One of the documents released by the FBI is both redacted and very blurry, making it difficult to read. For clarity and ease of reading, some excerpts below instead reference an original, unredacted and far more legible copy of the same document.

While popular media has often portrayed Jim Garrison, the New Orleans District Attorney behind the infamous Clay Shaw trial, as having been targeted by the federal government for retribution, a look at his FBI file reveals the exact opposite - according to the documents, Garrison’s investigation was considered so toxic and aggressive that Director J. Edgar Hoover ordered no agents have any contact with him. When third parties began providing the FBI with evidence that Garrison had engaged in fraud against the government, the Bureau cautioned against investigating him, precisely because of how Garrison would inevitably frame it.

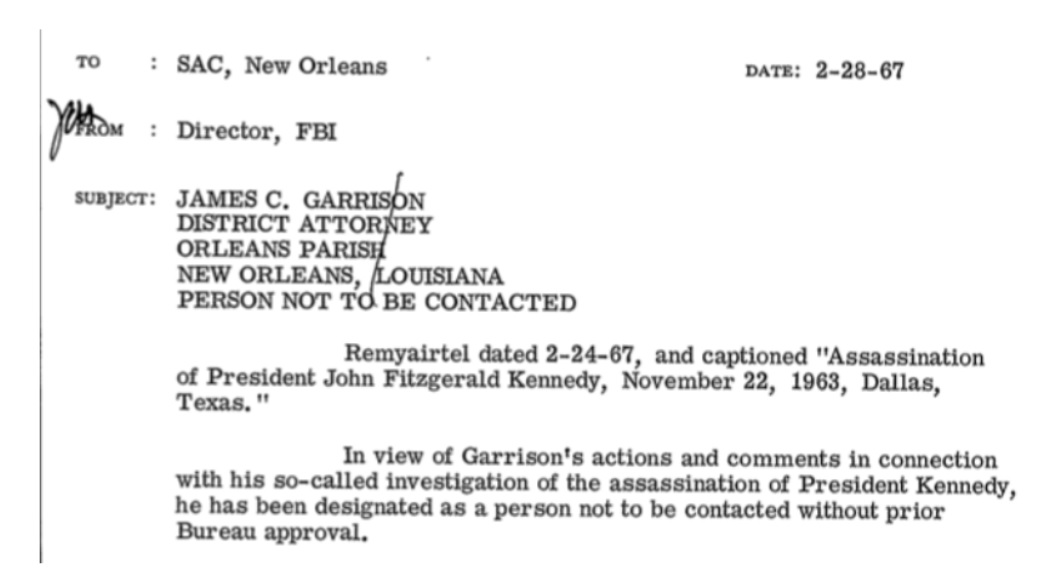

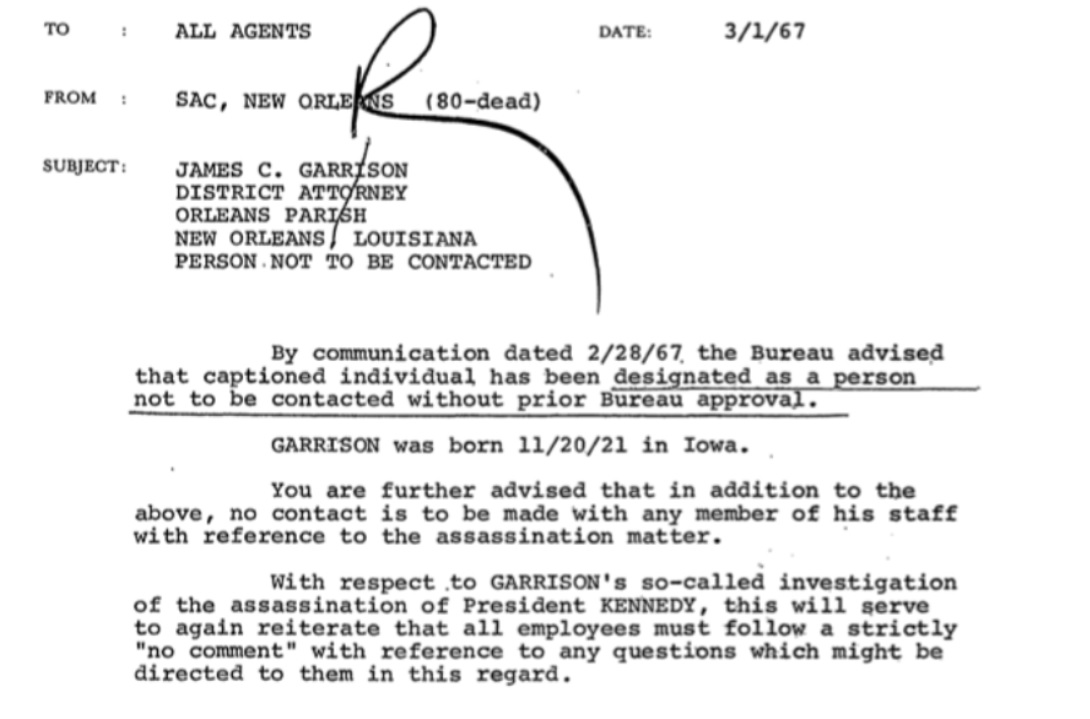

As early as February 1967, the FBI Director had ordered the Bureau’s agents to avoid all contact with Garrison and his investigators. Just days before a KGB planted story would appear in the Italian newspaper Paese Sera and redirect Garrison’s investigation to obsess over CIA connections, Hoover identified Garrison as “a person not to be contacted without prior Bureau approval.” This was the explicit result of Garrison’s already inflammatory investigation and accusations.

The next day, the Special Agent in Charge for New Orleans dutifully passed on the instructions, adding that no member of his investigation’s staff was to be contacted nor were any Bureau personnel to respond to the media with anything more than “no comment.”

Aaron Kohn, who headed the Metropolitan Crime Division in New Orleans, was positioned to keep his ear to the ground and report to the FBI. According to an FBI document dated May 5, 1967, Kohn provided the Bureau with information about Garrison’s activities, his wrongdoings and a heads up about pending