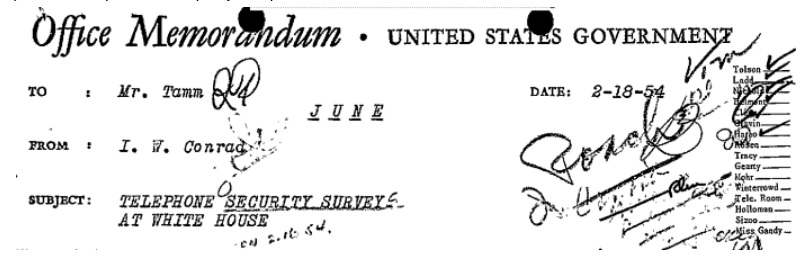

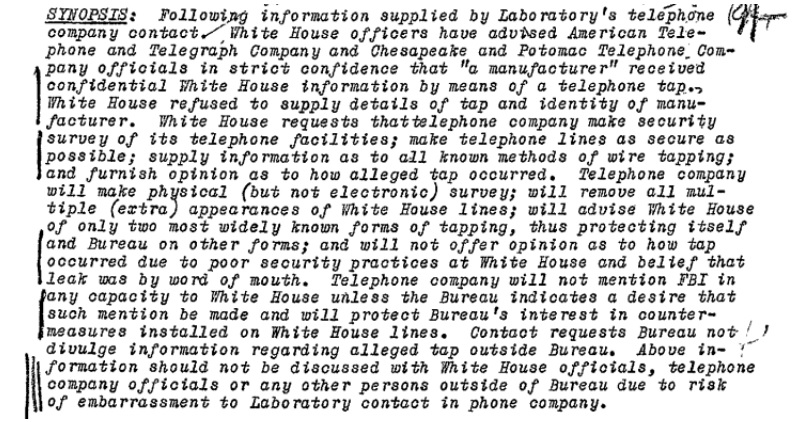

A FOIA release of Federal Bureau of Investigation’s file on Technical Security Surveys, or counter-surveillance measures, includes a “June Mail” entry describing the White House’s 1954 report that their phones had been tapped. According to the file, the FBI and the phone companies shared more information with each other than with the White House - and they wanted to keep it that way in order to protect the phone company’s reputation and the FBI’s methods.

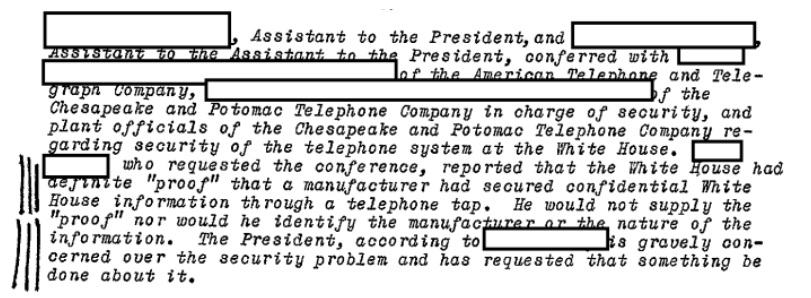

The June Mail designation, used for the FBI’s most sensitive sources and “highly confidential or unusual investigative techniques,” is fitting for a file that describes techniques apparently too sensitive to share with the White House. The White House seemed just as disinterested in communicating with the FBI, whether out of embarrassment, distrust, or simply a misguided idea of who to contact. Rather than contact the FBI, the Assistant to the President (also known as the Chief of Staff) and their assistant had reached out to AT&T and the Potomac Telephone Company on behalf of the President, who then reached out to the Bureau through the FBI Laboratory’s telephone company contact.

Curiously, the FBI decided to redact the name of the Chief of Staff, despite it being readily identifiable as Sherman Adams, and just as readily identifiable that he had died 24 years before the Bureau (improperly) redacted the file, negating the cited privacy exemption. This begs the question of whether the Bureau was just sloppy, or actively acting in bad faith when it made those redactions.

