Decades after the fact, both the Central Intelligence Agency and Federal Bureau of Investigation remain highly secretive about parts of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International money laundering and embezzling investigation and the story of Khalid bin Mahfouz. While the FBI released some documents on bin Mahfouz and BCCI, with portions remaining redacted under citations of a pending law enforcement proceedings, the CIA flatly refuses to confirm or deny any information on bin Mahfouz, despite a former CIA Director having publicly (and falsely) accused him of being Osama bin Laden’s brother-in-law.

Following the Agency’s initial Glomar response to the FOIA request for records on bin Mahfouz, an appeal was filed noting that former CIA Director Jim Woolsey had previously disclosed the Agency’s interest in bin Mahfouz in Woolsey’s Congressional testimony. It was in this testimony that in 1998, Woolsey reportedly incorrectly accused bin Mahfouz of being the brother-in-law of Osama bin Laden. Woolsey later denied that he had meant to refer to bin Mahfouz, though the L.A. Times notes that “comments Woolsey made during his testimony strongly suggest that he was referring to bin Mahfouz.” In response to the appeal, the Agency upheld their original decision.

As the Agency’s appeal response noted, the appeal was filed in response to “the action(s) of the office of the Information and Privacy Coordinator” - Michael Lavergne. The decision was upheld by the Executive Secretary of the Agency Release Panel - Michael Lavergne.

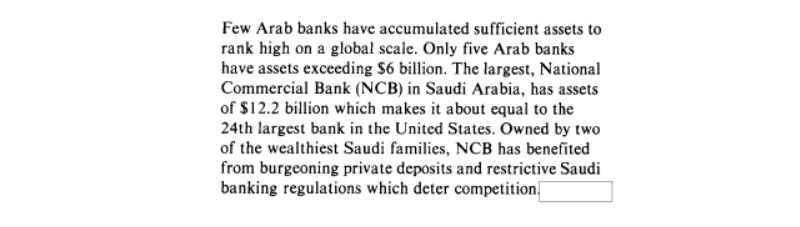

It’s not just this quirk in CIA’s FOIA bureaucracy that truly casts doubt on the Agency’s declaration that they can neither confirm nor deny any information on him (the infamous Glomar response). What truly undermines the blanket Glomar claim is the fact that the CIA had declassified information on bin Mahfouz eight years before, and had already placed the information on the CIA’s declassified database: a CIA research paper from 1982 on Arab Banking.

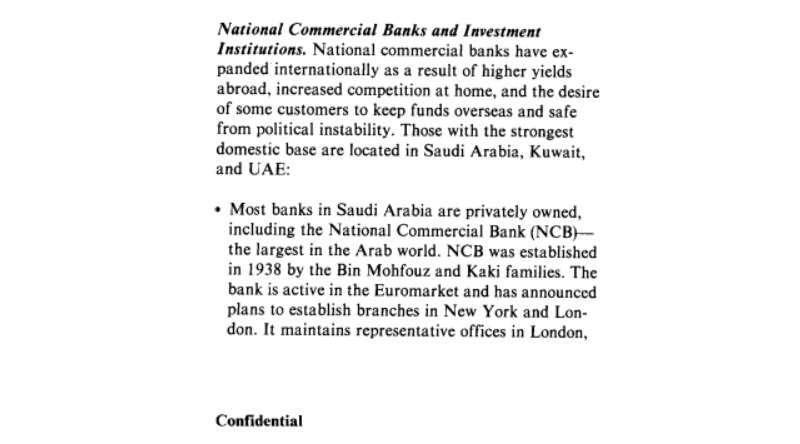

The CIA study noted bin Mahfouz’s bank, the National Commercial Bank, named in the FOIA request, was the largest bank in Saudi Arabia, noting that it was “owned by two of the wealthiest Saudi families.”

Several pages later, the declassified study explicitly identifies the families as the bin Mahfouz and the Kaki families. bin Mahfouz’s personal involvement with the bank had begun seven years earlier, leaving little doubt that he was included in the CIA study.

