Responding to our recent request for mobile phone forensic tools records, Denver Police Department has provided us with not only contracts, but a training bulletin for their Cellebrite Universal Forensic Extraction Device. Cellebrite’s UFED, as the device is more commonly known, is the leading model of mobile phone data extraction tools in law enforcement.

Denver PD purchased a UFED Touch in January 2016 for about four grand. The Touch is used for cell phone data extractions done in the field and was infamously rumored to have been used by the FBI to crack the San Bernardino shooters’ encrypted iPhone after Apple denied their request for access. DPD also purchased a UFED 4PC for $1,650 - the 4PC is more of a software program to sift through data already collected on the Touch.

That Training Bulletin we got does a fine job of explaining just how potent these devices are and how they are used.

It has been reported over the last year or so that Cellebrite couldn’t hack into the iPhone 5c used in San Bernardino, due to passcode encryption for models after the iPhone 4 not being offered yet. This however, is no longer true, as the company’s website and an October 2016 article in The Intercept reveal. All that data is very much in range of these devices on most iPhones and other cell phone models.

Of course there may be easier ways to unlock a phone - in the bulletin DPD instructs any officers operating a UFED to “obtain a password or passcode from a locked device if possible.”

It is entirely unclear how this is accomplished, and it seems like this might have warranted some of its own guidelines. If all else fails, they can always send the phone to the Rocky Mountain Regional Computer Forensics Lab to see if they have the right tool to crack it.

DPD’s Investigative Technology Bureau has plans for just about any eventuality in fact, with rules ordering the battery be removed to guard against remote data deletion, all chargers and wires be seized with the phone, and perhaps the most important of all: don’t start digging through the phone on your own because it is a) illegal and b) you are gonna destroy evidence.

One would hope not tampering with a crime scene would be more or less common sense to professional law enforcement, but always good to make sure.

Over half the bulletin is devoted to the legality of data extraction; as is noted in these records, the 2014 Supreme Court case Riley v. California set down some strict precedent for law enforcement concerning the search and seizure of mobile phones and computers. Basically, it is the same idea as the searching of a house, in that a warrant is gonna be involved one way or another. Exigent circumstances are allowed, though they are subject to automatic judicial review and must be used only in matters of absolute life or death, like kidnappings or bomb threats. With devices as powerful as the UFED, and with a company as resourceful as Cellebrite, tough standards need to exist on utilization.

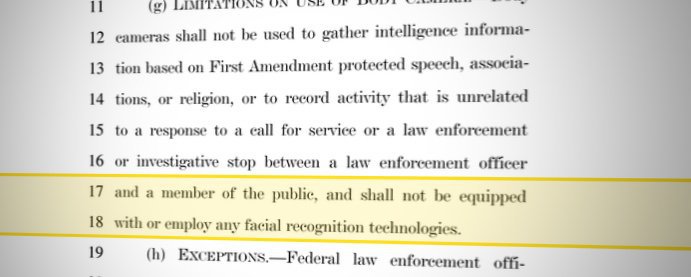

Denver Police are also “currently evaluating the efficacy of utilizing facial recognition software,” which we learned from another recent records request. The agreement with Ideal Innovation Inc. for their Facial Automated Biometric Identification System Mobile (FABIS-Mobile), which uses an app on Android phones or tablets to connect to a larger database of between one million, twenty million, or potentially a billion faces to instantly identify in the field.

It is unclear how long the trial runs for, but it was signed December 2, 2016 and DPD informed us it was ongoing. The agreement is vague and doesn’t say anything about the legality of its use or other topics that might be important for us to understand how police use facial recognition software and what the limits are on its use.

Read the full training bulletin embedded below, or on the request page.

Image via Bahrain Watch