Read Part 1 here

On July 1, 2015, inspection reports suggested maybe-even-better-than-usual business at ASP-Kingman. The Hualapai Unit was operating at “Excellent” levels in the categories of “Staff Appearance,” “Staff Morale,” and “Professional Behavior”; “Inmate Morale” was consistently labeled as “Adequate.”

And yet the next day came the first in a series of back-up calls made to the Mohave County Sheriff’s Office.

By July 4, Independence Day 2015, inmate unrest in the Cerbat and Hualapai Units had grown to riot levels, ultimately requiring deployment of special tactical units. The inspection reports had pointed to other areas where the prison was consistently noncompliant, particularly in the areas of access to medical care, and noted multiple vacant positions impossible to fill with a short staff and available extras already working overtime, an echo of the staffing insufficiencies that permitted the dramatic escape of two inmates in 2010.

But despite the regular inspections and the glimpses of frustration that found their way via inmate grievances to the administration, the prison and DOC officials were unprepared for the outburst and destruction of the facility, which required the relocation of most of the units’ inmates.

Nearly every U.S. state Department of Corrections has implemented its own grievance procedures - for the most part, these apply in the same way to the prisons, both public and private, being operated under the jurisdiction of that DOC. The hope of the majority of these is to handle inmate problems at the lowest level possible, within the unit or the prison first, before moving the complaint further up the line; sexual assault issues are allowed a more direct process care of the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), and other types of complaints may have their own specific grievance or appeal procedures.

But, for the most part, grievances start as close to the unit as possible, and this can present a problematic state of affairs at privately-operated prisons, where successful grievances can suggest inadequacies worthy of criticism and retributions, financial and otherwise.

There are typically two levels of grievance - informal and formal - and an inmate must go through the full process before they can turn to judicial options. Failure to follow time deadlines or other parameters can result in an automatic dismissal.

For Inmate 2*3*9*, this meant first an informal complaint on Form 802-11.

The informal response stating that his shoes had been found and they’d be sent over was returned on Form 802-12(e).

Then began the formal process. He immediately filed a formal grievance, Form 802-1, restating his complaint.

About six weeks later, he received a confusing response, stating that both reimbursement would not be recommended and that his request had been approved.

He followed up with a formal appeal, Form 802-3P, on September 3, 2013, which was denied on the eighteenth by the DOC’s Deputy Bureau Administrator.

His next step was to appeal Warden Rider’s decision to the Director of the DOC, which was submitted on October 10. On November 5, the process was closed with a letter signed by Charles Ryan stating that no further action would be taken.

One can see the appeal of keeping complaints close to home. By the time the complaint had gotten out of the unit and to the warden, prison officials needed to rely upon the paper trail available - the property receipt - which was signed, though, the inmate maintains, not by him. And while one can imagine the built-in frustration of the process altogether, it’s also hard to imagine a more straightforward way.

What can be left to be desired is a better way of actually looking at, considering, and correlating those complaints.

The grievance from Inmate 2*3*9* was provided by the Arizona DOC in response to a request for two-months worth of formal grievances.

Seven were returned, a clear fraction of total grievances that were submitted to the facility, most of which never created an initial paper trail, and the inmate’s informal submission was only included as part of the file.

With summer upon us, it’s important to consider that the riots always seem, in retrospect, to be expected. Just last year it was ASP-Kingman, Willacy County Correctional Institution, Cimarron Correctional Facility. In none of these cases were the displeasures of inmates unknown. So why didn’t the grievance process, meant as an outlet for such tension, treat some of the problems?

This inmate’s grievances were only a sliver of the total grievances that are submitted each year; most, it seems, don’t receive appeals, a common characteristic across the board. And for the interested, there are common barriers to access at both public and private prisons.

For example, the practice of keeping the only copies of informal grievances in inmate files makes collection and reproduction at Kingman, like at other prisons, informal grievances are kept in individual files. After the riot, inmates were moved to other prisons, and the process of searching for all of the files would require tracking down everyone who was moved out, a nearly impossible use of time and resources, already a burdensome task even if all inmates who had made a complaint were within a prison.

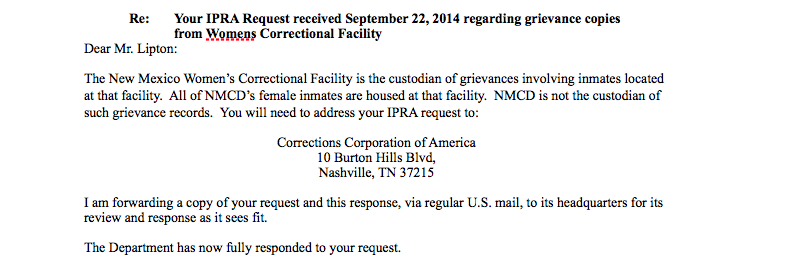

Simply asking the DOC for copies of grievances, particularly from private prisons, is typically unsuccessful, because they’re handled internally, and that’s the case in most places.

A request to the New Mexico Department of Corrections resulted in a check being sent to the lawyers for Corrections Corporation of America and pages of redactions.

Other options do exist, however, for finding out what’s going on. For one, grievances logs can give you a sense of scale when it comes to total numbers across categories. In Arizona, grievance logs are kept by month per unit, a sort of index of what came through formally. Alternatively, one can look at a particular subset: only formal complaints or only cases that have been appealed, for example.

But what consistently exists is the sense that accountability measures are implemented with the nominal purpose of keeping things copacetic. A prison rebrand doesn’t necessarily mean a whole new set of staff or effective policies.

In fact, the latest news from Kingman suggests that to make matter more comfortable for GEO Group, the state may be looking to lighten the burden on the operator.

Which is why attention on the local level is important to keeping prisons across the country accountable. And a good place to start would be listening to the ones inside.

Want to help prisons, public and private, stay accountable for their actions? Have a grievance you’d like heard? Let us know at info@muckrock.com and we’ll submit requests on behalf of you or your loved ones for materials on a prison near you.

Image via Arizona Department of Corrections