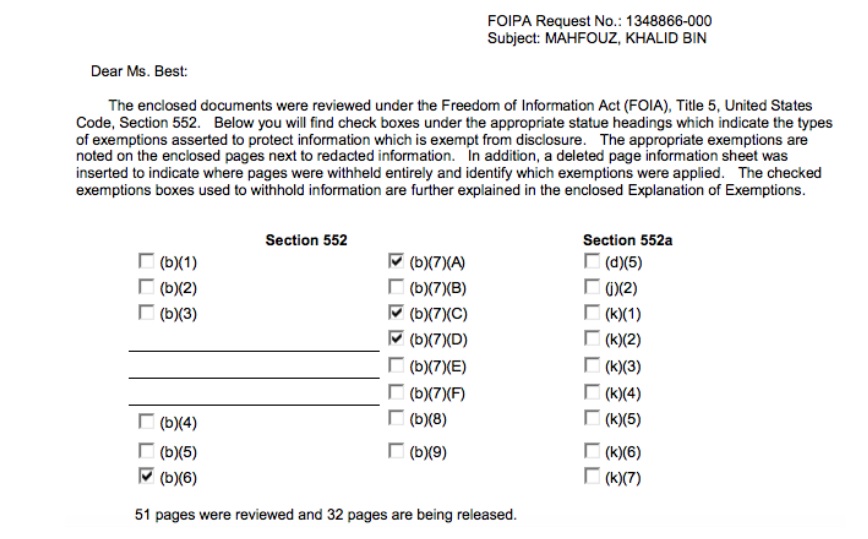

A similar request filed with the FBI produced a few documents, most already public or heavily redacted. The redactions themselves are curious, however, as they repeatedly claim b(7)a in relation to bin Mahfouz himself and the investigation of BCCI.

One heavily redacted 302 form, memorializing an FBI interview, describes some of bin Mahfouz’s business dealings. The FD-302 repeatedly cites b(7)a in the exemptions, meaning that their production “could reasonably be expected to interfere with enforcement proceedings.”

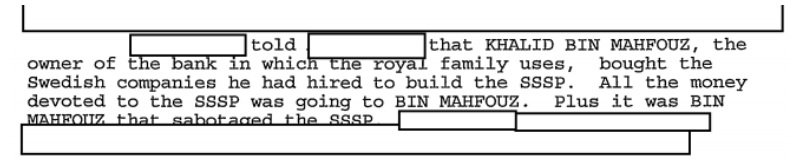

The interview makes a number of statements about bin Mahfouz, which are almost entirely redacted. Only small glimpses remain unredacted. In one section, bin Mahfouz is accused of having “sabotaged the SSSP.”

Another section briefly describes bin Mahfouz’s heart attack and an attempt to sue bin Mahfouz over the SSSP.

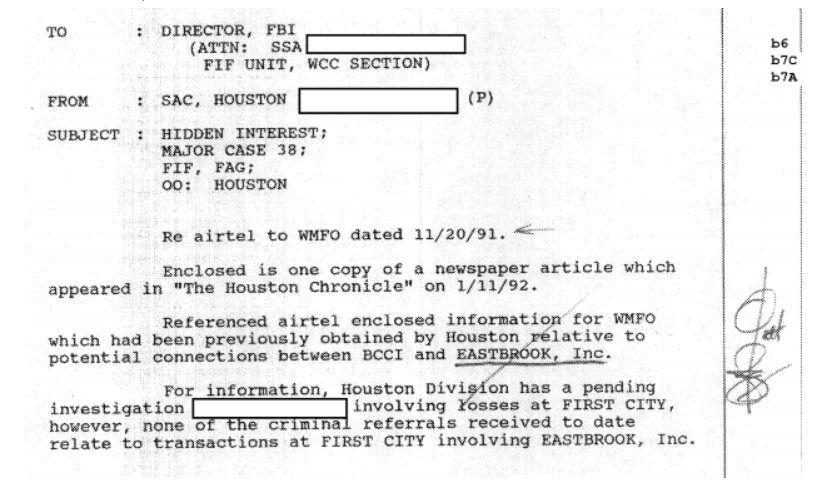

Several portions of the file contain open source materials, such as newspaper clippings. Part of the cover sheet for one of these contains b(7)a redactions. The cover sheet describes part of the BCCI case, with the article itself briefly mentioning bin Mahfouz.

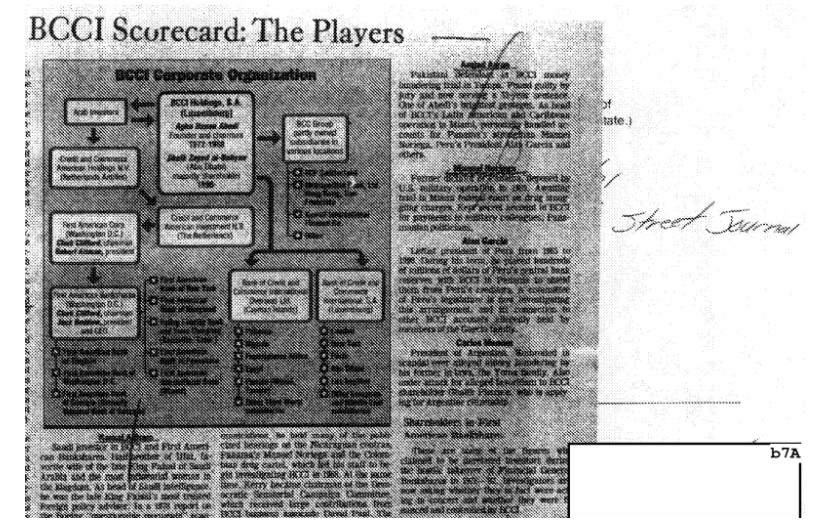

Both the marginalia and cover sheet for a newspaper article describing “the players” in the BCCI case, mentioning bin Mahfouz, remain redacted under b(7)A.

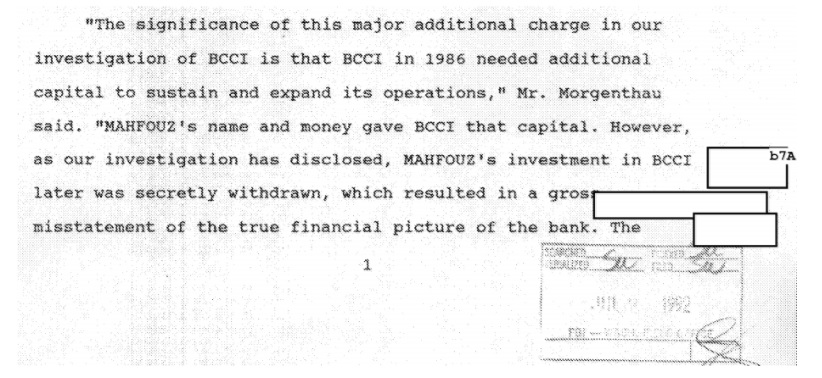

Similarly, marginalia in a 1992 Justice Department press release on BCCI and bin Mahfouz bears the b(7)a exemption marking.

While somewhat surprising, the b(7)a exemption doesn’t appear to be entirely without merit. Even after bin Mahfouz’s death, there were investigations ongoing about others’ ties to his family. While the marginalia redactions and redacted file numbers relating to the BCCI case appear suspect, the case itself may not be entirely closed: efforts to recover money lost to BCCI were ongoing until 2012. An appeal has been filed, challenging the integrity of both the FBI’s search as well as the integrity of the redactions, which seem excessive.

While the appeal may result in more being released, it seems that both the FBI and CIA are determined to keep the case close to their respective chests. You can read a portion of the file below, or the rest on the request page.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via South China Morning Post