Clair George, the CIA officer who was placed in charge of briefing Congress on CIA’s activities, withheld information during his tenure about the beginnings of the Iran-Contra affair, and was later convicted of lying to Congress. George defended his actions by stating he had “been almost megalomaniacal in trying to prove one thing: that we were not involved in that activity because it would have been illegal.” Before he could be sentenced, Clair George was pardoned by President George H.W. Bush, who had in turn misled the public about his own involvement in Iran-Contra as well as his cooperation with the resulting investigations.

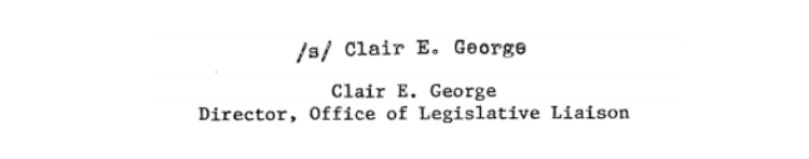

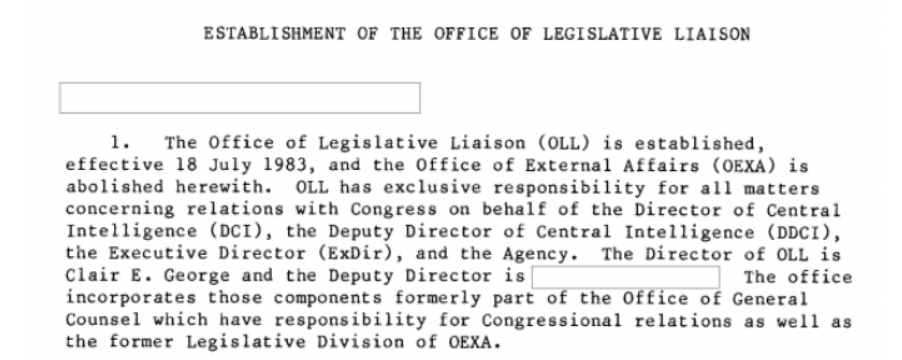

On July 18, 1983 the Office of Legislative Liaison (OLL) was established to replace the Office of External Affairs, with “exclusive responsibility for all matters concerning relations with Congress on behalf of the Agency.” Clair George, who was “a 30-year veteran of the agency’s covert branch,” had been second in command within the Directorate of Operations (DO) before his appointment to head the OLL. He would last less than a year in this position, which George turned into a virtual extension of the Directorate of Operations. According to a CIA draft study cited in CIA’s public study of the Agency’s relationship with Congress, “CIA records reflect that within three months there had been an across-the-board personnel turnover.”