According to the Chief of Staff, they had been informed “in strict confidence that ‘a manufacturer’ had received confidential White House information by means of a telephone tap.” The White House apparently refused to provide any details of the tap, the source of the information or the manufacturer in question. President Dwight Eisenhower was “gravely concerned” about the alleged phone tap and asked his staff to do something about the security problem. As a result, Adams inquired with the phone company about what could be done, and requested information about the process of phone tapping. The phone company, in turn, decided to make a minimal check for taps … and withhold information about the processes of tapping phones in order to protect the Bureau’s methods and the company’s reputation.

At the same time, the company decided on not telling the White House that they decided (before checking) that there was no phone tap.

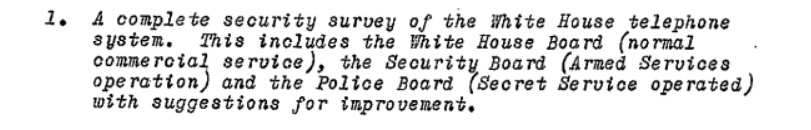

The White House made four specific requests of the phone company. The first was for “a complete security survey of the White House telephone system.”

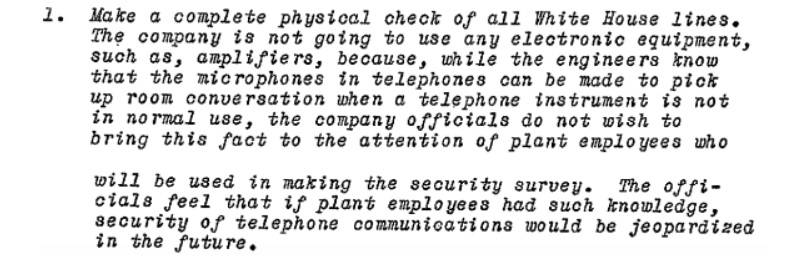

Instead, the phone company decided to make only a physical check of the White House phones, without performing an electronic sweep. The reason for this was to prevent “plant employees” from learning that the microphones in phones could be used “to pick up room conversation when a telephone instrument is not in normal use.” The phone company’s officials felt that this would threaten the security of phone communications.

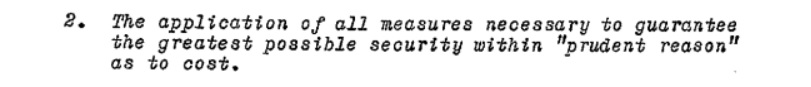

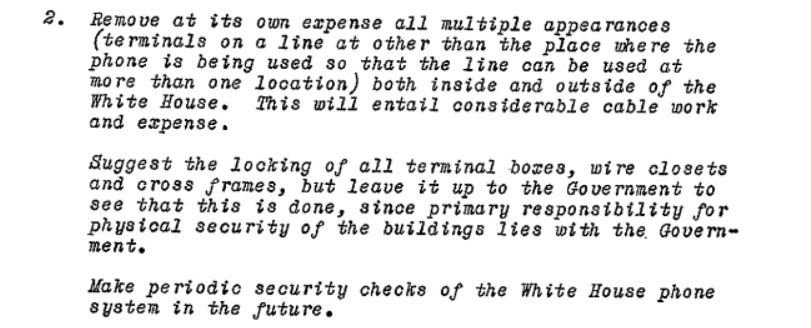

Second, the White House requested that the company take “all measures necessary to guarantee the greatest possible security” within reason.

In response, the phone company decided to remove duplicate phone lines and suggest that the government secure terminal boxes and wire closets on government property. The company would also “make periodic security checks” of White House phones in the future.

