A series of declassified Central Intelligence Agency memos describe part of the Agency’s investigation into Jack Anderson (of whom the CIA was never a fan), and his sources and methods (which included unethical practices such as homophobic surveillance, blackmail, and lying about his sources) - specifically his apparent use of hundreds of stolen Agency documents. The memos even call for a Congressional investigation into Anderson and whether or not he was part of “a deliberate disinformation campaign.”

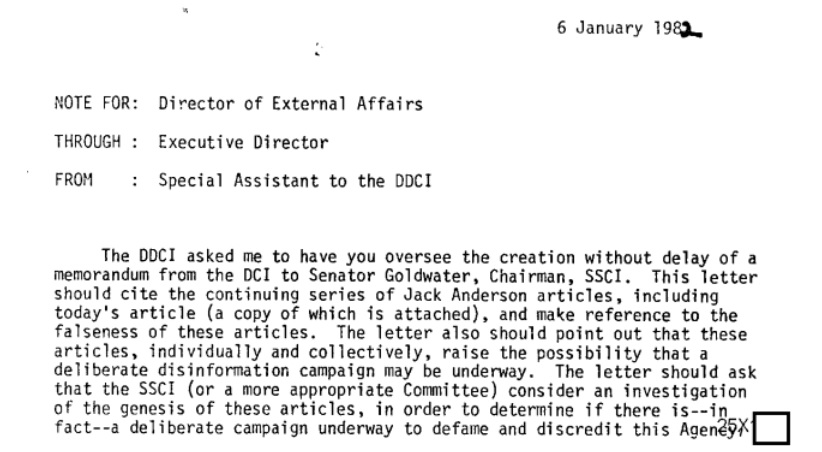

One memo, dated January 6th 1982, directly accuses Anderson’s syndicated articles, dubbed the Washington Merry-Go-Round, of “falseness.” The memo requested that the CIA Director write the Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee to raise the issue. The Agency had apparently detected a pattern in Anderson’s articles that raised “the possibility that a deliberate disinformation campaign may be underway.” The Agency’s Deputy Director, along with the Director of External Affairs and the Executive Director, wanted Congress to look into the origin of the articles, including whether or not Anderson’s articles were part of a campaign “to defame and discredit” the Agency.

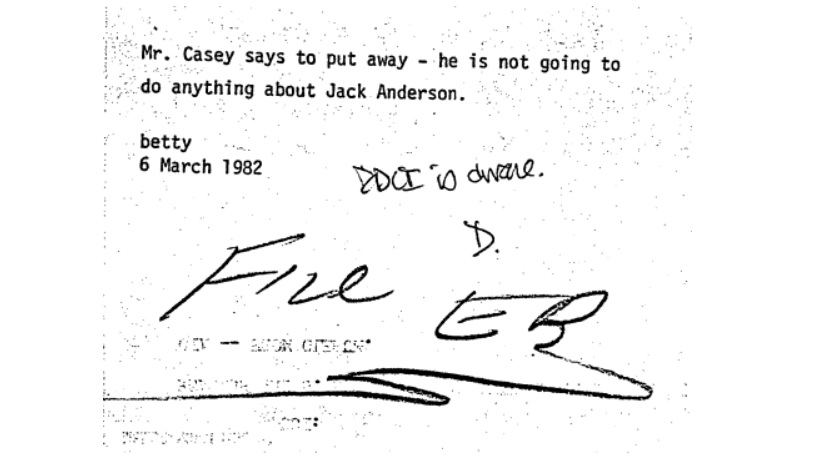

Several months later, it seemed that the issue was dead - the Director was, according to a note, “not going to do anything about Jack Anderson.”

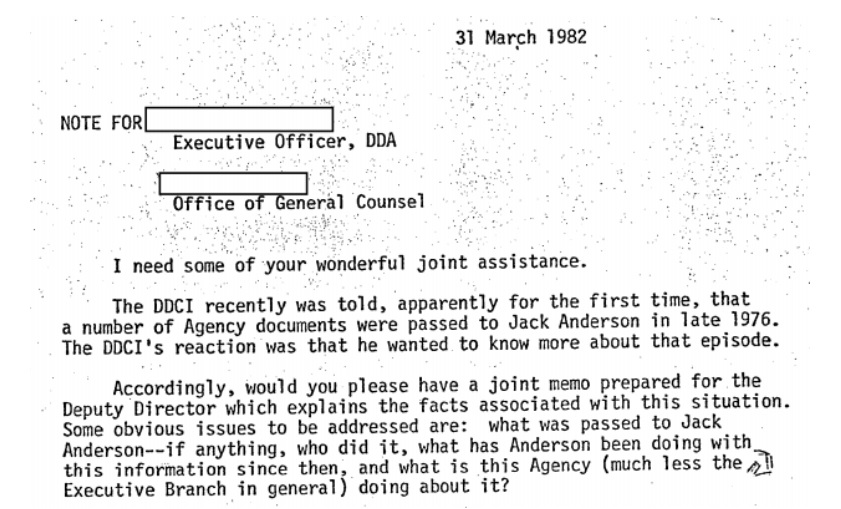

The Anderson issue would be reraised later that month when the Deputy Director learned that Anderson had received a number of Agency documents in 1976. Understandably alarmed by the news of the leak, the Deputy Director requested more information about it and what was being done in response.

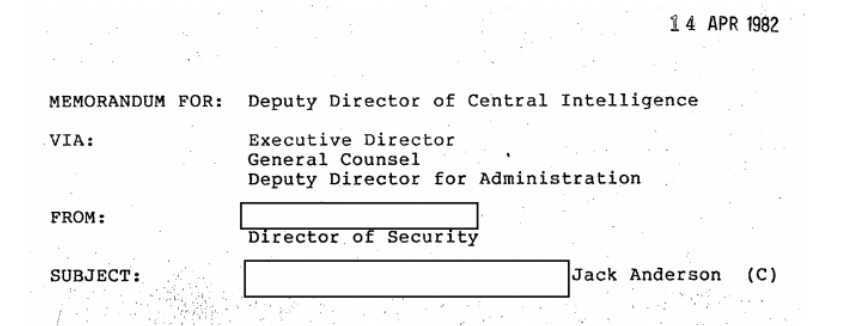

Two weeks later, the Deputy Director received the requested memo, originally classified SECRET, from William Kotapish, the Agency’s Director of Security.

The affair seems to have first come to the attention of the Agency in June 1979, thanks to a retired CIA analyst. The former analyst had been contacted by Dale Van Atta, a reporter working for Anderson. Van Atta showed a briefcase of “highly classified CIA documents” to the analyst in an effort to find out what some of the code words meant and “how valuable they were.” The former analyst reported the encounter to both the CIA and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, along with the copy number on one of the National Intelligence Daily reports, which Anderson and Van Atta (or their source) had failed to remove. The Agency’s Office of Security was able to trace the copy to an National Security Council staffer who’d left the NSC in 1976.

When questioned and polygraphed by the Bureau, the former staffer initially admitted very little while providing what are described as “suspicious responses” to some of the questions. When confronted about these answers, he admitted to taking “an unknown number of classified CIA and Defense Intelligence Agency documents” to his home, ostensibly “in order assist in the preparation of a book.”

The former staffer denied having provided them to Anderson or The Washington Post, hinting that his wife might have responded to “marital difficulties” with a fit of anger that ended in her giving the documents to the Post. When the Bureau attempted to interview her, she refused to take a polygraph exam and said she would retain a lawyer - both wise decisions regardless of her guilt or innocence. One FBI agent working on authorized disclosures believed the FBI had “a very strong case,” but stated that the Justice Department wouldn’t let the Bureau continue the case.

CIA’s Office of Security estimated that Anderson had “approximately 400 classified documents” on the basis of his column in the Post along with his comments on television and the radio. These documents included several hundred NID documents, DIA Summaries and Appraisals, National Intelligence Estimates, National Intelligence Bulletins and many National Security Decision Memoranda from 1969-1976, along with diplomatic cables and reports from the Bureau of Intelligence and Research. Although the Agency believed the documents ranged from 1969-1976, they concluded that the majority of them were from 1975 and 1976.

Anderson’s speedy use of the NIDs led CIA to conclude that he had them indexed by country. The Agency noted that Anderson had used this information to repeatedly lead his readers to believe that he had “a direct line into CIA at the highest levels.”

After the CIA learned that Anderson had copies of the stolen articles, Anthony Lapham (CIA’s then-General Counsel) recommended that DOJ initiate a civil action against Anderson to recover the documents through a Writ of Replevin. The Attorney General declined, with CIA raising the issue again in the spring of 1981. A little less than a year later, after Reagan had taken office, senior DOJ personnel indicated that a Writ of Replevin was the Agency’s best option to recover the materials. CIA’s new General Counsel, Stanley Sporkin, recommended further investigation to trace the chain of custody of the documents and get information about exactly when and how they had gone from the former NSC staffer to Anderson. If the Agency was able to learn this, “then and only then” should CIA begin legal proceedings.

According to the minutes of a Security Committee meeting from January the following year, the Agency was still debating the issue, which was raised while discussing the creation of a database of leaks. Maynard Anderson (no relation) of the Office of the Secretary of Defense noted that the Deputy Under Secretary for Policy, General Richard Stilwell, was still interested in pursuing the matter - as was both CIA and NSA.

While Stilwell “wanted to encourage action” on the Anderson matter, it’s unclear whether or not any was. FOIA requests have been filed with both FBI and CIA to learn more about the stolen documents. While the theft of the NSC documents was itself illegal, Anderson’s acceptance of them was not as there’s no reason to believe that he solicited their illegal removal. A separate FOIA request has been filed with the Agency to learn more about their proposed inquiry into whether or not Anderson was part of a deliberate disinformation campaign. Regardless of their findings on this question, CIA’s pre-existing negative general opinion of Anderson is unlikely to have changed.

You can read the CIA memo on the stolen NSC documents and Anderson’s receipt of them below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons