As hordes of white men with dopey haircuts take to the streets to denouce progress, it’s worth taking a look at a moment in American history when a bunch of rich dudes attempted to turn the country in a fascist dictatorship through overt violence, before they realized they could just hijack the electoral system.

In 1934, General Smedley Darlington Butler reported to the FBI that he’d been approached by leaders of the American Legion to lead 500,000 men into battle against Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s government and install a dictator. The effort allegedly had both the blessing and funding of a number of big businesses in the United States, including J.P. Morgan and Dupont, and is often referred to as “The Business Plot,” or “The Wall Street Putsch.”

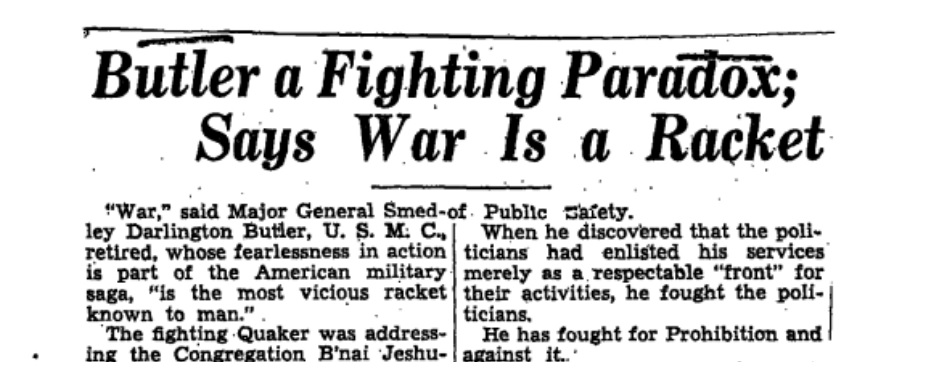

Although Butler was a hero of multiple American wars at the time the most decorated Marine in U.S. history, perhaps the alleged conspirators thought it was safe to approach him because he’d since declared that war was a “racket.”

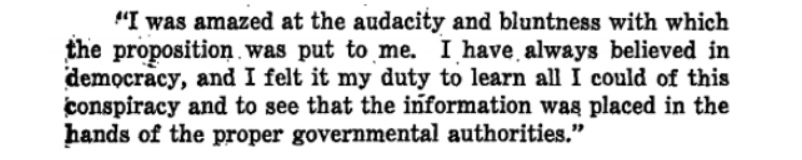

Butler claimed that he pretended to go along with the plan because he felt it was his duty to gather as much information for law enforcement as he could:

