Even for students of the history of the Intelligence Community (IC), Robert Blum is all but forgotten except as a bureaucrat, a professor, and the head of a philanthropic foundation with ties to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In reality, he was a counterintelligence chief who worked for several agencies, built large pieces of the United States’ foreign economic policies, had the Director of Central Intelligence fired, and redesigned a significant portion of the IC, including its mechanisms for covert action and propaganda.

The few sources that discuss him do so only briefly, and rely mostly either on a handful of recycled documents from the Foreign Relations of the United States, or on recycled innuendo and secondhand information. The Asia Foundation’s website entry on Blum not only omits a considerable amount of information, it contains factual inaccuracies. Even the CIA’s website contains some inaccurate information on Blum’s career. In contrast, this article (and its follow-up on the Asia Foundation) are based on a review of more than 200 primary source documents, almost all of them previously classified, totaling well over 1,000 pages of information.

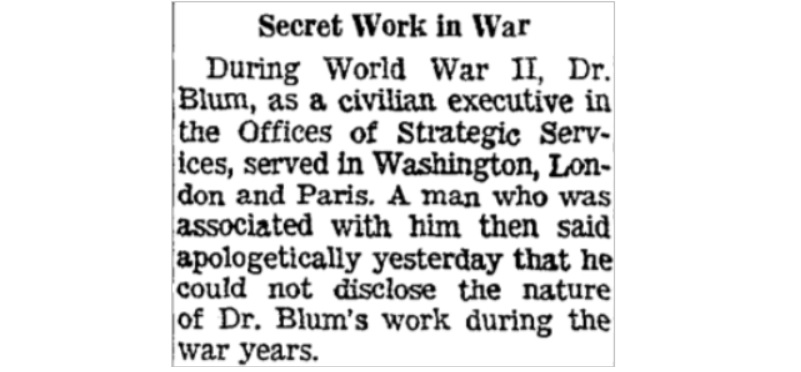

According to the available records, Blum began his career as an academic relatively quietly. At Yale University, he was a research assistant and an instructor for international relations until 1942. After the attack on Pearl Harbor led to the United States joining World War II, and the eventual creation of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in June 1942, Blum left his position at Yale to join the war effort. Specializing in counterintelligence, planning, and liaison, Blum spent much of his time during the war split between Washington D.C., London, and Paris. By late 1944, Blum had been made the Chief of the X-2 Branch in Paris, the OSS’ counterintelligence branch. By early 1946, Blum was helping direct all of the OSS’ counterintelligence operations as the Assistant Chief of the X-2 Branch. When his obituary was published, his work with the OSS remained largely classified. His OSS service was only briefly acknowledged in obituary, and no information was provided about the type of work he did.

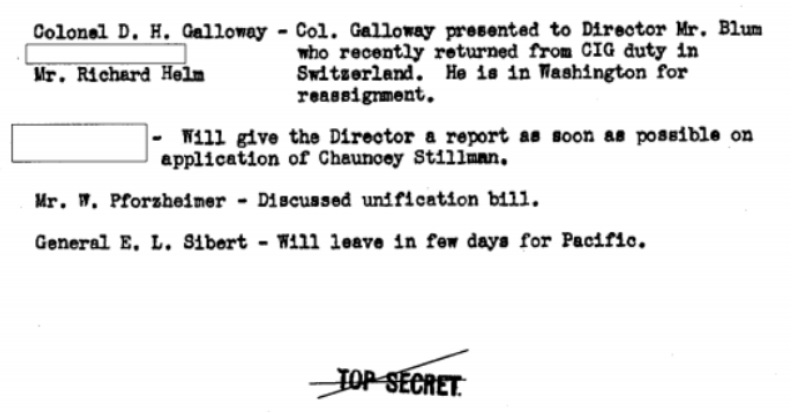

Blum’s service, however, didn’t end with the OSS, but continued with the organization’s transformation into the Strategic Services Unit and then the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), the direct predecessors to CIA. According to a previously TOP SECRET diary of former CIG Director (and later CIA Director) Roscoe Hillenkoetter, on July 11, 1947 the Director was introduced to Blum, who had “recently returned from CIG duty in Switzerland” and had returned to Washington for reassignment.

While the National Security Act of 1947 would be signed several weeks later, replacing the CIG with the Central Intelligence Agency and creating the National Security Council (NSC), it seems that Blum did not join the CIA. Instead, he became the assistant to Secretary of Defense James Forrestal for NSC and CIA affairs.

