By now you’ve read that among its other systems-in-crisis, America’s correctional set-up is a sprawling, decentralized blanket of black holes that can’t help but breed sadness.

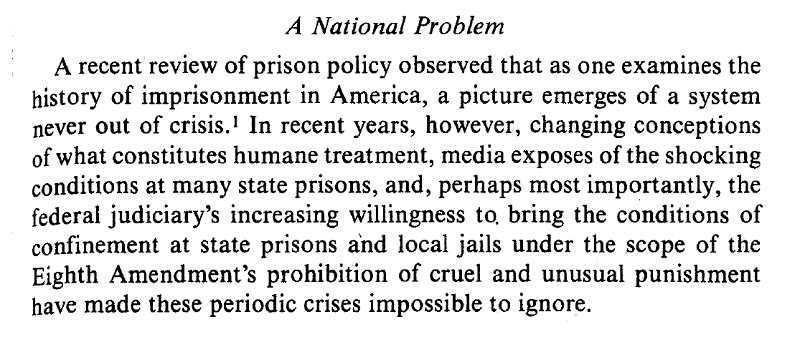

As familiar a refrain as it feels today, the clip above was written a generation ago, in 1986, as part of a Massachusetts Legislative Research Council report. The Commonwealth had passed legislation allowing contracting with private correctional firms, but it wasn’t sure that it wanted to follow up on the option. It was hard to say. There was much that they didn’t know.

It did cite, though, a 1981 National Institute of Corrections paper, which offered a tentative conclusion: it’s hard to knock it until you’ve tried it.

Ted Nissen, then-president of Behavioral Systems Southwest, summed up the alternative: “The work done in the public sector in the last 30 years has been a dismal failure.”

Another thirty years later, and Massachusetts has zero private prisons. Half of the United States, however, can’t say the same. It should be straightforward to evaluate the efficiency of this system at this point, but it actually is not. That, in turn, makes it difficult to evaluate the lines on which the option was sold in the first place. After a generation, the same answers to the same question feel less okay.

1. Private prisons are legal?

There are those that have found the very concept of for-profit prisons a bit creepy from the get-go, and the question of what right private operators have to hold inmates continues to bother people. It’s in part why Massachusetts decided against them. And it’s part of why politicians have latched onto the idea this election season. It’s a rare instance of politicians taking a look at a system as a whole and considering its abolition whole cloth, given that they actively enabled the sewing of that cloth in the first place.

Of course, there have been those outside of government, like the American Bar Association, that have long been wary of private prisons. But in the mid-eighties, legalization for the sake of court-ordered necessity seemed fine.

2. Aren’t the incentives misaligned?

It didn’t evade early skeptics that the money factor might influence how operations were run. Wouldn’t doing the government’s job at a lower cost necessarily mean cuts elsewhere? But proponents suggested that the incentives were clearly stacked to ensure better performance.

For one, prisoners would have more ability to sue a private prison than a public one. But all lawsuits were stemmed by the Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1995, and now private facilities handle their own grievance policies. When an outside observer asks for those, they often turn up blank.

All-in-all it’s interesting, because early arguments seemed to rely on the security provided by government and media oversight.

But even when government oversight is in play, the extent to which it’s effective is hard to pin down. A study of Mississippi facilities recently found that prisoners were being held longer in private than public facilities. A recent release of inspection materials related to the now-closed Mineral Wells Pre-Parole Transfer Center in Texas noted that improper procedures had been taken in administering disciplinary justice inside, where crimes mean time and time means money.

3. Can the private sector really do it better?

Competition breeds innovation, yes? But today’s private prison market is not a small and diverse - it’s vast and controlled by three - increasingly two - operators.

- Corrections Corporation - Red

- GEO Group - Blue

- Management and Training Corporation - Green

Early claims of “sophisticated management techniques” have only most obviously played out on the stock market and SEC filings. Other metrics of success - recidivism rates, education, and actual costs - are difficult to compare. And have been for the entire time private prisons have existed.

“In theory, comparing costs should be relatively straightforward and easy to accomplish, but in practice it has been difficult. Precisely how private firms have structured their facilities and at what cost is hard to learn because the details are often guarded as proprietary information. Governments’ expenditure reports are public documents, but the true costs of services are obscured by inadequate public accounting procedures, by the distribution of costs for services to more than one agency or to more than one account, and by the frequently deficient treatment of capital spending (such as failing to count the value of all physical assets used up during any year of operation). It is therefore surprisingly difficult to determine even so basic a cost as the average daily cost of an inmate’s imprisonment.” [Douglas McDonald]

The result has been something closer to a he-said, she-said approach to policy. Many influential early papers have since fallen into disrepute after their author was found to be on the private prison payroll. Government inquiries do the best with what they can. One study later commissioned from Dr. McDonald’s office by the Attorney General in 1998 relied on Department of Corrections officers responding to a survey. Varied reporting requirements based on differences in term definitions or areas does not lend itself to useful analysis. And, still today, no organized way of assessing private prisons’ success -particularly across regions - has been devised.

4. Won’t the workers be worse off?

Cost savings, upfront and today, have largely been attributed to personnel savings. Lower wages and private sector perks would cut costs for the government, the defense went, but would leave employees essentially the same. Unions like the National Sheriff’s Association and AFSCME have long been opposed to privatized facilities. Chronic reports of understaffing and high turnover suggest that a closer look should be taken.

5. What’s the alternative?

As it currently stands, the U.S. is in not so different a position as it found itself thirty years ago. At that time, and since then, private prisons have been used as the overflow release on public prison populations, meaning that efficacy concerns took backseat to immediate need. But back then it was sold as a potential example to be followed in the reconstruction of the whole.

Today, little fanfare is made of private prisons’ redemptive promise, and prison executives are still relying on America’s inability to come to terms with its justice system, alleging that so much political posturing cannot contend with the fact of our prison situation. But if states and counties continue to decide that they need extra help fast, they should start keeping and comparing numbers too.

Image by VOCAL-NY via Flickr and is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0