A new FOIA release shows the FBI Director’s Office responded to FOIA requests for known files on deceased FBI officials by presenting options that seemingly included a law enforcement investigation/proceeding against the requesters, with one email calling the requests “SUSPICIOUS.” While the emails are heavily redacted to conceal the identities of the FBI officials involved in the discussions, the Bureau repeatedly left personal information of the different FOIA requesters unredacted, despite having clear guidelines and no privacy waivers.

The FBI’s Dead List, which compiles a list of FBI files on subjects the Bureau knows to be dead, can be a wonderful resource for FOIA requesters. The list confirms the existence of specific FBI files as well as the subject’s death, removing the need to provide separate proof of death in order to avoid unnecessary redactions. The FBI has recently begun claiming that they can’t locate the updated copy of the file, a claim that the Department of Justice has upheld on appeal. The most recently released copy of the Dead List identified approximately 7,000 deceased FBI officials on whom the Bureau maintained files. Due to the obvious public interest in these files, they were requested.

To accomplish this, the names of the subjects were extracted from the Dead List and a simple script written to submit FOIA requests for them. The requests were submitted on February 29th 2016, with the script and data made available online so that others could make their own requests and trigger the DOJ’s “rule of three” for frequently requested records, which would see the files posted online by the FBI. The FBI acknowledged a large number of them before they began ignoring them. Over a month later (after the Bureau had exceeded legal time limit), the FBI sent a letter stating that they had “received an exceedingly high volume of submissions” which they would not accept.

According to the Bureau, fulfilling the FOIA requests would have prevented the FBI from fulfilling FOIA requests. Their letter stated that the “manner of submission interfered with the FBI’s ability to perform its FOIA and PA statutory responsibilities as an agency. Accordingly, the FBI did not accept these submissions on February 29th, 2016.”

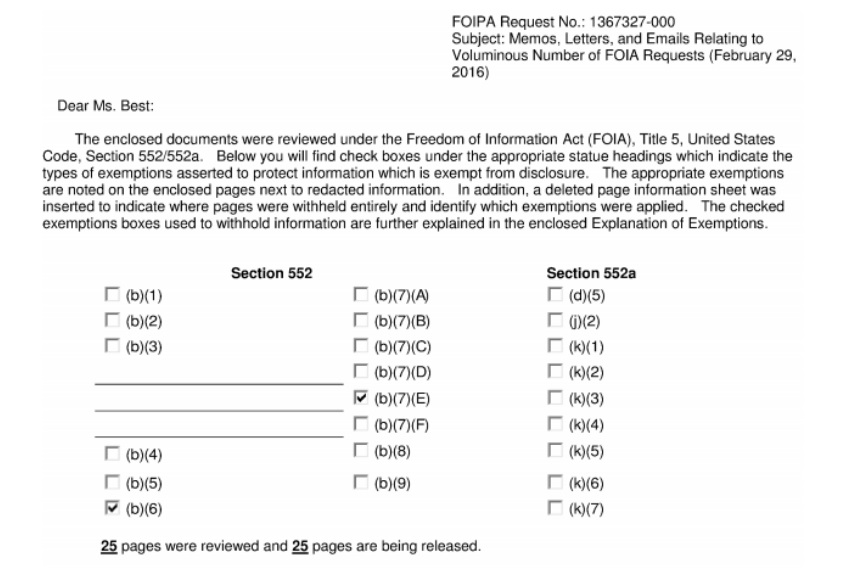

In response, a new FOIA request was filed for:

All internal memos, letters and emails relating to a voluminous number of FOIA requests that were submitted on February 29th, 2016 and all discussions of how to handle said requests. I also hereby request all email maintenance complaints, logs and other documentation of problems associated with the FBI email system for February and March 2016.

After ten months (again well outside the legal limit), the Bureau finally responded with 25 pages of heavily redacted emails. The FBI provided no records indicating any problems with their email system for February or March, and withheld no pages in their entirety. Since the FBI’s FOIA office is always thorough in their searches and acts in good faith for David Hardy, the FBI’s relevant Section Chief, is an honorable man, it might be safe to assume that these records do not exist. If they did, the Bureau would surely release them, if only to substantiate Hardy’s claim that the submission method caused interference for the FBI. Since the author’s free Gmail account was able to handle the number of emails involved, it’s hardly surprising that the Bureau’s system would be as well.

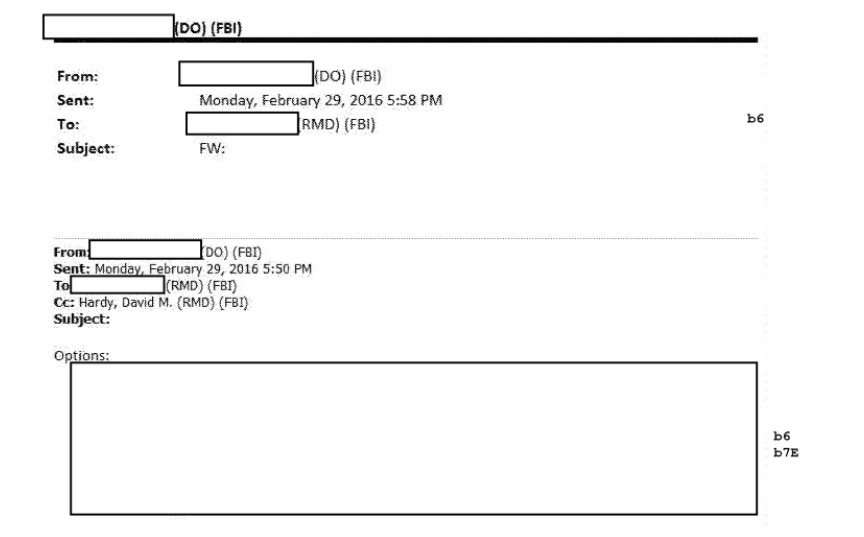

Perhaps the most revealing thing from the emails is that at least one person from the FBI Director’s Office became involved, as indicated by the DO abbreviation. Though the text of their email is redacted except for a single word, if one believes the b(7)e exemption cited by the Bureau, they discussed “techniques and procedures for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions.” There would be no reason to discuss those techniques or procedures in this instance if the Bureau wasn’t considering applying them in response to the FOIA requests.

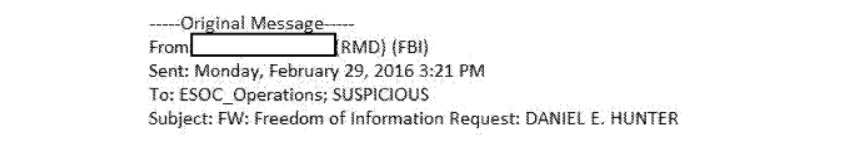

Another email shows that the Bureau apparently considered the FOIA requests “SUSPICIOUS.”

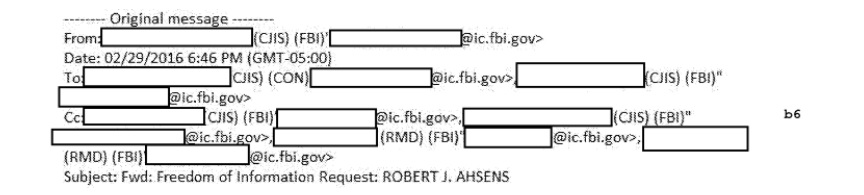

Other emails show that the FBI’s FOIA office consulted a number of people from the Criminal Justice Information Services division. Among other things, CJIS is responsible for the Bureau’s National Crime Information Center, Uniform Crime Reporting, Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System, and the National Incident-Based Reporting System systems.

Despite redacting the names and email addresses of the public servants handling the case, the FBI released not only the author’s name and address in the file (technically improper since there was no waiver, albeit understandable) but the name, email address and home address of another requester who also used the script to file requests. Their name along with their email and physical addresses were left unredacted not once, not twice, not thrice - but seven times, not including the email headers, several of which also showed their name and email address.

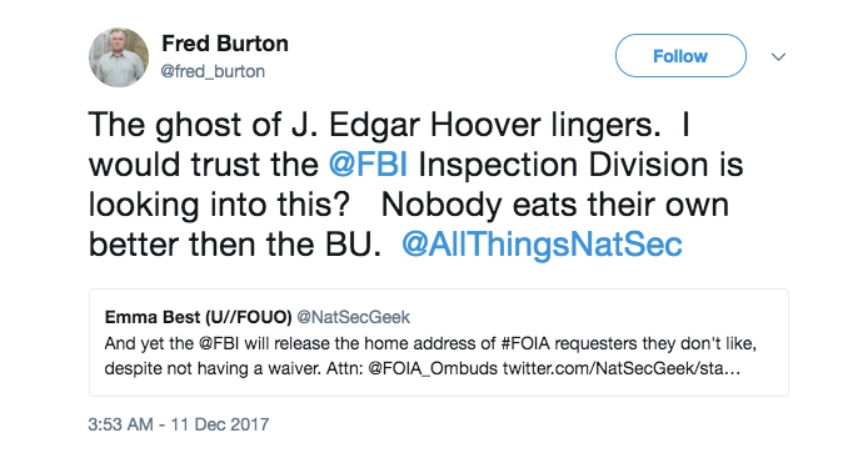

It’s hard to imagine that the Bureau, which once hung a sign in their FOIA office instructing people that “when in doubt - cross it out” would fail to redact this information so many times by accident. In context, it’s hard to see it as anything but retaliatory. As Fred Burton (Stratfor’s Vice President of Intelligence) put it, not only is it the sort of pettiness one would expect from the lingering ghost of J. Edgar Hoover - it’s the sort of thing that should be investigated.