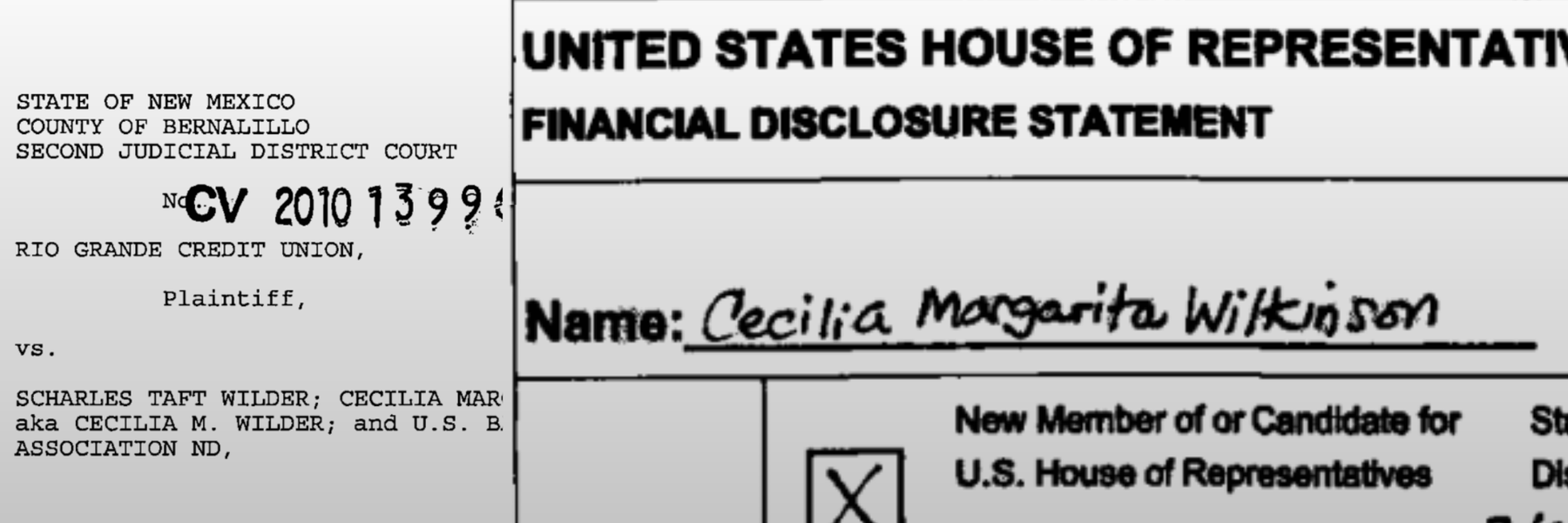

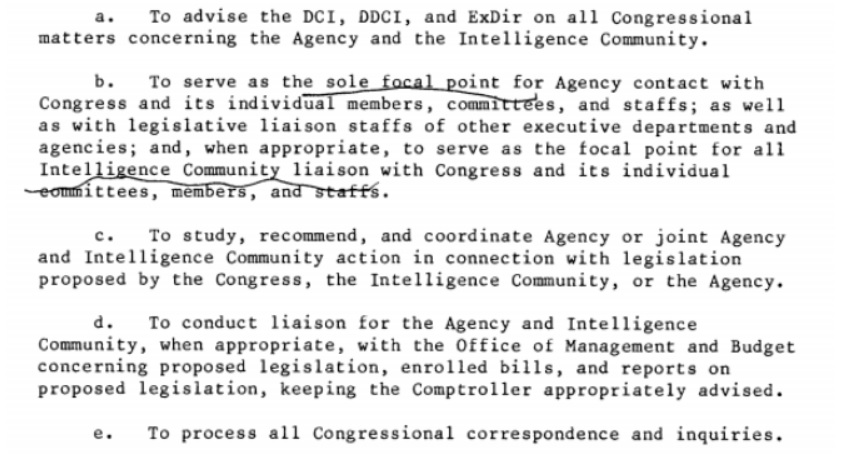

According to the administrative notice sent out at the time of the office’s creation, as Director of the OLL, George’s job was to “serve as the sole focal point for Agency contact with Congress and as the focal point for all Intelligence Community liaison with Congress.” Instead, George denied Congress access to information. Rather than fulfilling the purpose of his duties, the Congressional Committees found him to be “unresponsive and uncooperative.” The Committees concluded that under George’s leadership, they were being ‘gamed by the Directorate of Operations.’

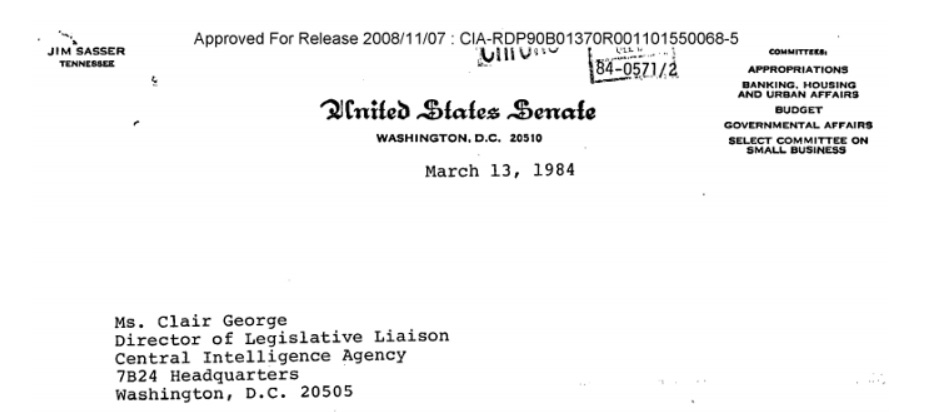

To say that Clair George was unresponsive to Congress’ requests and generally distant from Congress is an understatement. After approximately eight months in his position as the focal point for Agency contacts with Congress, Members of Congress were still uncertain of his gender, having apparently never met with him or spoken with him on the phone.