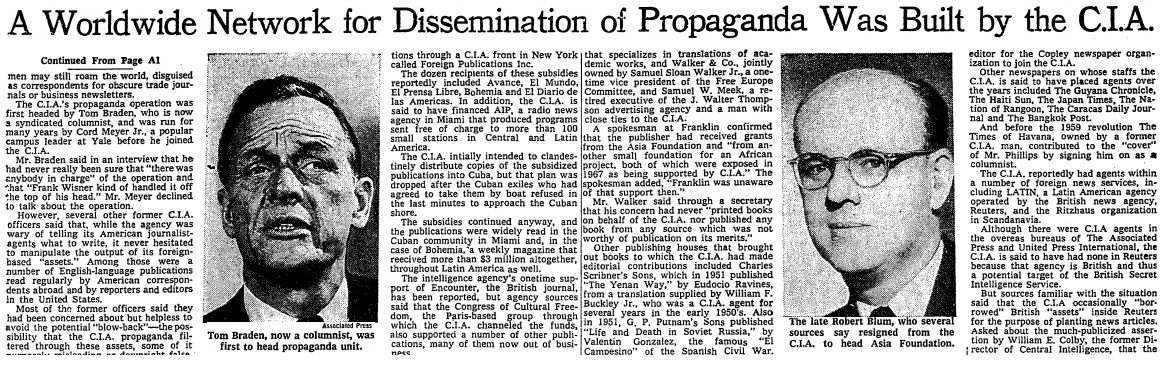

While in that position, and in subsequent posts, Blum would work very closely with the Agency. However, there’s no evidence that he worked directly for the Agency, despite reporting from the New York Times and later by other sources which would cite an out of print book written by Colonel Corson. Since Corson wasn’t a member of the Agency and documents do not appear to confirm an allegation attributed to his “bitter, cynical and smart alecky book,” the allegation isn’t being taken at face value, or as a reflection of the actual chain of command. Without knowing the identities of the New York Times’ sources, it’s impossible to determine whether they made a similar mistake in reporting that sources said Blum had left the Agency to run the Asia Foundation. However, as discussed further below, documents show that Blum was actually employed by the government at the same time that he was running the Asia Foundation.