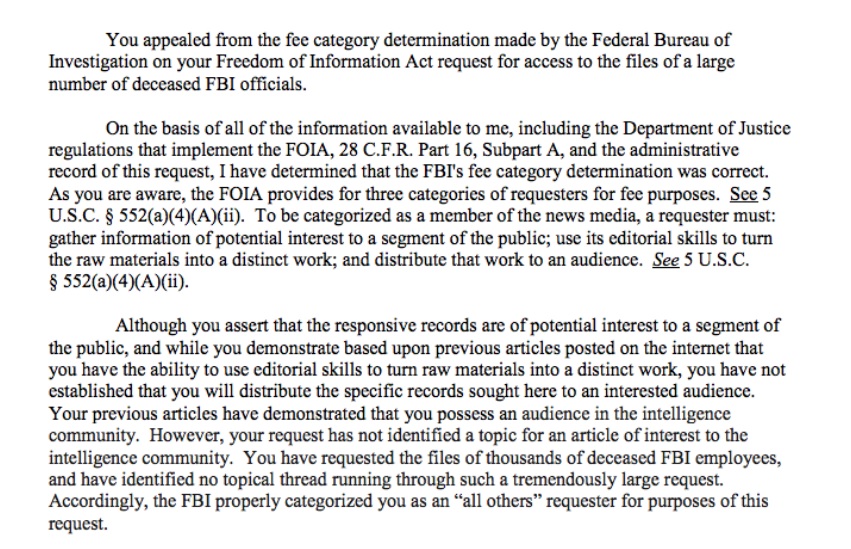

After the FBI threw away the separately filed FOIA requests en masse, including the ones that released emails show they had already processed into their FOIPA system, a separate, single request was filed for the files of deceased FBI Officials which the Bureau had identified in the Dead List. In response, the Bureau identified several preprocessed files that it requested duplication fees for in contrast to their typical policy of providing preprocessed materials without duplication or review fees. The Bureau also denied the author the proper fee category. The FBI insisted, among other things, that there had been no demonstration that the author was a journalist, or that a distinct work could be distributed to an audience, despite the original FOIA request citing previous articles that had individually reached over 100,000 readers.

This was appealed to the Department of Justice, which not only upheld the Bureau’s decision but cited logic that is faulty and contradicted by both the law. The DOJ’s arguments included stating that there was no “topic for an article of interest to the intelligence community” - despite the FBI being part of the that community. The DOJ also argued, in a single sentence, that there was no “topical thread” connecting the subjects of the request and that they were all deceased FBI employees. The FBI’s internal emails also contradicted their contention that there was no public interest, as the FBI was fully aware that there were already articles about the requests themselves - a fact which obliviates the Bureau’s contention that there would be no public interest in the results of those requests.

Therefore, the DOJ stated that “the FBI properly categorized you as an “all others” requester for purposes of this request.” [emphasis added] Even according to the DOJ’s own website, this contradicts the law. A second appeal was filed, pointing out that, among other things, “the news-media waiver … focuses on the nature of the requester, not its request.” The courts have also held that if a requester satisfies the news media “criteria as a general matter, it does not matter whether any of the individual FOIA requests does so.”

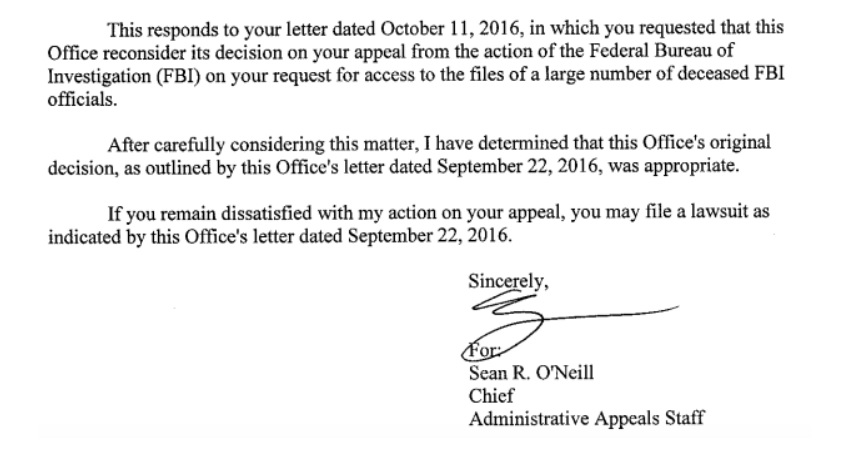

Nevertheless, the DOJ upheld their original decision.

It seems that when it comes to FOIA requests for FBI files on their deceased officials, the law is used to consider investigations or prosecutions against the requesters and to protect the privacy of the Bureau’s personnel, but not the privacy of the requesters or to fulfill the statutory FOIA requirements – which the FBI incredulously claimed they would be unable to fulfill if they had fulfilled the FOIA requests.

The emails - with personal information redacted by the author - are embedded below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Holloman Air Force Base