Read Part 1 here

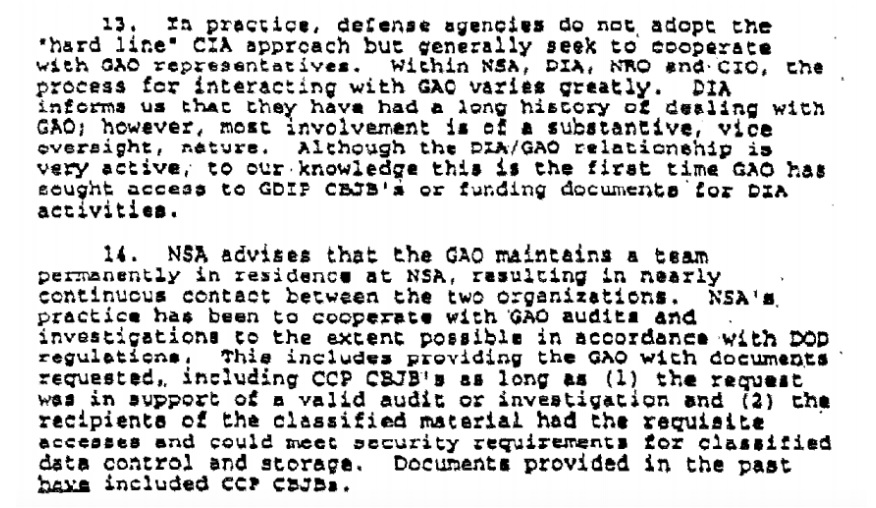

Other agencies didn’t share CIA’s “hard line” approach to oversight. While there was a great deal of variation in the procedures of how they cooperated with GAO, as well as the depth of that cooperation, most in the Intelligence Community generally tried to work with the GAO rather than categorically deny them access. The National Security Agency’s cooperation with the GAO was especially notable - a GAO team had taken up full time residency at NSA “resulting in nearly continuous contact between the two organizations.”

In the final weeks of 1993, the DCI was informed that the GAO was requesting access to materials which for DOD programs which were part of the National Foreign Intelligence Program (now the National Intelligence Program) and thus DCI controlled. The GAO had neither requested the DCI’s permission or even notified the DCI about this. After CIA’s Director of Congressional Affairs encouraged him to, the Executive Director for Intelligence Community Affairs informed the GAO that they “could not agree to such access,” something which they now asked the DCI to formally affirm.

There were limits to the recommended policies set out in the memo, however. While the DCI could use their authority to withhold access to documents that related to collection requirements and the correlating information in the Congressional Budget Justification Book (CBJB), but not to the operational details of each mission. CIA’s Director of Congressional Affairs warned that attempting to do so would inevitably create a conflict with the intelligence committees and with the Secretary of Defense.

Avoiding a conflict with the Congressional committees was a priority, and the memo recommended assuring them that “the policies do not sanction the denial of information to Congressional Committees.” When a Congressional Committee later held a hearing on CIA’s refusal to cooperate with oversight, and to explicitly discuss this memo, CIA refused to produce anyone to testify and answer the committee’s questions. The memo was also not meant to “dramatically change” how agencies dealt with the GAO, with one “major exception” in the NSA’s practice of sharing CBJBs.

There were risks, however - the intelligence committees might decide to bring the GAO into the process. The Congressional committees had limited resources, especially compared to the GAO, and might be sensitive to the complaints of Congress’ investigative arm. The memo emphasized that the Agency response should be that this contradicted the Agency’s legal mandate.

Notably throughout the memo, little to no mention seems to be made of security necessitating GAO be denied access. The argument seems to have been that the Agency legally could deny GAO access, and therefore should. To CIA, it was a foregone conclusion that it was desirable to undercut GAO oversight.

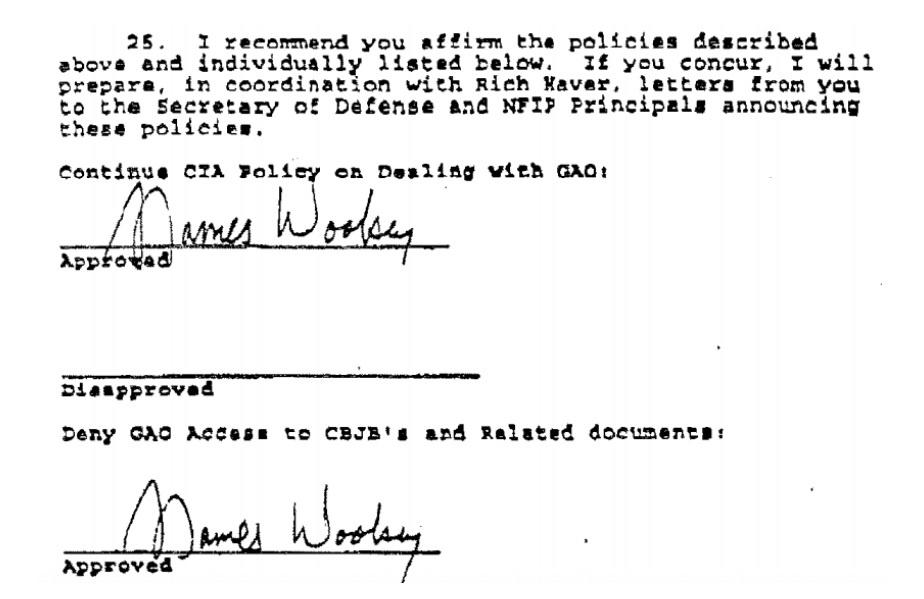

CIA Director James Woolsey signed off on the recommendations, affirming and codifying the Agency’s position that they would not share information with the GAO.

The “hard line” that the Agency drew against GAO oversight in this memo would form the basis for their refusal to cooperate for years to come. When the House Committee on Government Reform held a hearing in 2001 to determine if CIA’s refusal to cooperate with Congressional inquiries was a threat to effective oversight, one of the things they were looking at was this memo. During the hearing, Congressman Gilman (R-NY) criticized the memo as a “dated, distorted concept of oversight.” It was this concept, the Congressman argued, that led to the Agency’s refusal “to discuss its approaches to government-wide management reforms and fiscal accountability practices.”

While the Agency had insisted that the memo’s policies to limit GAO access would not be used to limit Congressional access, that is precisely what happened. It would be easy to think that once the memo had put the precedent in place, the attitude permeated the Agency. That attitude had been there from the beginning, as CIA’s efforts to cooperate with the GAO audits in the early 1960s were obviously sabotaged. One of the Agency’s Inspectors General had gone so far as to say that CIA should choose when it’s subject to oversight. The 1994 memo did little to change the Agency’s attitudes or actions - it was merely the codification of their long escalating policy to deny the GAO access to information. This effort continued into the new millennium, as will be explored in a future article.

You can read the 1994 CIA memo below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via CIA’s Flickr