Read Part 1 here

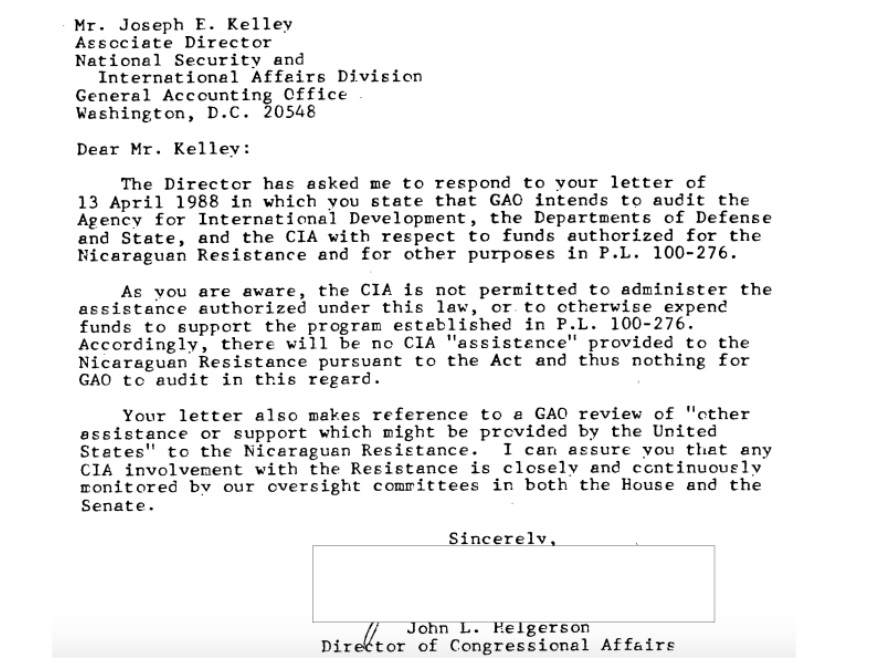

The 1988 amendment was especially alarming to the CIA Director, because it included the possibility that the GAO would be able to sue over information. Their letter argued that the mere prospect of a lawsuit presented “a substantial danger of unauthorized disclosure.”

While Iran-Contra provided fresh insight into the inadequacy of the situation, it nevertheless failed to produce any meaningful change in regards to GAO. At least one Iran-Contra related GAO investigation was hampered by the fact that the GAO was denied certain documents until after their report was issued. The eventual release of these materials substantially changed the GAO’s conclusions, as they provided the evidence GAO needed to conclude that lobbying statutes had been violated.

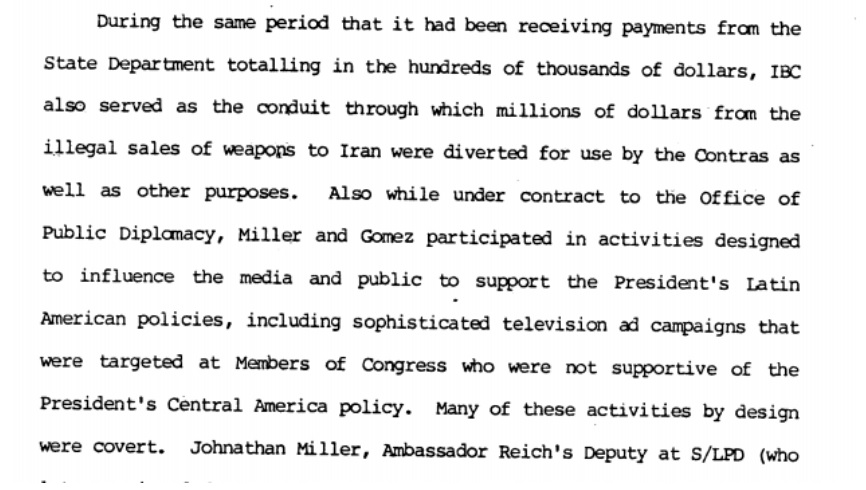

The lobbying statutes that had been violated were no small matter, yet they were all but covered up by denying access to information. As a result, they’ve all but been forgotten by history. The documents, however, survive. The Senate’s final staff report concluded that the State Department’s Office of Public Diplomacy for Latin America and the Caribbean (S/LPD) “played a central role in the creation and management of the private network involved in the Iran/Contra affair.” The report also concluded that the S/LPD had been created and managed “by operations in the National Security Council who maintained close ties with Oliver North and former CIA Director Casey.” As the Congressional Iran-Contra report would note, the NSC staff member responsible for overseeing the S/LPD was also a former CIA employee.

