The best sexual assault policies adopted by this country’s law enforcement agencies illustrate a careful balancing act: they are victim-centric, revolving carefully around the physical and psychological needs of the men and women affected, while still meeting the demands of a department trying to prosecute a crime.

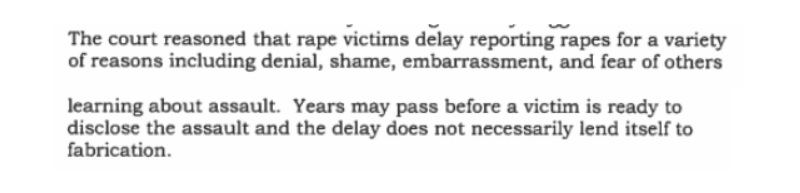

Gardner, Massachusetts manages this feat with their seven-page sexual assault evidence collection and handling policies. The document released to us begin with general guidelines, which includes the important understanding, stemming from a 2005 Mass. Supreme Judicial Court decision, that victims do not always immediately report rape and sexual assault.

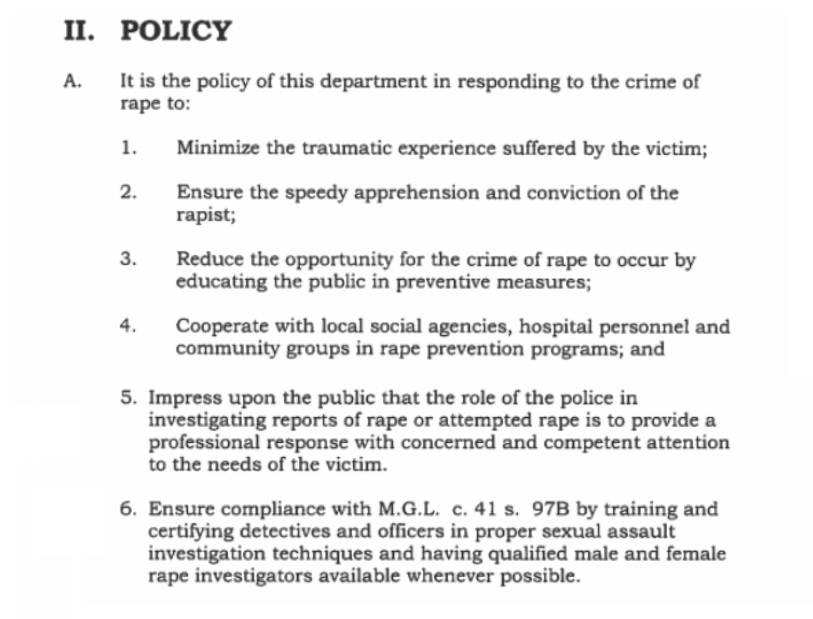

The guidelines then dive into policy, the first bullet point announcing their need to “minimize the traumatic experience suffered by the victim.”

Wording that highlights victim trauma and how to mitigate it is echoed throughout the entirety of Gardner Police Department’s investigation policy guidelines.

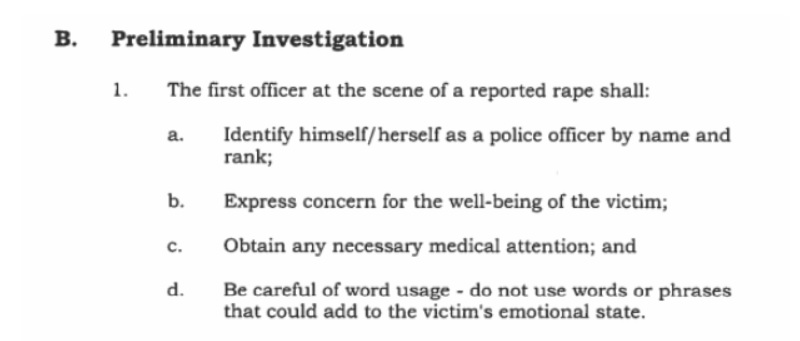

This is seen in their procedures during both the preliminary investigation which instructs officers to “express concern for the well-being of the victim” and not speak to them in a way that will worsen their emotional state …

