When I asked the North Dakota State & Local Intelligence Center (NDSLIC), the state’s fusion center, for their threat assessments compiled during the Standing Rock NoDAPL protest movement, I was expecting more than a measly two assessments. Further, these threat assessments are stunningly similar to one another. In fact, it seems that the threat assessment from October 20th 2016, a little more than a month after the preceding September 8th report, added nothing more than a couple pieces of intelligence.

Don’t take my word for it, just look at the records below:

Given more than a month the fusion center managed to gather a few more reports of law enforcement arresting water protectors who had locked themselves to construction equipment in a sleeping dragon maneuver, and a report of Green Party 2016 presidential candidate Jill Stein arriving at the protest.

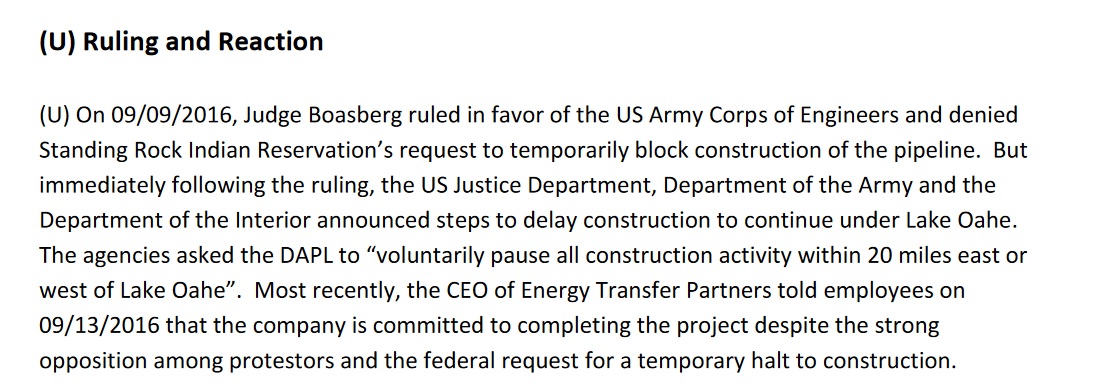

And despite their warning in the September 8th threat assessment, repeated in the October 20th version, that there was a “high threat of violence” if Judge Boasberg did not issue an injunction against the Dakota Access Pipeline, their follow up on this is more concerned with the Obama administration’s ultimately toothless request to Energy Transfer Partners to “voluntarily” cease construction on the pipeline.

No mention of violence, most likely because there wasn’t any.

What these threat assessments are most indicative of is that fusion centers are not very good at their job, do not produce intelligence which is actionable or particularly useful, and are instead used to gain intelligence about activist groups, and other members of the public who are not a crime risk, violating their civil liberties for basically no reason at all.

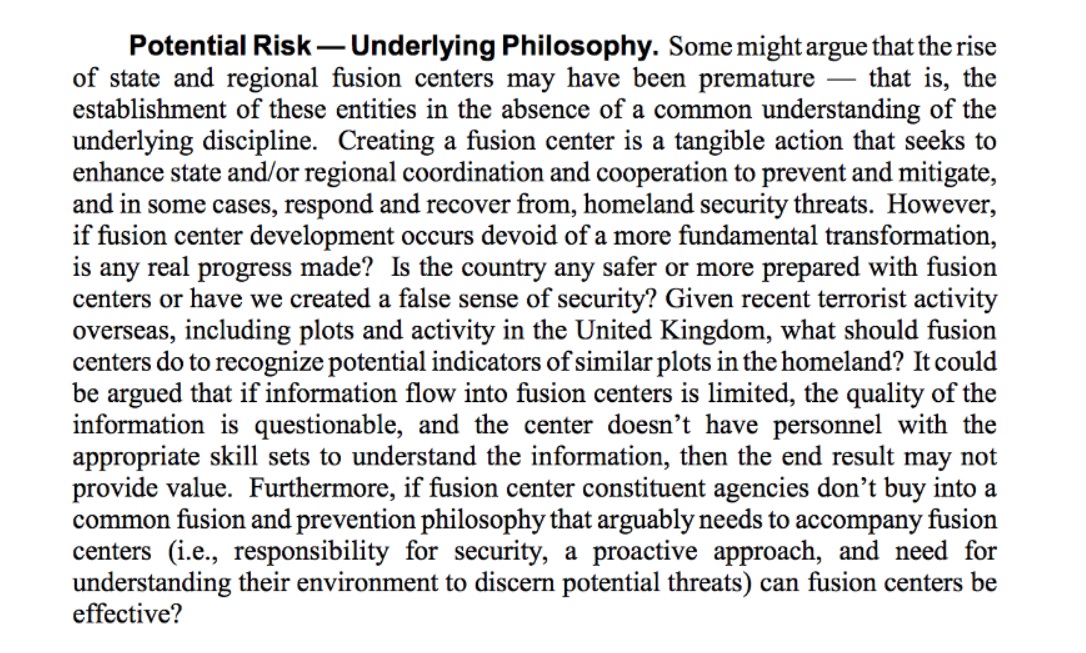

In 2008 the United States Congress published a report on the efficacy of fusion centers, which were originally set up after 9/11 to gain intelligence about possible terrorist threats. The report is not particularly charitable. On the list of “Potential Risks for Fusion Center,” number one is the “Underlying Philosophy.”

Make sure to note the bit about the “establishment of these entities in the absence of a common understanding of the underlying discipline.” For this report, fusion center workers around the country were interviewed - if one of the takeaways of this report was that there is not a common understanding of what a fusion center even among staff, that is a huge problem when fusion center staffers are doing the kind of “pre-emptive policing” that can easily infringe on civilians civil liberties.

Which brings us to the next potential risk, “Civil Liberties Concerns or Violations.” Take this part:

Following this, the report makes reference to concerns of civil liberties advocates who feel that this kind of pre-emptive policing can frequently lead to “unlawfully gathered intelligence,” because as they put it the intelligence was gathered without “criminal predicate.” Fusion centers don’t require warrants to do a massive amount of intelligence work on in the interest of identifying threats before they happen. There is a strong argument that more or less, fusion centers may be an illegal source of intelligence. To quote the report, “Furthermore, it could be argued that one of the risks to the fusion center concept is that individuals who do not necessarily have the appropriate law enforcement or broader intelligence training will engage in intelligence collection that is not supported by law.”

And as the ACLU put it, “We are granting extraordinary powers to one agency, without adequate transparency or safeguards, that hasn’t shown Congress that it’s ready for the job.”

While the report mentions a few standout fusion centers which have coordinated with local civil liberties advocacy groups to make sure they adhere to stringent standards, most cited lack of funds in being able to train for civil liberties awareness and for being able to coordinate public relations meetings with activist groups. The section of the report ends with some very valid questions.

The problems with fusion centers extend to their very structure.

What this means, is that a fusion center are subject to oversight not from the state or municipality that it was created in, but from the state and local law enforcement agencies that staff it and contributed to its creation. This is obviously problematic with this kind of wide net policing, when focused oversight is very much needed to prevent civil liberties violations or worse.

Perhaps the most worrying of the issues that the report identified, was the fact that fusion centers are not actually very effective. While fusion centers are supposed to be a new form of “proactive policing” that will stop crime before it happens, there doesn’t seem to be any actual analytical process. Instead, fusion centers sift through huge dumps of intelligence by state or local agencies. As the report identifies, “Most fusion centers respond to incoming requests, suspicious activity reports, and/or finished information/intelligence products. This approach largely relies on data points or analysis that are already identified as potentially problematic. As mentioned above, it could be argued that this approach will only identify unsophisticated criminals and terrorists.”

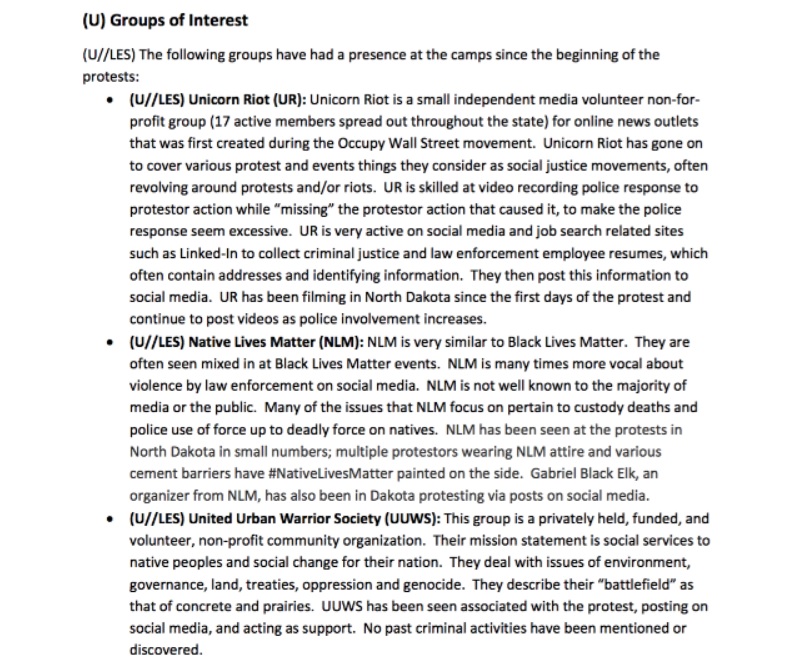

What the NDSLIC Standing Rock threat assessments illustrate is the futility of these kinds of operations. While nothing particularly useful was gained from the surveillance and intelligence gathering, activist groups like Indigenous Environmental Network, Native Lives Matter, Urban Native Era, Honor the Earth, and even the journalism outfit Unicorn Riot were nonetheless caught up in a massive intelligence dragnet.

These are groups of non-criminal citizens who are not a threat to anyone’s life or livelihood. But they are nevertheless targeted for surveillance and intelligence gathering by this fusion center and listed as “Groups of Interest.”

Read the full report embedded below, or on the request page:

Image via Kentucky Department of Homeland Security