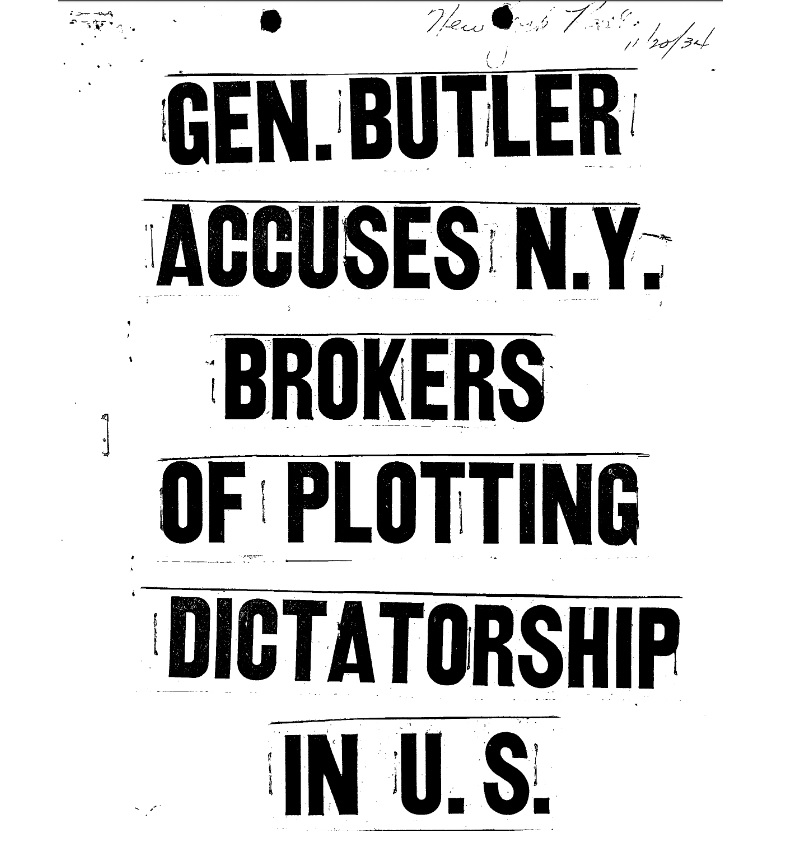

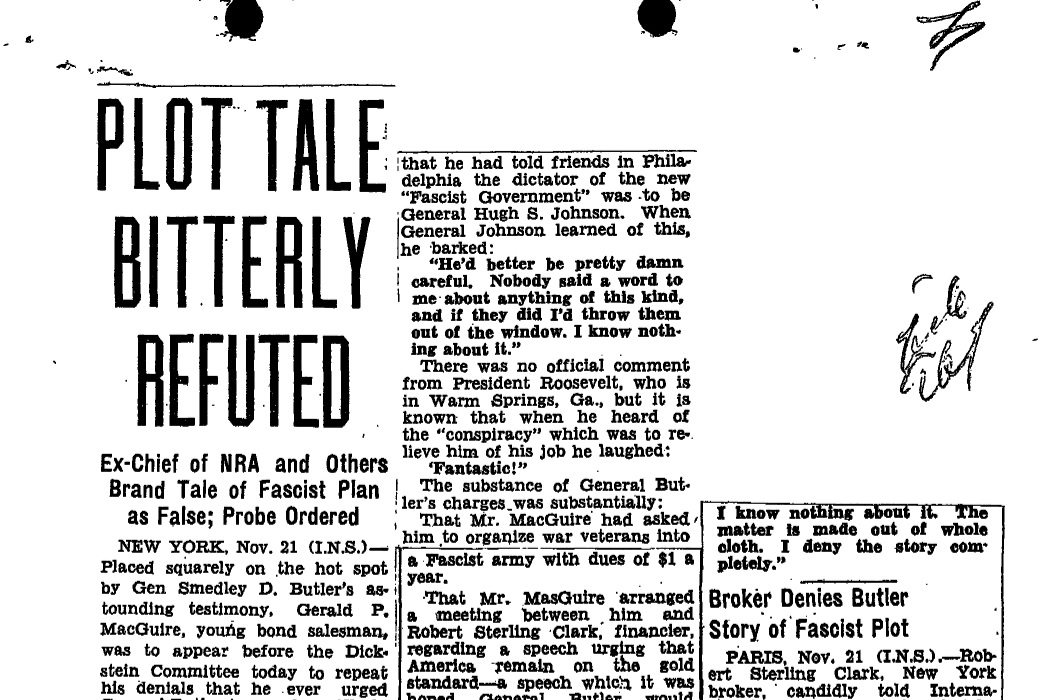

The press was all over the story, and Butler’s file contains numerous news clippings about the affair. According to one report, the man who approached Butler, Gerald C. MacGuire vehemently denied having any part in the plot:

MacGuire was a World War I veteran, Wall Street bond salesman, and former commander of the American Legion’s Connecticut branch. Grayson Meller Provost Murphy, who was MacGuire’s employer and had connections to numerous businesses, was also named by Butler as a conspirator.

MacGuire admitted to having met with Butler, but denied there was any sort of plot in an interview with the New York Post, telling the newspaper that he’d told Butler “General, you’re a damn fool to fall for all those outfits. You’ll be the one holding the bag. Vigilantes of the west and so on. None of them fascists, just crack pots.”