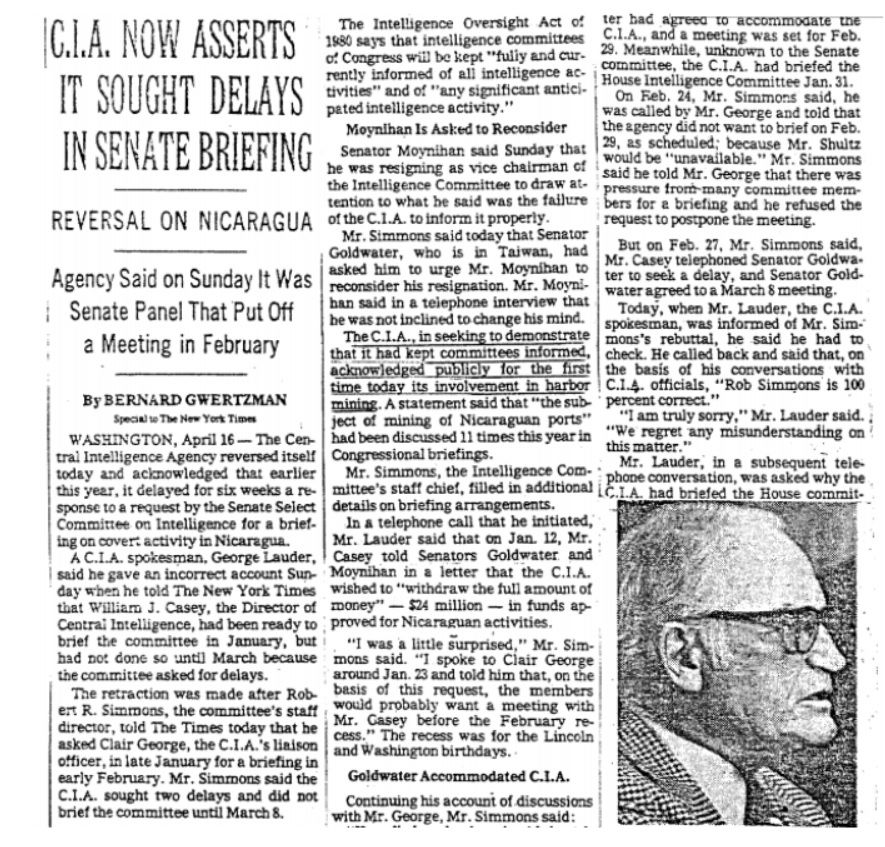

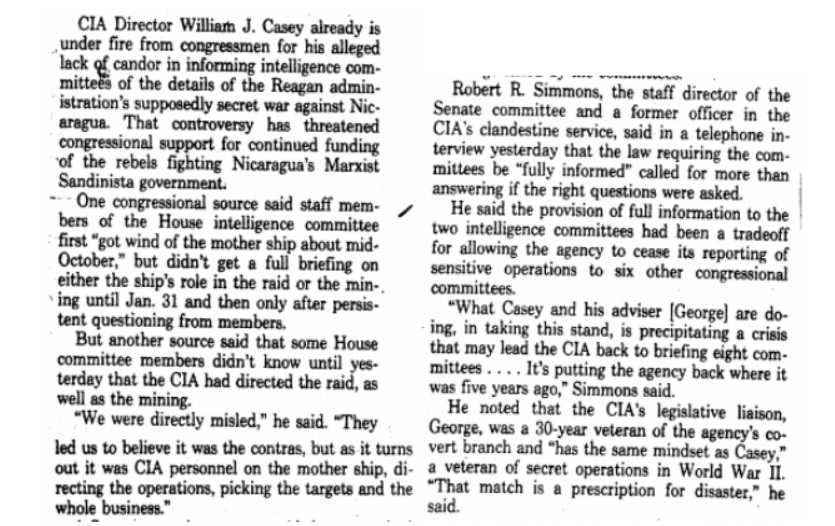

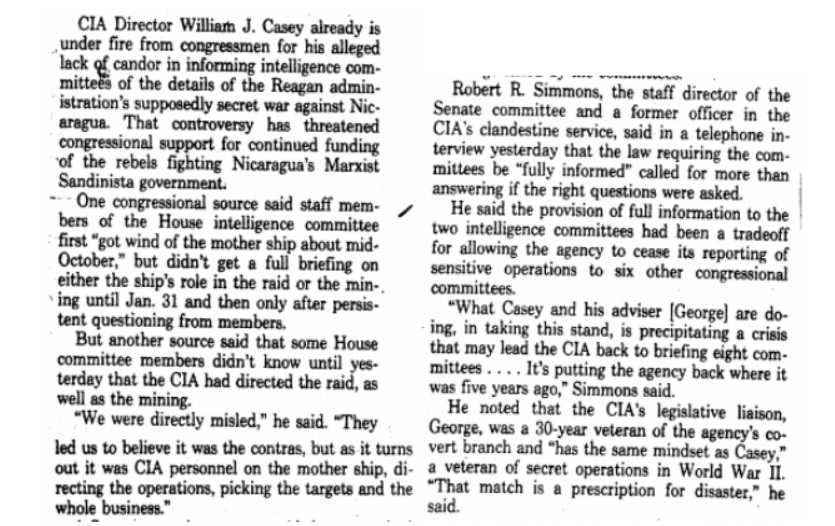

According to a New York Times article in CIA’s archive, the Agency misled the public about George’s failure to brief Congress about aspects of the Agency involvement in 1984’s early stages of Iran-Contra. While Congress was aware of the Agency intention to support Nicaraguan efforts to mine a harbor, considerable information was apparently withheld. Congressional briefings on the subject were delayed twice at CIA’s request. When this first became public, CIA tried to assert that it was Congress that had requested the delays, but when they were caught in the lie, the Agency conceded that it was them, not Congress, that requested repeated delays in the briefings. The briefing requests were directed to George.

As a result, the Congressional Committees stopped speaking to George, and insisted that he be replaced. Congressional staffers complained that they “were directly misled” on issues with “agency officers directly involved” which was “really a high-stakes game.” At a time when the Agency was attempting to further marginalize the GAO by having the two Agency’s oversight committees deny them direct access to CIA records, the Agency’s Congressional liaison was creating a situation that threatened to force them to interface with another half dozen committees. The Agency had had to deal with that until just a few years prior. Robert Simmons, the staff director of the Senate intelligence committee and a former CIA officer, criticized the Agency’s stance and called the presence of George “a prescription for disaster.”

With a few months, George’s time running the OLL would come to an end when he was transferred back to the Directorate of Operations and put in charge of it. While Senator Leahy suggested it was in part a reward for “not telling [Congress] anything.” The Agency denied that it was related to their activities in Central America, insisting it was a “routine rotation.” Senator Moynihan apparently thought it was based “just on the general principle that it is good to do something else.”