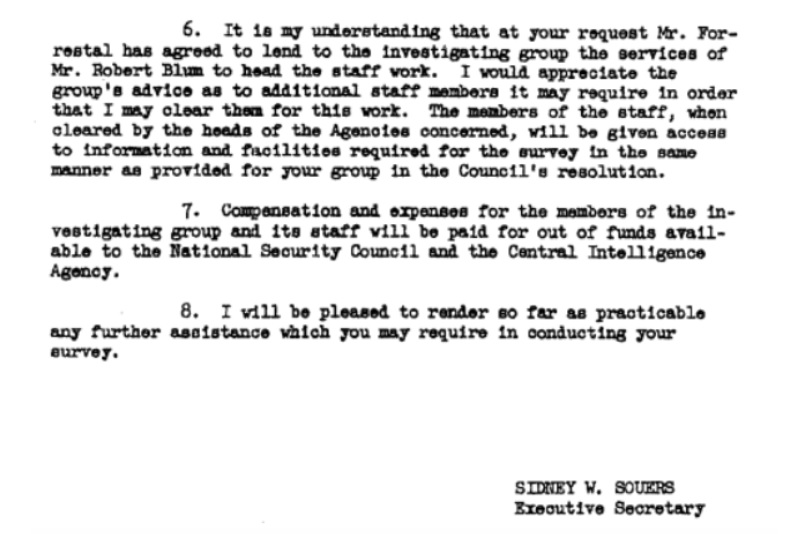

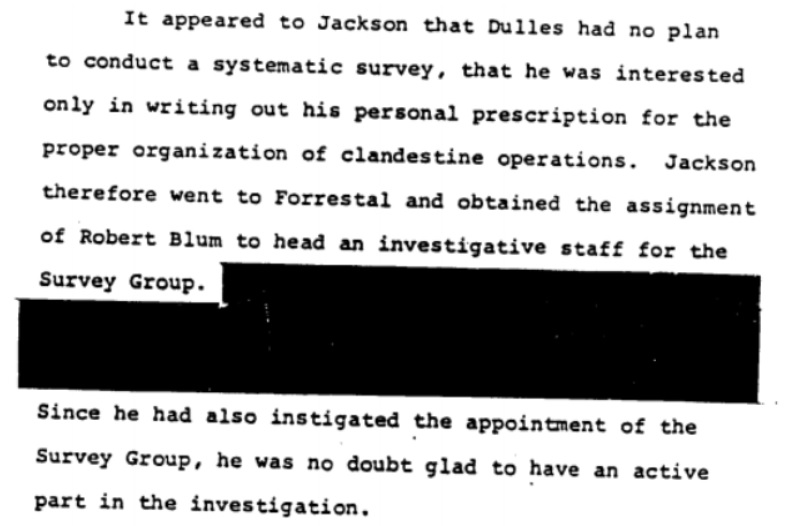

Outside of his presidency of the Asia Foundation, Blum’s best known (in CIA’s internal histories, at least) for his CIA-related work on the NSC Intelligence Survey Group, which produced the Dulles-Jackson-Correa Report (also known as Intelligence Survey Group (ISG) and the Dulles Report). During this time, Blum was “loaned” from Forrestal’s staff to the ISG, for which he headed the staff. It appears that, at this time, Blum was paid “‘out of funds available to the NSC and the Central Intelligence Agency.” Considering the circumstances of his employment, as well as the numerous pieces of correspondence Blum wrote on NSC letterhead, including ones to senior CIA personnel, it seems likely that Blum’s work fell more directly under the NSC’s purview than CIA’s.

However, Blum’s full role in the committee has been largely ignored by history outside of his handful of mentions in the Agency’s internal histories. Blum was not only in charge of the staff work, he was at least partially responsible for the creation of the working group in the first place.

As one internal history noted, Blum was no doubt pleased with this result. As noted below, he was similarly amused when he was later responsible for helping draft the response to the group’s work.

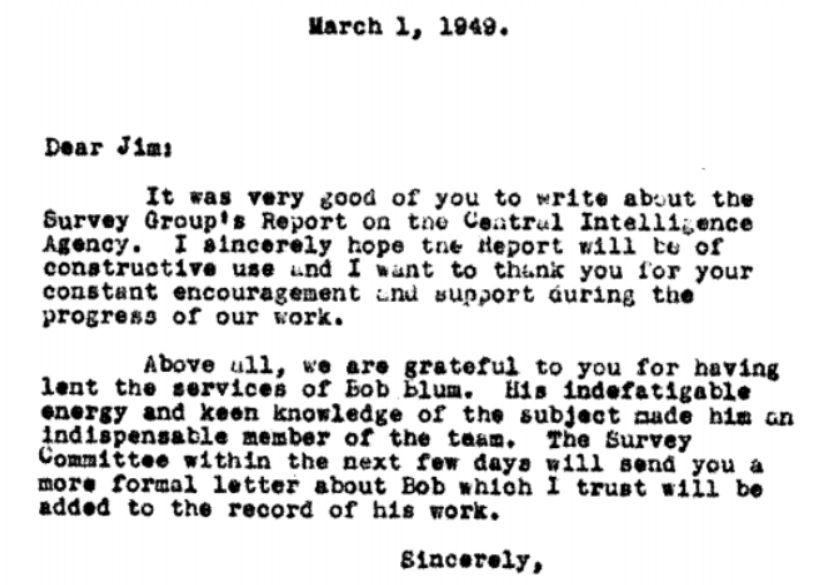

While it might be tempting to dismiss Blum’s work on the staff as merely administrative, this would contradict the repeated statements of Allen Dulles and others. One early note, unsigned but almost certainly written by Dulles, was quick to praise Blum’s “indefatigable energy and keen knowledge of the subject.”

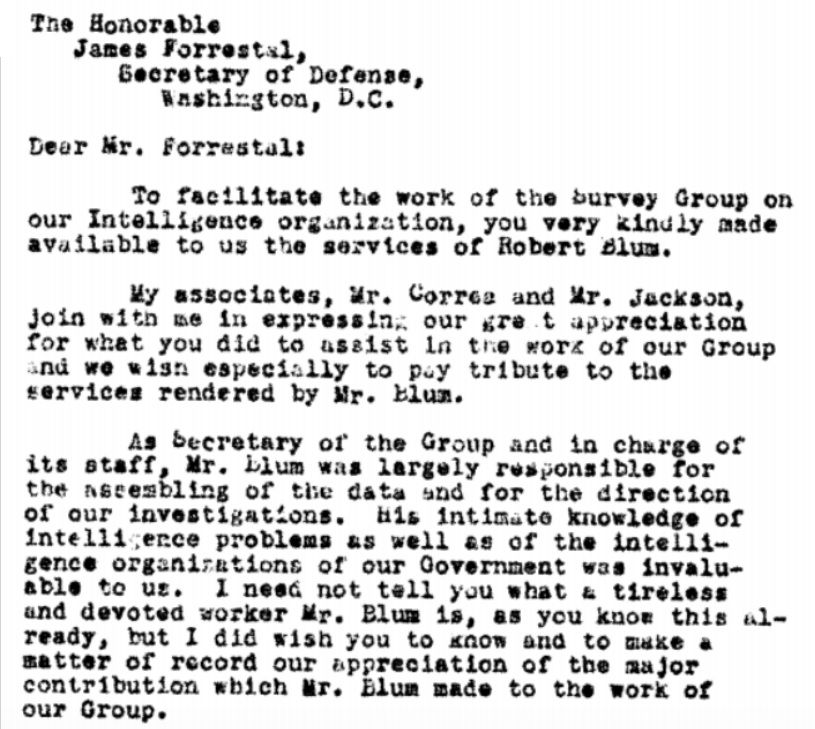

A follow-up letter, dated the next day, praises Blum in more detail and credits him with being “largely responsible for the assembling of the data and for the direction of our investigations.”

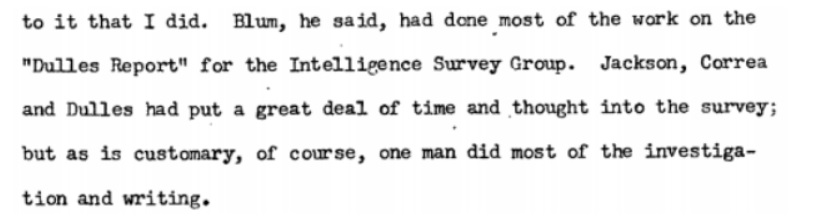

In a previously TOP SECRET interview with Allen Dulles for the history of General Walter Smith’s tenure running the Agency, Dulles is even more candid. While Dulles, Jackson and Correa had all “put a great deal of time and thought into the survey,” it was Blum who “had done most of the work.” This apparently included doing “most of the investigation and writing.”

Blum’s responsibility for writing most of the report was also confirmed by Admiral Sidney Souers in a formerly TOP SECRET interview, while another document seems to show that Blum wrote the tentative outline for the final report.

One declassified history clarifies that Blum drafted the entire body of the report, with only the summary having been written by Jackson.

Blum’s work with the report didn’t end when it was issued. Blum was the executive secretary to McNarney while he worked on NSC 50, informally known as the McNarney Report. NSC 50 was, essentially, the comments and recommendations following up from the Dulles Report. As Admiral Souers noted, Blum was amused by the fact that he was essentially making recommendations on his own findings.

Blum’s work on the report was not entirely uncontroversial. While many of the findings and recommendations were ultimately accepted, the recommendation that DCI Hillenkoetter (among others) be replaced was met with considerable debate and resistance. It did, however, lay some of the the groundwork for Hillenkoetter’s later dismissal over the failure to produce any warning of North Korea’s invasion of South Korea, after which he was replaced by as DCI by General Smith.

Even amid the resistance to the possibility that Hillenkoetter be replaced, the effect of the report and the blame it placed on CIA’s leadership was “devastating,” according to one of CIA’s declassified histories.

According to one of the declassified interviews with Admiral Souers, the report’s recommendation that Hillenkoetter be replaced as DCI wasn’t accidental. Souers’ alleged that Blum had been determined “to get Hillenkoetter fired” and that this was the source of the Committee’s focus on CIA.

Hillenkoetter similarly blamed Blum for his being let go, apparently stating that everyone had been “mislead by a clever clerk, Robert Blum.”

The only work to discuss Blum’s involvement in this period in-depth is The Central Intelligence Agency - An Instrument of Government (through 1950), a formerly SECRET internal CIA History. According to the Agency’s History Staff, the report had a “definite and sometimes controversial point of view, heavily criticizing the Dulles Report. Reportedly, when Dulles later became head of the Agency he had access to the report further restricted.

The Dulles Report’s impact wasn’t limited to laying the groundwork for Hillenkoetter’s dismissal. It resulted in significant change to the way the Agency did business, replacing the Office of Reports and Estimates with three new offices: the Office of National Estimates, the Office of Research and Reports, and the Office of Current Intelligence. Parallel to those changes, Blum’s work with the NSC laid the groundwork for the creation of Office of Special Projects, quickly renamed the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC) and responsible for covert psychological operations and paramilitary action. Blum’s involvement wasn’t limited to the planning of NSC 10/2, which created the Office of Special Projects, he was involved in the implementation of NSC 10/2, as well.

When it was initially created, the OPC was a deliberately independent organization that reported through the State Department and coordinated with various parts of the Intelligence Community. This, however, was not to last. The Dulles Report, which was being prepared at the same time as the groundwork for the OPC, was issued several months later. The report not only recommended keeping the OPC within the Agency, it recommended combining it with the Office of Special Operations. Several years later, during period when DCI Smith was implementing reforms following on the Dulles Report, the OPC was combined with the Office of Special Operations to form the Directorate of Plans.

Considering these changes alone, the Congressional Research Service’s statement that the report’s “recommendations would become the blueprint for the future organization and operation of the present-day CIA” is hardly hyperbole. The report, which was largely directed, managed and written by Blum, served as the basis for a number of IC changes and reorganizations which were implemented and refined over the course of several years.

Read Part 2 here.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons and licensed under Creative Commons BY 2.0.