publications. The day before the document was written, Kohn had informed the Bureau that Newsweek was going to publish an article about Garrison’s investigation, detailing attempts by Garrison’s staff to intimidate witnesses. Kohn’s information was completely correct with only one minor error - the Newsweek article was published a week later than he predicted.

According to Kohn, whose version of events would be confirmed by other investigators and an audio recording, Garrison’s investigators’ had attempted to bribe a potential witness into providing false testimony. As on part of their effort to get what would appear to be incriminating evidence against David Ferrie included an attempt to bribe Alvin Beaubouef, “a close friend of Ferrie” to provide false testimony.

When the investigators were tricked into allowing themselves to be recorded while repeating their offer, they apparently returned to threaten Beaubouef into signing a statement that the offer was not a bribe.

The tape recording, the contents of which would be confirmed by multiple witnesses, leaves little doubt, however. “Well, he can’t fill in the missing links if … he doesn’t know. And that is what the deal is predicated on.” In that investigator’s own words, “we could put $3,000 on him just like that [snaps his fingers], you know … I’m sure we would help him financially and I’m sure … real quick we could get him a job … Al said he’d like a job with an airline and I feel the job can be had, you know.”

Regardless, the issue was not a federal one and the tape was provided to another local District Attorney who would later confirms its contents to the Bureau. According to Kohn, however, this was not the only threat that Garrison had apparently responsible for. Carlos Quiroga had apparently reported that Garrison had told him his life would be in danger if he didn’t testify for Garrison. When called to testify before the Grand Jury, Quiroga repeatedly stated he’d been threatened with perjury if he testified.

Quiroga’s accusations were similarly out of the Bureau’s federal jurisdiction - but one accusation relayed by Kohn wasn’t. According to Kohn, Garrison claimed to have resigned from the National Guard as an alternative to facing military charges. Garrison had reportedly falsified his drill duty certifications for roughly six months, resulting in fraudulent pay from the government.

This, as noted by an earlier memo, fell fully within the FBI’s jurisdiction.

Nor was Kohn the first person to provide them with this type of information. The Bureau had previously received similar reports from the district director of the U.S. Customs Service in New Orleans.

After the Bureau received the initial report from Huff, they referred the matter to the Assistant Attorneys General of the Criminal Division and the National Security Division, apparently without highlighting the possible fraud violation. The only comment the Bureau apparently offered was that any investigation of Garrison was likely to be presented by Garrison as the FBI attempting to interfere with his investigation.

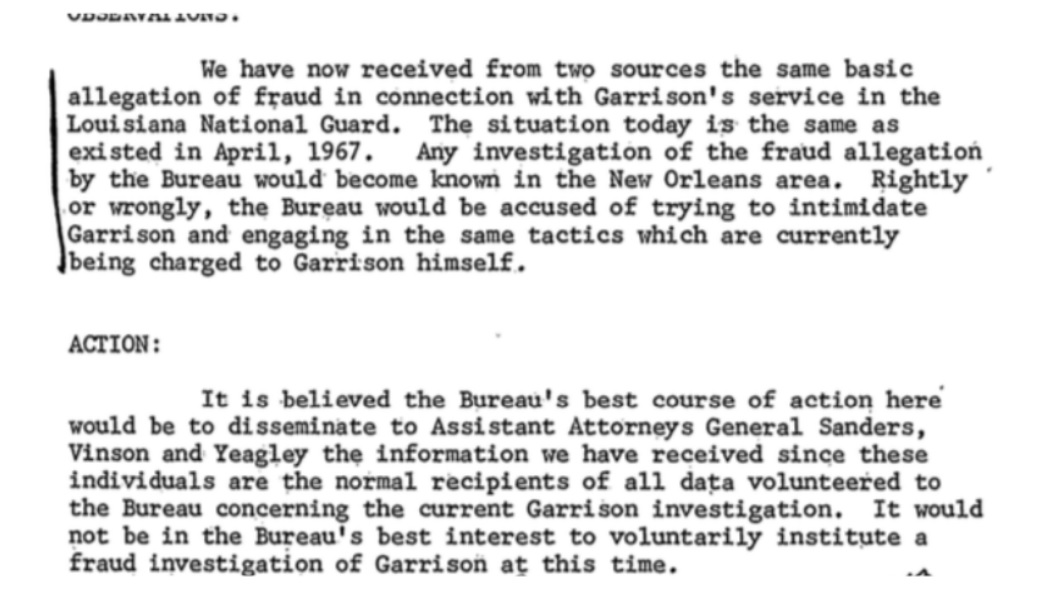

When the Bureau received a second report that seemed to corroborate their initial source, they decided that nothing had changed. If they attempted to investigate Garrison, it was inevitable that it would become known in the area and word would leak to Garrison. “Rightly or wrongly, the Bureau would be accused of trying to intimidate Garrison and engaging in the same tactics which are currently being charged to Garrison himself.” As a result, the Bureau concluded that it wouldn’t be in their best interest “to voluntarily institute a fraud investigation of Garrison at this time.” Instead, they simply referred the matter to the Assistant Attorneys General again.

Years later, Garrison would be swept up in an organized crime and gambling probe. Unlike the prior fraud allegations, these didn’t center on Garrison exclusively. Two New Orleans police officers “and seven other persons” were arrested as a result of a months long investigation which was summarized in a 113-page affidavit and supported by tape recordings. For his part, Garrison had long argued that there was no such as the mafia and nothing wrong with him receiving gifts from those associated with the Marcello crime family.

You can read part of the FBI’s release below, or the rest on the request page.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Warner Bros