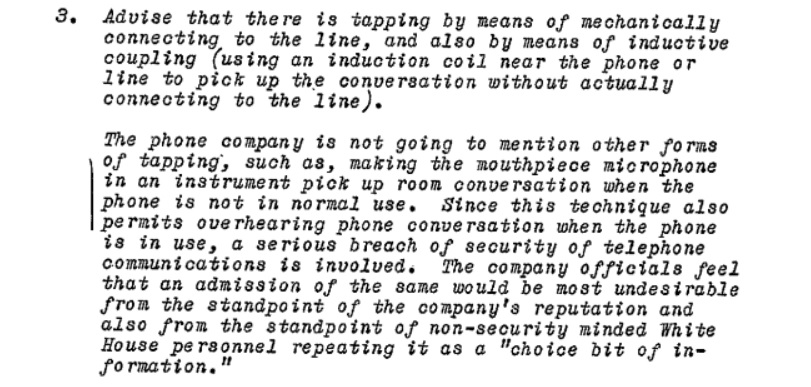

Third, the White House requested information on “all known methods of telephone tapping.”

In response, the phone company decided to only tell the White House about literal, and simple, wiretaps and straightforward induction phone taps. The phone company would withhold, however, information about “a serious breach of security of telephone communications” that allowed phones to be used as listening devices when not in use. According to the phone company’s officials, admitting this was possible might lead to word of it being possible leaking out from the White House. More significantly to “the standpoint of the company’s reputation,” the White House learning of it “would be most undesirable.”

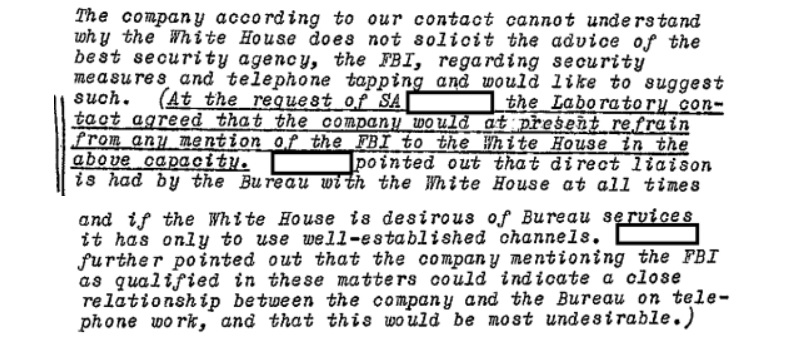

The FBI actively decided not to get involved since the White House hadn’t contacted them. The Bureau also requested that the phone company not mention the FBI to the White House, since that “could indicate a close working relationship between the company and the Bureau” which would similarly be “most undesirable.”

Finally, the White House requested the phone company’s opinion on how the wire tap had allegedly been accomplished.

In response, the phone company would “offer no opinion” as answering the White House’s inquiry “would be presumptuous and tantamount to telling the White House how to conduct its business.” In the company’s opinion, shared with the Bureau but not the White House, the problem was likely that secretaries at the White House monitored phone calls with permission of their superiors, and that this security violation led to a leak by word of mouth.

To protect the surveillance countermeasures the FBI had installed on the White House phones, the Bureau planned to brief the phone company on avoiding removing or exposing the countermeasures. If their existence was revealed, they would be described as “security devices for the White House” without mentioning the FBI’s involvement.

As mentioned above, the phone company had decided before examining the phones or phone lines that there was no tap. Their reasoning was simple: the tap didn’t exist because if it had, the White House would have contacted the Bureau and not the phone companies.

The matter doesn’t appear to have been followed up on by the Bureau, at least not in that section of the large file on the Bureau’s Technical Security Surveys. As a result, we may never know if the White House’s phones really were tapped. Since both the Bureau and the phone company decided not to fully investigate, or to properly educate the White House, it’s likely that neither did the Bureau.

The following year, however, the Bureau did discover that the White House’s phones could be “readily tapped” and that other countries may have had access.

You can read the relevant section of the FBI file below, or the rest of the release on the FBI’s Technical Security Surveys on the request page.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons