In early February 1945, a 26-year-old man from Upper Darby, Pennsylvania submitted his application for employment to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Like many of his generation, he had just finished his time in the U.S. Army, first in Hawaii and then in Virginia, where he was a Physical Reconditioning Officer and learned to be a fine marksman. Now he wanted a job with the feds, preferably in a position as a physical education instructor and a starting annual salary of $3500.

At the time, the Bureau could offer him no such position; he could take another job at half his asking price. The young man respectfully declined, and the agency felt no great loss. After all, as his files noted, they weren’t too keen on the cut of his jib anyway.

It would not be the last time Hoover’s agency would hear from him. In the decades to come, his relationship to the Bureau would vacillate between one of mutual respect to skepticism and sycophancy. He would, not so long later, get his job with the men in black, and from there he would soon turn his employment into leverage in the private sector, as he would go on to help create - then lead - one of the largest private security firms in the country, an organization that would branch out into corrections and evolve into today’s biggest global name in private imprisonment, GEO Group.

But, at the end of World War II, this man, clocking in at just under 6-feet tall and 190 pounds, was just known as George R. Wackenhut.

Despite ultimate FBI employment of about four years, Wackenhut’s FBI file is hundreds of pages long, a collection of his applicationd assessments, clippings kept by a Hoover concerned by the use of his Bureau’s name to promote profit, and Wackenhut’s letters to its directors - first Hoover and then each other - offering support and help with each transition and public criticism.

By the time George attempted FBI employment again five years after his first attempt, the observing agent had upgraded his impression of the applicant.

This time, it seems, the well-kept man who had spent the intervening years as Chairman of the Physical Education Department at John Hopkins University looked to be a better match for the Agency.

His neighbors and former employers offered positive reviews during the FBI’s background check, though maybe his wife talked too much - not necessarily more than many other ladies but enough to count her as the talkative sort.

On January 27, 1951, J. Edgar Hoover sent Wackenhut his appointment letter. He would make $5000 a year and join the other agents who, at the time, were working six days a week. He would undergo training at Quantico, Virginia, where he made a good impression, and then he was assigned to Atlanta, Georgia, primarily working on check fraud.

His tenure with the Bureau only lasted until 1954, when he submitted his resignation letter, requesting in the process a signed photograph of Mr. Hoover; the man himself obliged.

After three years, a transfer to Indiana, commendations and censures, Wackenhut would join three others to begin their own private security and investigative firm: Fidelifax.

From the outset, it seems, Hoover’s Bureau was concerned about the possibility of their crossing over into the FBI’s jurisdiction, banking on their federal connections and obstructing their own inquiries into the Communist menace.

Nonetheless, Wackenhut kept up friendly relations with his connections at the Bureau, even as the name - Security Services Corporation - and personnel changed.

In 1961, Wackenhut officially introduced Hoover, by way of letter, to the evolution of the security company: The Wackenhut Corporation.

From its inception, the legality of the private security and investigative force has been under question, which nonetheless did little to prevent it from growing quickly.

Meanwhile, the Bureau remained interested in Wackenhut’s personal life, for record-keeping purposes. A rumor regarding the infidelity of both Wackenhut and his wife found its way into the files.

And though they were never officially substantiated, they come up again and again as reasons to never hire Wackenhut back.

Not that he was necessarily looking to do that at all.

His new venture in the private sector was proving lucrative, gathering accounts from the like of the Governor of Florida himself.

The FBI was instructed not to cooperate with the new organization and its reception in the files is cold.

Agents looking to retrieve FBI databases were summarily denied, as was access to Bureau newsletters or other internal resources.

Such blocks did little to slow the speed with which Wackenhut and his colleagues had ingratiated themselves to the upper echelon of law enforcement in the Sunshine State.

Nor did they deter his lifelong geniality toward the Bureau.

When Wackenhut would read of mainstream criticism of the agency, he would send Hoover a letter, recommitting his support to him and the activities of the Bureau, gestures that may not have been as well-received as he would have hoped.

He encouraged all in his office to pass on the same regards.

And with his characteristic, mechanical courtesy, Hoover responded with his appreciation.

When the mantle of FBI Director was finally passed, Wackenhut was sure to greet each position-holder with any permanence. From Hoover’s successor, L. Patrick Gray....

through Clarence Kelley…

and William Webster.

He eventually was able to even hire Kelley as one of his own.

In 1984, the Wackenhut Corporation created a subsidiary for its private correctional services. After a string of unfortunate publicity covering sketchy security and prison abuses, the name GEO Group was eventually adopted. Most of the rest of the company was sold to or absorbed by another international security firm, G4S.

Today the company that once bore the name of an athletic Army vet-turned-federal-investigator continues to operate for-profit immigration detention centers and correctional facilities in the United States and abroad.

Wackenhut’s FBI application and personnel file is embedded below, and the rest can read on the request page.

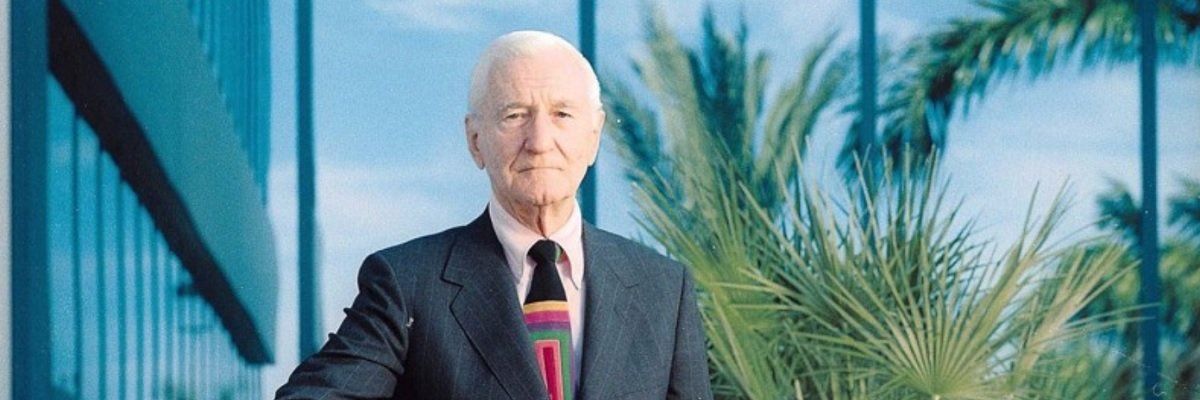

Image via MyPalmBeachPost