During the years it was operated by the private Management and Training Corporation, the “property” grievance was the most common type filed at Arizona State Prison - Kingman.

Over a third of the 3500-person facility’s 1600 grievances fell into this category, followed by healthcare (~450) and staff (~80) complaints; many more “Category 16” complaints would arrive after a “disturbance” last July. Case #M59-110-0**, initially filed three years ago this week, was among the seemingly more benign complaints filed in the time before riots shook the prison and management was changed. The issue was a missing pair of shoes.

The V4orce Nitrus men’s running shoe was one of four sneaker choices inmates had inside. According to Inmate 2*3*9*, they were the cheapest and the best looking option; he’d already had one pair and in late May 2013, while he grabbed some strawberry cheese danish ($0.98) and another antishank toothbrush ($0.04), he ordered a new set ($17.98), which he’d be able to pick up from the property office in a week.

Image via Ebay

Public and private prisons across America receive thousands and thousands of grievances, formal and informal, each year. And it’s only once all administrative grievance procedures have finally been exhausted that an inmate can take a case to court, a measure implemented in the mid-nineties via the Prison Litigation Reform Act, effectively meant to keep their complaints getting too much play.

When it went into effect, prisoner suits made up 15% of all federal court filings, and their high rate of dismissal seemed an indication of their lack of legitimacy. Imagine it as something akin to the worst attitudes taken toward FOIA and public records requests: to stem the tide another bureaucratic hurdle is added with public interest dismissed on technical grounds.

Add it to the list of ways the inmate in the United States is a sort of sub-American, currently the largest category of second-tier citizen, barred from voting, publishing, and the prohibition of slavery. They’re squeezed financially for everything from food to phone calls by everyone from the major corporations trading on Wall Street to the very neighbors that share their communities. Their failures in court before the PLRA, and even now, are often to do with a lack of legal-level literacy or representation, rather than common sense merits. Nonetheless, inmates must now take their grievances to the formal end of the internal system before they can take their problems elsewhere.

Inmate 2*3*9*, for one, never received his sneakers.

According to the back-and-forth included in a batch of formal grievances obtained via public records request, his scheduled pick-up time of 9 a.m. on May 30, 2015 came and went without him, because he was at work at “Wheels of the World,” an inmate work program.

“Property doesn’t make exceptions to pick it up,” he wrote in one appeal, “you get your property at the hours property is open.”

And, ultimately, after multiple appeals, the grievance was denied.

Prisoners and their plights have been punchlines far longer than popular talking points. The seriousness of conditions as a whole can go missing in the disconnect between everyday issues like shoes and more violent problems. When Senator Robert Dole introduced the PLRA, he relied on the laugh factor to prod people to support it.

As Chief Justice William Rehnquist has pointed out, prisoners will now “litigate at the drop of a hat,” simply because they have little to lose and everything to gain. Prisoners have filed lawsuits claiming such grievances as insufficient storage locker space, being prohibited from attending a wedding anniversary party, and yes, being served creamy peanut butter instead of the chunky variety they had ordered. - Bob Dole, May 25, 1995

Meanwhile states were passing laws that would contribute to the larger-than-ever population we have now.

The popular dismissal of the peanut butter incident overshadowed opposition to the bill; Senator Edward Kennedy for one called the bill “patently unconstitutional.” It was cosponsored by an Arizona senator whose appreciation for the accuracy of estimates has since been called into question. The very fact that sometimes their complaints are legitimate and en masse can help point to larger problems within the facility had little room in a legal system burdened by its own inefficiency.

As Inmate 2*3*9* stated in his appeals, and maintains until this day, he never received those sneakers. The inventory form the decision relied upon, he claims, was signed by someone else, forged, maybe, by another inmate, and the sneakers they said were found during a cell search of his room on November 1 were, according to him, his older pair.

None of it much mattered after the request was denied, and his story remains unchanged. “I did complain about a pair of shoes,” he says. “I never got them.” Since he was released at the end of last year, he’s taking it a day at a time, he says. The missing prison shoes are a thing of the past, a future with children and his girlfriend occupying his present. Still, not every grievance has an all’s-well-that-ends-well finish, not even for him, when there was disgruntlement throughout the facility. He was watching television and waiting for permission to call home when the riots at Kingman began.

Prison riots are the most extreme expression of communal displeasure the incarcerated can really muster, and at ASP - Kingman, employees later expressed no surprise at the tension that erupted in early July 2015. In addition to the injuries sustained by both inmates and employees, the total costs included the need to move over a thousand inmates from the near-destroyed units, the deployment and destruction wrought by tactical units called in to quell the disorder, and the dissolution of the MTC contract in favor of new management under GEO Group. One of the guards involved was even moved to take his own life.

From hawk-eyed hindsight, maybe we can say that the signs were there all along, in things like the common chance your packages will never arrive. But if that’s the case, why don’t we see them beforehand?

Lawsuits have dropped in the years since PLRA was enacted, indicating that it’s been successful at stymieing those many complaints. It’s three strikes provision, barring court filing fee waivers for inmates who have had three previously-dismissed cases, is up for debate soon.

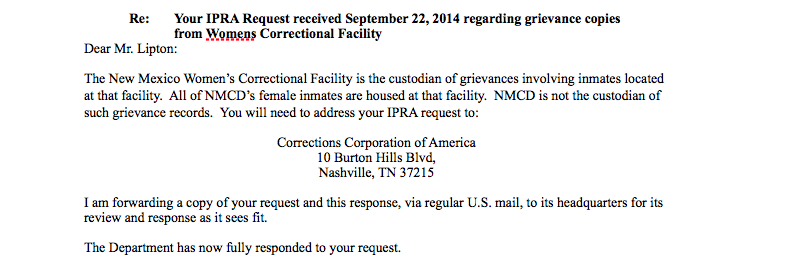

That being the case, inmates must go through their facility’s internal grievance procedures, which can be the sort of paperwork knot that we’ve come to expect from our government bureaucracy. Each state - except for Alabama - currently has some standard operating procedures by which inmates can submit grievances. This typically includes a series of formal and informal procedures and appeal steps.

Just as it can be frustrating to get a grievance submitted, for journalists and researchers on the outside, access to a meaningful understanding of prison complaints is also a challenge. With so many complaints kept in so many different files, access to copies is quickly cost prohibitive, even if one can narrow the search to a particular subset. By policy, most grievances are handled internally, at the most local, informal level, if possible, with a formal grievance and appeals process available, meaning that in many cases, accountability is conducted and correlated by the accused parties themselves.

This has its roots in the practical - how many resources can be spared to investigate - but becomes more problematic when applied to private prisons, like Kingman, where incentives do more to encourage grievance dismissal than deterrence. In the majority of states hosting private prisons, grievances are, by policy, handled internally as they are in Arizona.

That leaves a lot up to the discretion of the facility, which, given that the annual inspection only includes two points about inmate grievances, assumes a lot about private prison scruples.

When there’s no real way to effectively grieve about the grievance process, a protest of sorts can seem like the only chance to affect change on the situation in a liveable amount of time. Even cases that successfully find their way into the courts - such as Brown v. Plata, which deemed unconstitutional the conditions created by California’s overcrowded system - can take decades to run their course. From outside, it becomes obvious that the walk in a prisoner’s shoes is not so simple when it’s much easier to just take them.

Check back in on Thursday for Part 2, in which we’ll discuss the process of inmate grievances and the options for getting to them.

Image via Arizona Department of Corrections