In another newspaper interview, MacGuire was described as “plaintive,” claiming he was blindsided by the accusations from a man said he thought was his friend:

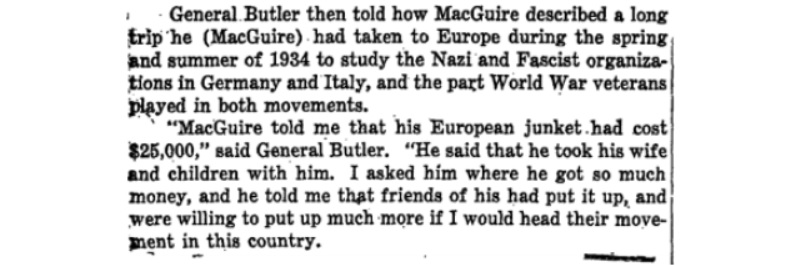

Another news clipping said the financial backers of the plot had sent MacGuire on a seven month trip to Europe to research how veterans groups over there had played a role in mobilizing a fascist political movement, in hopes of replicating their success in the United States:

Upon hearing about the conspiracy, Roosevelt reacted with the dismissive mirth of a man who didn’t take the threat seriously:

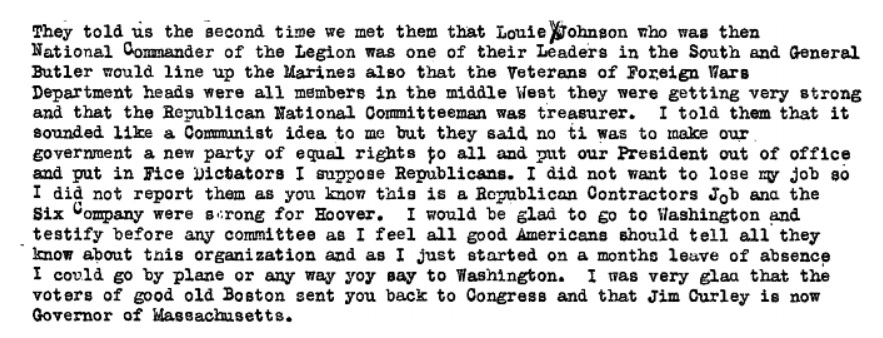

That same year, Peter A. Green of Six Companies Inc., which according to its letterhead were the “builders of the Hoover Dam,” wrote to House Un-American Activities Committee member John W. McCormack, who was investigating the plan along with Samuel Dickstein as part of the McCormack-Dickstein sub-committee to tell him that in March 1933 he’d been approached by two men claiming to be part of an organization called the American Fascist Veterans Association.

Green was the Vice Commander of the Boulder City American Legion Post, and he said the men inquired as to whether he’d be interested in leading the western wing of their fascist enterprise.

Green says in his letter that he was told that Butler was already on board with the plot, in addition to the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). Green mostly seemed concerned with trying to worm his way out of being seen as complicit for not reporting the incident sooner:

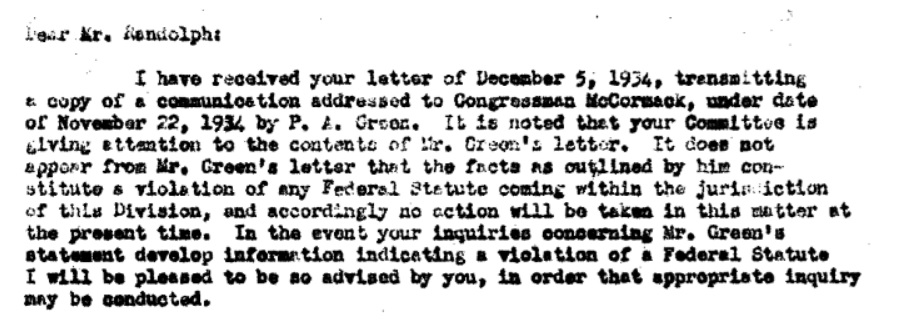

McCormack contacted then FBI Director J.Edgar Hoover about the matter. McCormack received a response from Hoover just a few months later, saying that as far as he could tell by the facts put forth in Green’s letter, no federal laws had been broken, and he didn’t see the need to take any action:

Oddly enough, an FOIA request for files on MacGuire turned up a “no responsive documents,” even though, the file the FBI released on Butler made numerous references to MacGuire.

