Read the first part here

If you’re interested in a public company, their Securities and Exchange Commission filings are an easy, obvious place to look for information. The SEC, as the federal division for stock market and securities oversight, essentially exists to protect investors from various frauds. As part of this mandate, public companies submit quarterly and annual reports, statements of their hopes and fears and the current state of things, meant to give shareholders, and the public, a sense of the kind of investment they’re making.

SEC filings can be pretty drab, and those of CCA and GEO Group aren’t so different on the surface. In addition to their annual 10-K and quarterly 10-Q reports, there are a swath of other materials they might have to provide: 8-K forms for major company events shareholders should probably know about, 11-Ks for employee finance plans, orders on public release of documents or shareholder resolutions.

But inside this unappetizing letter-number salad, as much can be made of what’s going on behind our national system private prisons as can be made of what’s on the forms.

Private prison companies realize they’re in a risky business, and they’re required to give investors the sense of that risk. As part of a recent securities notes offering, CCA enumerated the troubles of the trade.

Among these is the understanding, not new to private prison operators, that the communities in which they are being built might not take kindly to the idea.

CCA’s operation of South Texas Family Residential Center, for example, highlights multiple concerns, among them the appropriateness of kickbacks to towns that play host to a prison company. The management agreement is a modification on an IGSA between ICE and Eloy, Arizona, which receives a commission for the contract - the facility itself is in the Lone Star State.

And lawsuits, as they appear in SEC filings, discuss little specificity beyond the numbers. According to filings, CCA paid at least $1 million to the State of Idaho for their operation of the Idaho Correctional Center, which became known to the media at the “Gladiator School.” The fine would be considered an asset impairment, but the nature of disputes is largely irrelevant, although the implications of understaffing in a prison could have immediate fatal results.

The SEC isn’t tasked with judging the social merit of the markets; it’s tasked with making the markets work. The difference in goals is part of what makes the nature of private prisons so unsettling; each monetarily-incentivized step can be seen as contradictory to criminal justice as a rehabilitative mission.

For example, recent filings are encouraging their employees to get stock in the company to help align both parties’ goals. But this raises important questions about how that might affect disclosures of problems when many private prisons handle their own grievance processes. Theoretically, a worker, invested in the company, would be less likely to report a problem that might hurt his or her stock portfolio. This sort of intangible hypothetical is currently beyond the SEC’s dictate.

Remember Norman Carlson, the former skeptical BOP Director turned GEO Director? His transition to the private sector was perfectly legal. He spent 20 years with GEO Group. By the end of 2014, he was making $181,299 a year, plus stock.

Even in his retirement, he receives a retainer as Director Emeritus of $50,000 a year.

Private sector compensation packages destroy those of the public sector. And it helps to encourage the transition, which has been important to the success of both CCA and GEO.

Julie Myers Wood, former head of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the largest customer for privatized detention facilities, also currently sits on the Board at GEO.

After 30 years of decentralized protest to the use and growth of private prisons, CCA and GEO Group remain optimistic for their prospects, in part because of their healthy relationship with the federal government.

For CCA, ICE and the United States Marshals alone comprise 40% of their business, according to CCA supplemental shareholder materials.

Recent expansion by both CCA and GEO moves only to reinforce the ties. GEO’s acquisition of LCS brought under their umbrella the East Hidalgo Detention Center and the Brooks County Detention Center, among others.

As helpful as SEC filings can be, though, the privacy of the company will trump the public interest. Exhibit 2.1, cited above, was included with GEO’s filings for the period ending March 31, 2015; however, a separate decision, also publically available, contains a decision, made upon GEO’s request, stating that the actual agreement by which GEO purchased LCS would not be subject to the Freedom of Information Act.

So while SEC filings can provide insight that might be otherwise clouded, at least on the federal level, private prisons remain conveniently exempt from the Freedom of Information Act for many things.

With a system that seemed legally rushed through and a financial regulatory body that can’t control the human elements of economic success, we’re led to wonder: what exactly have we signed off on?

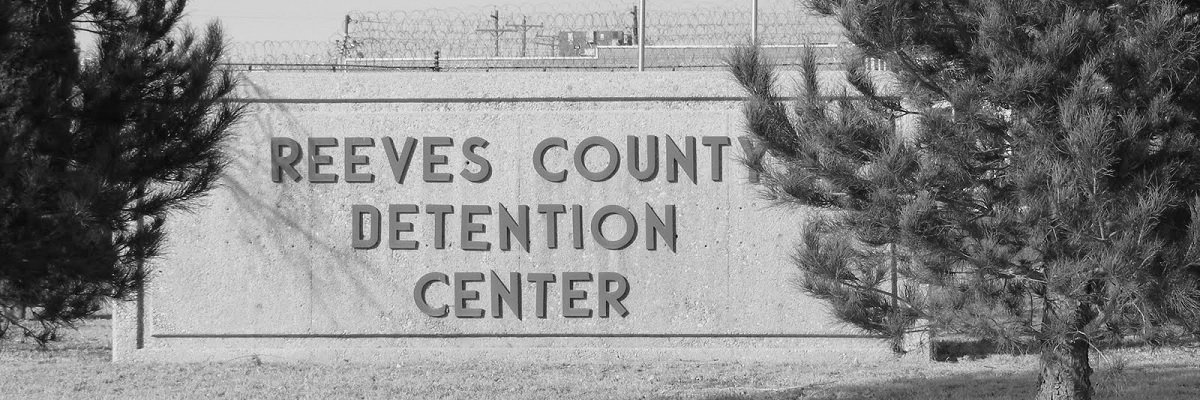

Image via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0