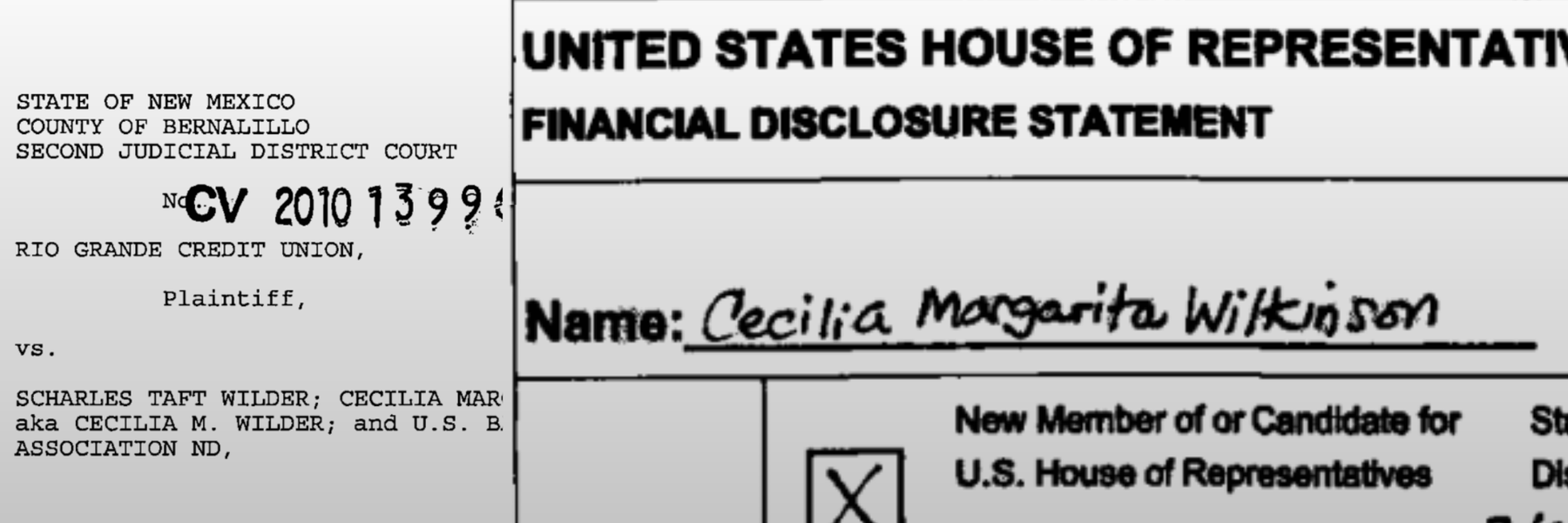

The S/LPD’s origins become especially significant in light of the S/LPD providing question no-bid contracts to International Business Communications (IBC). While being paid by the S/LPD, IBC not only served as the “conduit through which millions of dollars from the illegal sales of weapons to Iran were diverted for use by the Contras as well as other purposes” but as a source of propaganda. Gomez, one of IBC’s principals, participated in covert and illegal propaganda efforts “designed to influence the media and public support for the President’s Latin American policies.” Alarmingly, this included “sophisticated television ad campaigns that were targeted at Members of Congress” who disagreed with President Reagan.

Not even GAO’s conclusion that these efforts violated anti-lobbying statutes and the Senate’s conclusion that the office funding the efforts had been created by the NSC and reported to the former CIA Director was enough to convince Congress to give the GAO real access to CIA’s records. While the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee chairman would introduce legislation to allow the GAO to evaluate the Agency, the legislation, and the more limited proposal introduced in the House, quietly died when referred to the intelligence committees.

Instead, the Committee’s control was further concentrated in 1988, when their audit staff was created. Meant to be “a credible independent arm for Committee review of covert action programs and other specific Intelligence Community functions and issues,” it was meant to provide an alternative to the GAO for auditing the Intelligence Community. In effect, it created another significant bottleneck to oversight while making it further subject to politically motivated manipulation, such was when the Republicans unilaterally fired the entire audit staff in 2005.

That same year, the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Office of Legal Counsel issued an opinion that attempted to more fully exclude GAO from the Congressional oversight process. The GAO disagreed with the DOJ’s legal analysis, arguing that the exclusion was not as categorical as the DOJ said.

During the 106th Congress, which operated from January 3, 1999, to January 3, 2001, the audit staff was composed of three full-time auditors. These auditors were expected to lead or support “the Committee’s review of a number of administrative and operational issues relating to the agencies of the Intelligence Community.” In comparison, the GAO had 3,275 full time employees, many of whom had or could be granted security clearances. This importance of this imbalance is highlighted in a 1985 EYES ONLY memo written by the Agency’s Executive Director, stating that the Agency had “for the last 40 years held the GAO and their armies of auditors at bay.” It was certainly easier for the Agency to deal with Congress’ three full time auditors, subject to political control, than it was to deal with the “armies of auditors” at the independent GAO.

It doesn’t seem that the Senate’s audit staff expanded over time. When they suddenly replaced in 2005, the staff still consisted of only three members.

The Agency would rather brazenly refuse to allow the GAO to audit the Agency “with respect to funds authorized for the Nicaraguan Resistance.” Fresh on the heels of Iran-Contra, the Agency insisted that since any such funds would break the law, there was nothing for GAO to audit, and therefore GAO’s request was being denied. Similarly, any other hypothetical assistance to the Nicaraguan Resistance would have been subject to Congressional oversight, and on which grounds the Agency would similarly deny the GAO access.

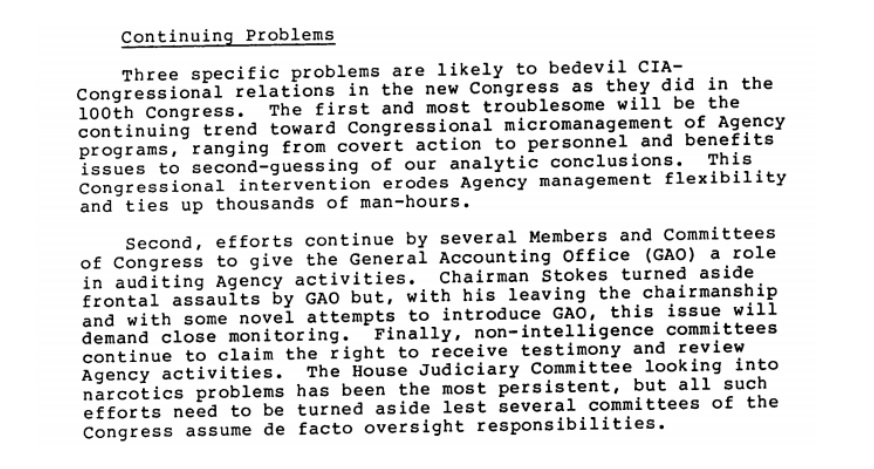

A 1988 memo makes it clear that the Agency’s interest wasn’t simply in limiting the GAO’s access, but in similarly preventing any committees other than the intelligence committees from claiming any degree of oversight jurisdiction. The CIA was leery of “Congressional micromanagement” of the Agency, arguing that “Congressional intervention erodes Agency management flexibility and ties up thousands of man-hours.” The Agency apparently felt rather strongly that personnel benefits was in the jurisdiction of the intelligence committees only. They were equally leery of the GAO and the House Judiciary Committee’s interest in the drug war. According to the Agency, “all such efforts need to be turned aside lest several committees assume de facto oversight responsibilities.”

That same year, Congressman Leon Panetta introduced legislation to assert GAO’s authority to audit the Agency. According to a CIA memo from their Office of Congressional Affairs, Panetta was convinced to drop the matter in favor of allowing the Congressional committee to focus on another bill which was introduced but was never passed. When he became Director of Central Intelligence in 2009, he does not appear to have taken the opportunity to significantly increase CIA’s cooperation with GAO.

However, the Agency wasn’t finished limiting GAO’s ability to conduct oversight. A few years later, CIA drew what it called a “hard line” against GAO’s oversight - a hard line that continues to this day.

Read the 1988 memo embedded below:

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons