Sexual assault forensic examiners, commonly nurses known as sexual assault nurse examiners are specially trained to perform post-assault exams and carefully gather evidence from a victim’s body. Unfortunately, they are not found in every hospital across the country.

After hearing stories of women having to travel long distances to receive the exam that’s guaranteed to them under the Violence Against Women Act, so we began to file the same request with the health department in all 50 states asking for locations where a SAFE is available on staff or on-call. Like most of the other data surrounding sexual assault policies, what we’ve found so far varies widely, and there are large deserts – areas without easy access to a medical examiner.

Of the 50 requests we filed, only two states, Massachusetts and New York, gave us the information we were seeking. This data is not required to be compiled, so few state governments actually maintain up to date information, if any information at all, on which health care facilities offer sexual assault exams for children and adults.

The only official information about the availability of SAFEs comes from a 2016 Government Accountability Office report outlining how limited access and knowledge are.

“Data on the number of examiners nationwide are not available. In six states we contacted, officials told us rural areas particularly had unmet need for examiners,” said Katherine Iritani, a director of health care studies at the GAO who oversaw the report. “in rural Colorado, officials said that victims may need to travel for more than an hour to reach a facility with examiners.”

As a result, we began to contact victim services, sending emails to sexual assault response coalitions across the country. Many have gotten back to us with their own personal lists.

In Pennsylvania, for example, we were referred to the International Association of Forensic Nurses but, as their own website notes, the listing is unofficial and relies on institutions and individuals adding their own program to the database. They refer victims to the Rape, Incest, and Abuse National Network’s hotline for assistance.

We were also pointed in the direction of the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape. Our final list of Pennsylvania SANE programs comes from an excel sheet created in 2016 by Barbara Sheaffer, Medical Advocacy Coordinator of the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape.

Similarly, after the Alabama Department of Public Health had no records pertaining to our request, we were able to locate a list of sites after emailing Crisis Center Birmingham.

“Unfortunately, there is limited access for much of our state, more so for pediatric clients than adults, but all ages are underserved,” said Chris Jolliffee, the SANE Program Coordinator at Children’s Hospital of Alabama and a member of the Alabama Chapter of IAFN, in an email attached with a list of Alabama SANE sites he compiled in 2013.

Aside from a lack of centralized information creating difficulty for a victim trying to receive services, these unofficial lists are not reliably being updated. Programs also change rapidly, making it all the more important for victims to know where they can receive the important health services they are legally obliged to. In Pennsylvania, Sheaffer gave an example of one of the longest running hospital programs closing suddenly after the facility changed directors.

“Officials we interviewed said that maintaining a supply of trained examiners is challenging for multiple reasons, including limited training opportunities, technical assistance and other supportive resources, stakeholder support for examiners, and the physically and emotionally demanding nature of examiner work resulting in turnover,” said Iritani.

The hospitals and medical centers that do have examiners usually employ them on-call, sometimes for as long as 24-hours, and turnover is high.

“What we hear from SANEs is that it’s rewarding, but tough,” said Rebecca O’Connor, Vice President of Public Policy at RAINN. “The job demands availability, often at odd hours, and the ability to spend hours with victims of sexual violence at one of the darkest moments in their life. Combined, in many instances, with low pay and the impact of secondary trauma, it can be an extremely difficult job. “

Iritani said that many examiners work additional full-time jobs. They are often dissatisfied with their compensation and the program often lacks support.

“We heard anecdotally that some hospitals may be reluctant to support examiners and examiner programs due to the low number of sexual assault cases treated each year,” said Iritani. “Consequently, medical professionals may have to cover the cost of their examiner training courses themselves, and face lost wages associated with attending training. Hospitals may also be reluctant to send nurses to examiner training as it takes away from their regular shift availability,” she said.

The frequent closing of facilities and lack of full-time examiners and funds to train and maintain these programs means it wouldn’t be uncommon for a victim to have to wait for the on-call examiner to arrive at the hospital. According to the GAO report, officials in all of the six states examined

“told GAO that the number of examiners available in their state did not meet the need for exams, especially in rural areas. For example, officials in Wisconsin explained that nearly half of all counties in the state do not have any examiners available. In health care facilities where examiners are available, they are typically available in hospitals on an on-call basis, though the number available varies by facility and may not provide enough capacity to offer examiner coverage 24 hours, 7 days a week.”

These issues aren’t represented proportionally across the country.

“There is little question that some of the areas struggling the most with ensuring access to SANEs are rural communities,” said O’Connor. The GAO reported that “of the five rural counties in Central Colorado, only one county had an examiner available, and Nebraska officials “explained that it could take a victim 30 minutes or less in urban areas to up to 2 hours in rural areas to reach a facility that has an examiner available.”

The training of examiners also varies, as there is no federal training program and little governmental oversight.

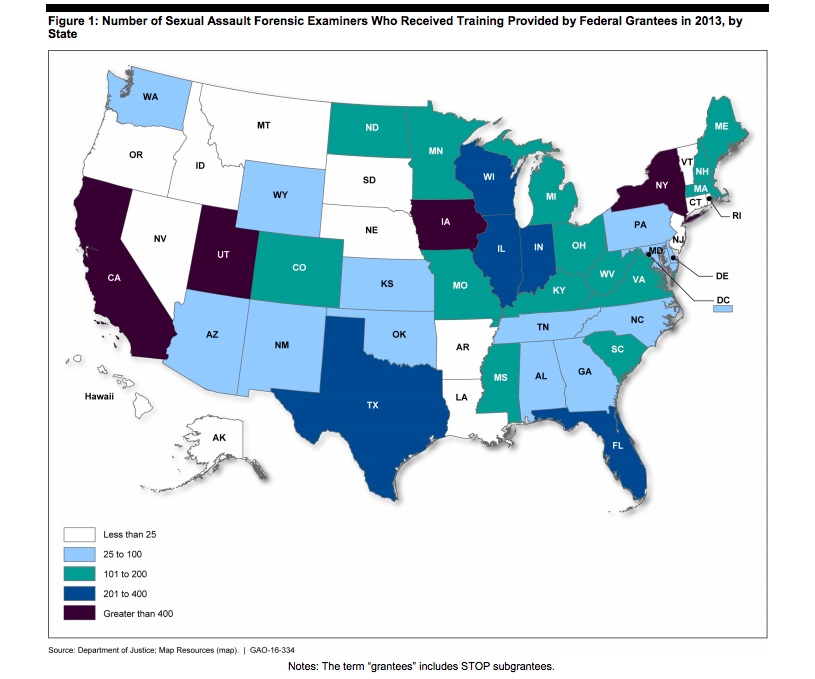

“We did report on the use of federal grant funds for training, and that certainly varied,” said Iritani. “In nearly all states in 2013, at least one federal grantee reported using grant funds to provide training for sexual assault forensic examiners in 2013. From the data, we couldn’t tell how many examiners received comprehensive training … Our report shows the variation among states in the number of examinees who received training provided by federal grantees - from less than 25 in a handful of states, to more than 400 in another handful of states.”

Read the full GAO report embedded below.

Image via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0