A version of this article appears on Glomar Disclosure

In 1976 and again in 1977, the Justice Department decided not to prosecute anyone for the CIA’s illegal surveillance and mail openings. The report issued in 1977 reveals the Justice Department’s highly flawed reasons, including claims that prosecution would not serve to prevent such questionable or outright illegal surveillance from happening again - ironically setting the stage for modern surveillance programs.

The 57 page report begins with a surprising assertion – the Justice Department disagreed with everyone about the mail opening program being illegal. According to the Justice Department, “it would be mistaken to suppose that it was always clearly perceived that the particular mail opening programs of the CIA were obviously illegal.” Saying that they disagreed with everyone is not hyperbole – even CIA admitted that the programs were illegal.

However, it was well documented at that point that the programs were illegal, and even those carrying out the programs believed so. Specifically, both the Directors of both the FBI and CIA submitted a document in 1970, three years before the programs were officially terminated, stating that the programs were illegal. Several days later President Nixon withdrew authorization for the programs, which continued nevertheless. As noted by the Church Committee, “Throughout [the 20 year] period CIA officials knew that mail opening was illegal, but expressed concern about the “flap potential” of exposure, not about the illegality of their activity.”

Most unforgivable is the fact that this is one of the reports cited by DoJ in their decision not to prosecute anyone at CIA. This knowledge didn’t prevent the report from calling the knowingly illegal, premeditated decisions by CIA as “good faith mistakes or reliance on the approval of government officials with apparent authority to give approval.” The best that DoJ could claim, based on this, was that some CIA officials believed the programs were legal and authorized. The same cannot, however, be said for the people running the programs or for CIA Director Helms or FBI Director Hoover. Moreover, the DoJ already had testimony from the CIA officials running the programs wherein the officers acknowledged knowing the programs were illegal.

One of the Justice Department’s most egregious reasons for not prosecuting CIA is because it was partly the fault of the Justice Department, and so prosecuting CIA “[would take] on an air of hypocrisy and may appear to be the sacrifice of a scapegoat.” The report does not discuss the possibility of resolving this potential hypocrisy by prosecuting or further investigating anyone at the Justice Department for these failings.

The Justice Department was very quick to claim that, with one exception, the projects were outside the five year statute of limitations that would allow them to prosecute. This statement was deliberately disingenuous and misleading on several points. Most significantly, the report acknowledges elsewhere that if any of the acts that were part of a conspiracy were committed within the last five years, then the entire project and conspiracy can be indicted.

The significance of this cannot be overstated, as it not only would have allowed the Justice Department to prosecute for the entire “East Coast Project” but for the “West Coast Project”, also known as Project WESTPOINTER, as well. The Justice Department became aware of Project WESTPOINTER within the five year statute of limitations, and submitted their first recommendation not to prosecute for Project WESTPOINTER before the statute of limitations had passed. project-westpointerIn other words, recommended that there be no prosecutions for Project WESTPOINTER, waited until prosecution became impossible, and then used that impossibility to justify not prosecuting anyone for Project WESTPOINTER.

In order to justify not prosecuting former President Nixon or the Directors of the FBI and CIA, the Justice Department had to tell an outright lie – that they had “no direct evidence which suggests that former President Nixon was ever specifically informed of the mail opening projects.” This is simply not true. From the Church Committee report, published before the Justice Department first officially decided not to prosecute anyone and referenced in this report:

As to whether the President could even authorize such a program, the Justice Department says it best.

According to the Justice Department, one reason the mail opening program might not result in convictions was because “those who send or receive mail crossing the border of the United States do not enjoy the same expectation of privacy as those sending or receiving domestic first-class mail.” The Department explained that “The expectation of privacy in the contents of international mail therefore cannot easily be equated to-the expectation of privacy in domestic mail.” This sentiment has cropped up again and again in mail intercept programs, particularly for modern electronic surveillance.

On an interesting note, the Justice Department explained that one reason the expectation of privacy is different is because customs officers are entitled to open international mail to look for pornography.

The most important quote, however, comes at the end where the Justice Department declares that the idea of free speech itself may not apply to international communications. “The international exchange of ideas, especially with citizens of potentially unfriendly powers, may be on a different footing from the domestic exchange of ideas.” Significantly, the Justice Department didn’t limit it to “unfriendly powers”, but instead used the broadest interpretation possible – “potentially unfriendly powers.”

The report ends by arguing that prosecution wouldn’t effectively ensure there wouldn’t be illegal surveillance in the future.

However, in light of that sentiment, one has to wonder how the NSA surveillance programs would have developed if there had been prosecutions.

Would the Patriot Act have been examined more closely? Would CIA and NSA made sure Congress was more aware of and better understood their programs? To a degree, it’s almost certain. Instead, the Justice Department opted for better legal structures and institutional changes – something we’re still struggling with nearly forty years later.

Had the Justice Department decided to prosecute, we would be looking at a very different world today. Even a failed prosecution would have sent the message that the potential for legal consequences was there. Instead, it reinforced the attitude of some in national security circles that they didn’t have to worry about the legal ramifications – only a public relations “flap.”

It’s a mistake the Justice Department seems to keep making – but it doesn’t have to.

Read the full report embedded below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

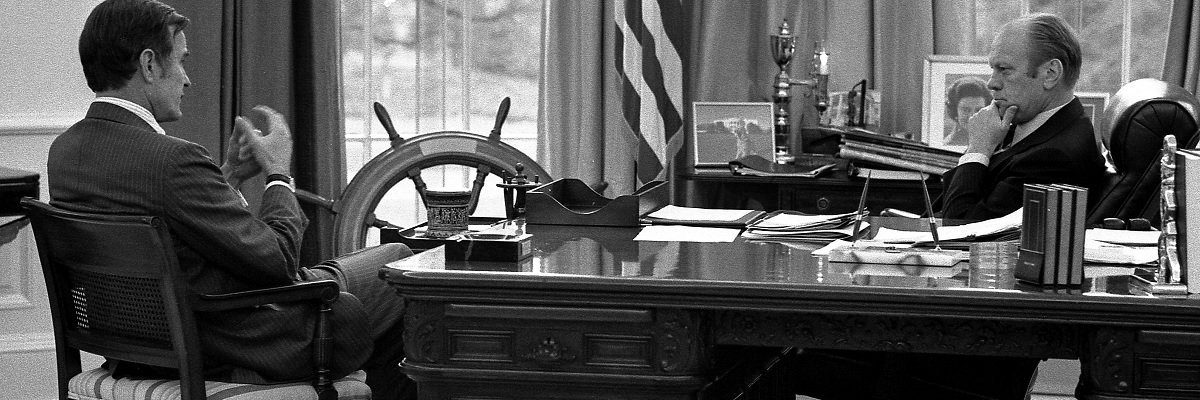

Image via Wikimedia Commons