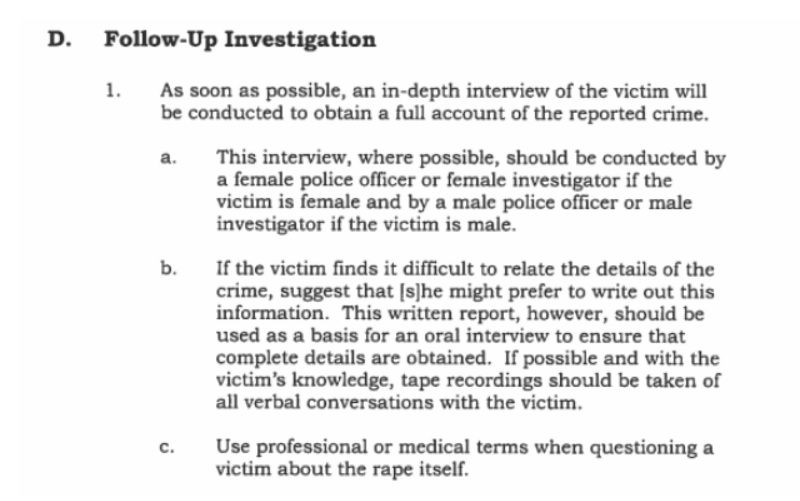

to the follow-up investigation, which includes guidelines clearly written with the victim’s comfort in mind.

Increased sensitivity, however, doesn’t mean the department is lax in adhering to its investigative duties. They clearly enumerate what information must be obtained during an interview and how police are required to receive a written report from the physician so all evidence is admissible in court. Evidence is marked, handled, and stored following specific guidelines. A Rape Reporting Unit exists to “improve the quality or rape investigations and prosecutions,” and certain officers are trained to specifically handle rape and sexual assault cases.

The extensive rape kit backlog exists, in part, because of poor training, a lack of clear policies, and a misunderstanding of sexual assault and survivors of the crime. Gardner’s evidence collection guidelines clearly show a step in the right direction toward combating one of law enforcement’s most troubling and enduring problems.

Furthermore, focusing on the victim’s comfort could lead to the best results for punishing rape and sexual assault, because making the victim feel safe, listened to, and prioritized often results in the best case reports.

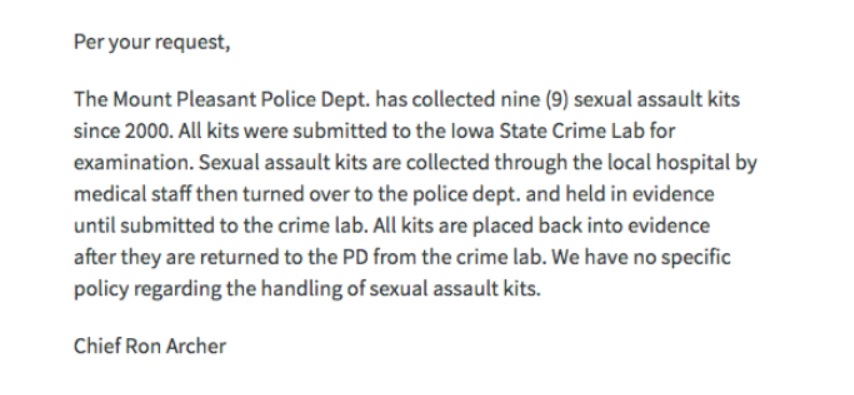

Still, while we can celebrate Gardner for their policies, we must remember this central Massachusetts town is an outlier. Mount Pleasant, Iowa, for example has no written sexual assault evidence policies.

It’s true the town is only home to 8,600 residents, but others like this exist, and when looking at the backlog as a national problem, the chain really is only as strong as its weakest link. As long as towns like Mount Pleasant exist, so, too, will the national backlog. We need to work so cities like Gardner are the norm, not the exception.

Want to get involved? Add your town to our project via the form below, and we’ll submit a request to your local law enforcement.

Image via GirlsSpeak.org