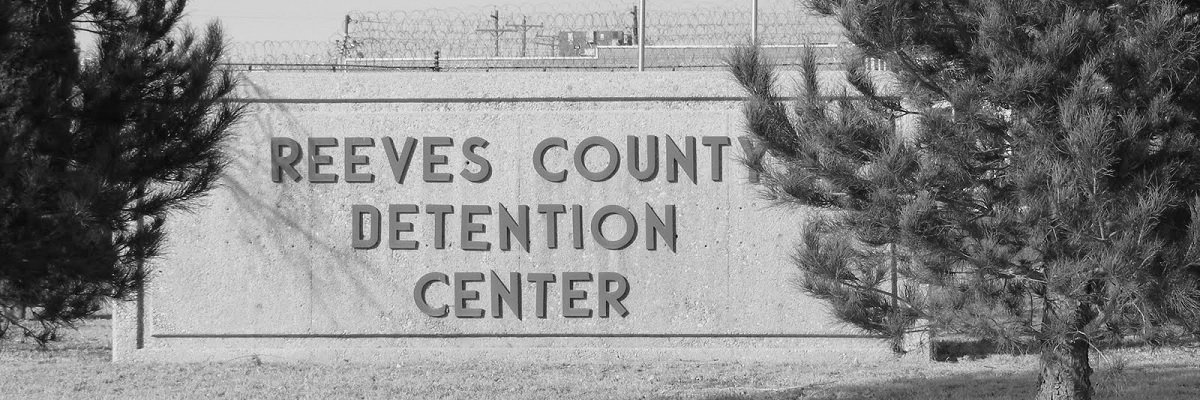

Image via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0