The wealthy folks who had committed to funding the plot left MacGuire “holding the bag” just as he claimed to have warned Butler they’d do to him. Just one month after the McCormack-Dickstein Committee released its final report, MacGuire died of natural causes at the age of 37.

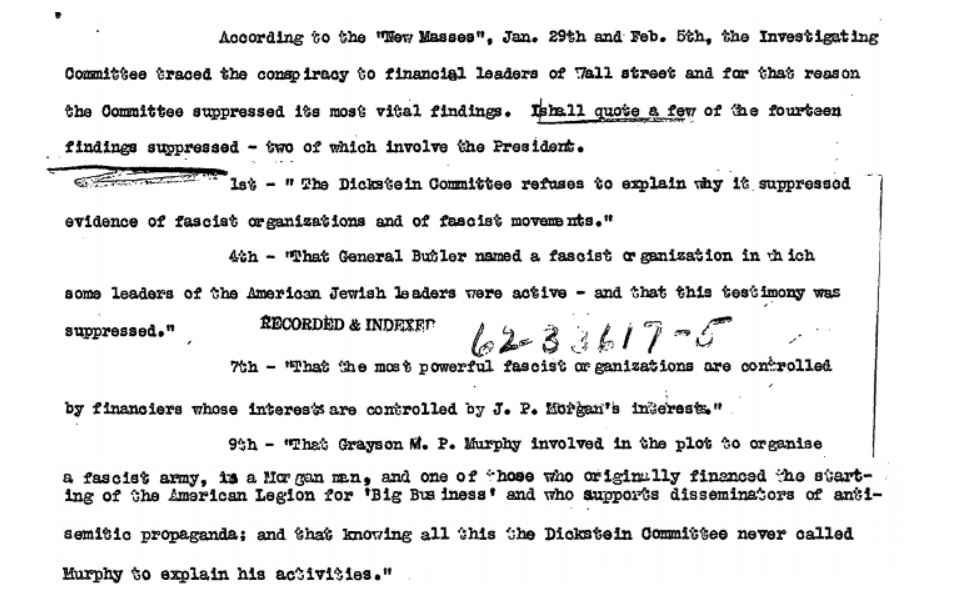

Even after the investigation ended and most people had moved on, some people were unsettled by the fact that nobody was held accountable for the plot, and there were accusations that the McCormack-Dickstein Committee had been less than rigorous in its investigation.

According to a letter dated March 18, 1935, and addressed to President Roosevelt, E.C. Rodwick of Santa Barbara California suggested that the McCormack-Dickstein Committee suppressed evidence that pointed to “financial leaders of Wall Street” having supported the alleged attempt at a fascist coup:

As for Butler, he went on with his life, and the incident doesn’t seem to have dulled his affection for the Bureau. In the late `1940s, Hoover and his agents exchanged letters with Butler, thanking him for the lovely things he said about the Bureau at various speaking engagements …

and in letter to Hoover from 1938, Butler responded that he was more than happy to promote the FBI.

In 1961, Hoover received a newspaper clipping from someone whose name has been redacted, which quotes Butler as a young Marine saying that he was a “high class muscle man for big business and Wall Street.”

Hoover didn’t seem interested …

likely due to the small fact that by that time, Butler had been dead for two decades. Read the first part of Butler’s file embedded below, and the rest on the request page.

Image by USMC Archives via Flickr