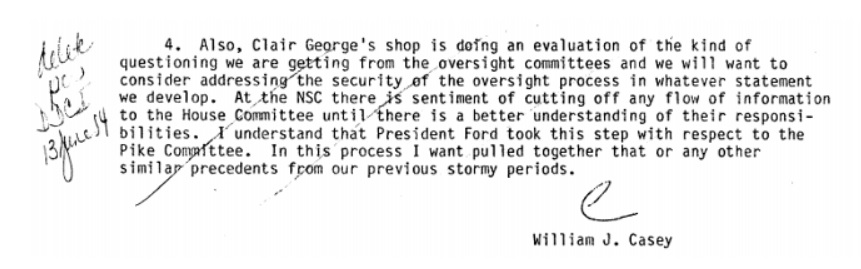

A letter dated June 8th, shortly before George’s transfer from the OLL, and signed by then-CIA Director Casey, states that the NSC was considering shutting off the flow of all information to the House Intelligence Committee. A note in the margins, dated June 13th, from the Deputy Director instructs that paragraph to be deleted. A separate copy of the letter, with the same date and Executive Registry index number, appears to show that the paragraph was “whited out” of certain copies of the letter.

In less than a year as the Director of the OLL, Clair George had effectively killed the Agency’s communications to Congress to such an extent that some apparently went months without ever seeing or hearing from him. He staffed the Office with personnel from the Directorate of Operations, to which he was soon set to return to run, and withheld information from Congress on the Agency’s activities in Nicaragua. When they were caught in this, his office lied about the reason - until they were caught again. In response to intense pressure from Congress, Clair George was finally transferred out of the Liaison office and back to the Directorate of Operations. Once officially returned to his former Directorate, he played a role in the construction and cover-up of the Iran-Contra affair, for which he was convicted of lying to Congress.

Before a sentence could be passed down, then President Bush granted George and others involved in Iran-Contra a pardon on Christmas Eve, stating that the prosecution was simply “criminalization of policy differences.” The pardons, combined with Bush’s refusal to be interviewed, led to the de facto end of the investigations despite the criminal investigation of Bush remaining “regrettably incomplete.”

You can read the memo establishing the OLL embedded below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons