Read Part 1 here

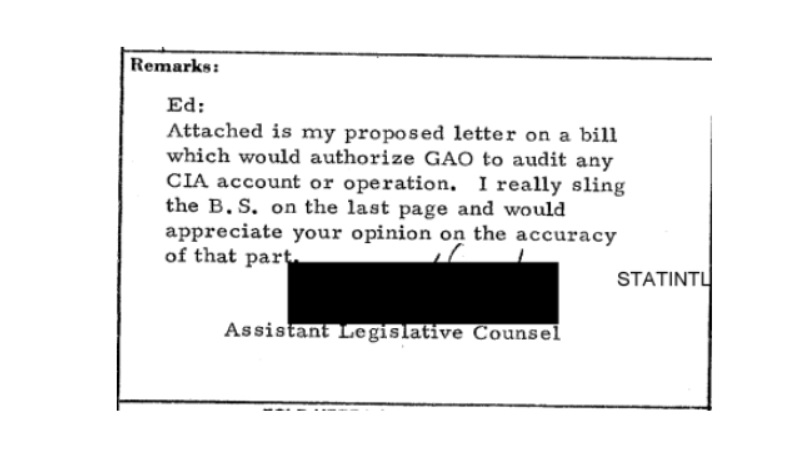

In an April 1975 letter for Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director William Colby, the Agency’s Assistant Legislative Counsel laid out the arguments the Agency intended to make against a bill requiring they allow the Government Accountability Office (GAO) access to CIA records. In an accompanying cover letter, the Agency lawyer drafting the letter noted they “really slung the B.S.,” and asked for Colby’s help in determining if they had overplayed the CIA’s position a bit.

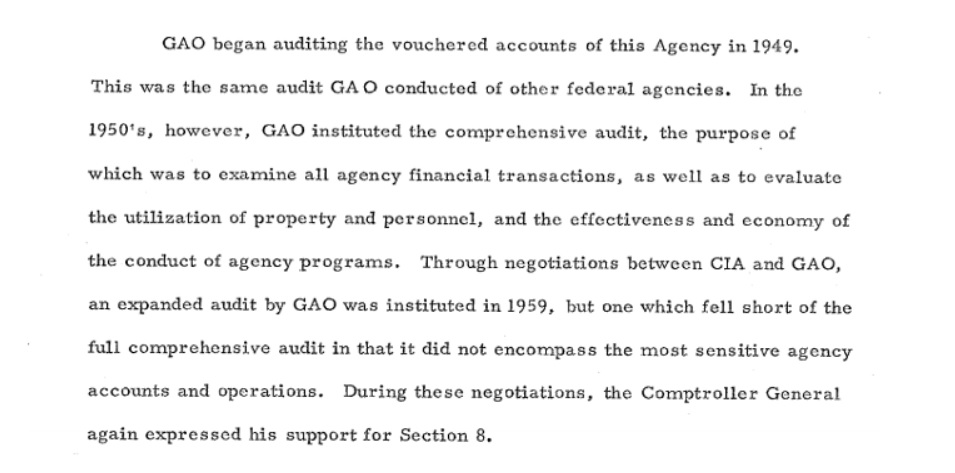

The last page wasn’t the only part of the letter that stretched the truth. According to the letter drafted by CIA’s lawyer, the GAO’s “expanded audit” of CIA only fell short of “the most sensitive agency accounts and operations.” A look at the full record, however, shows that this was far from the truth. Roughly 50% of the Agency’s accounts remained unaudited, including some of the Agency’s overt activities. The record also indicates that the CIA Director at the time had provided the President with inaccurate numbers about how much was subject to audit.

As for the part of the letter where one of CIA’s lawyers saw them “really sling the B.S.”? It was the part where they argued against GAO audits, citing security and legal concerns.

One subsequent revision to the letter suggesting replacing some text to state that the Agency’s internal review process saw the Agency Audit Staff report to the CIA Director through the Inspector General, observing “the same audit principles and standards as the GAO.” The Pike Committee would soon determine, however, “that the foreign intelligence budget was three or four times larger than Congress had been told.”

The revised text also suggested that the CIA Director proclaim that even the previously acceptable GAO audits, which the Agency disingenuously claimed to have supported and wanted, would be disastrous to the Agency. According to this argument, even if the audits were clearly limited in scope, it “could well result in a public impression that all activities were being reviewed by GAO.” If the public gained such an impression, there “would be a serious concern” of “risk of damage to key Agency relationships” which were “essential.”

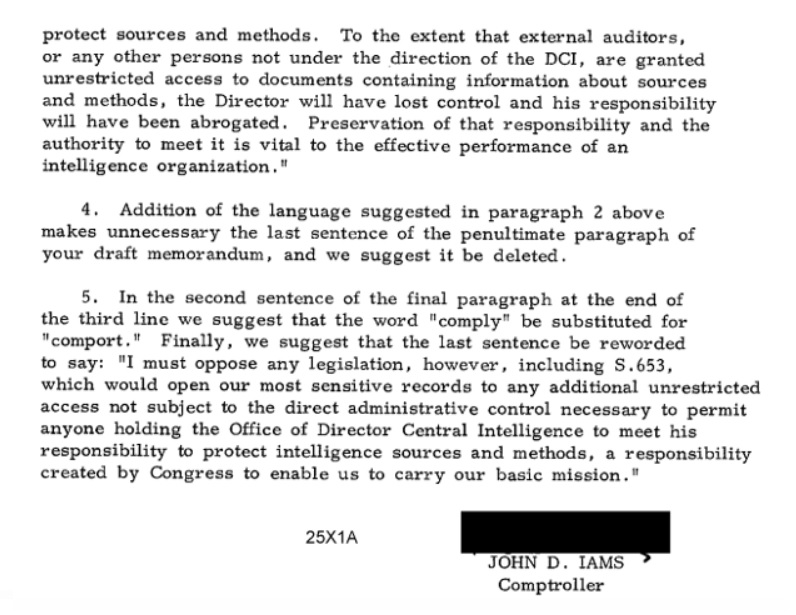

Beyond the Agency’s mercurial “B.S.” arguments against GAO audits, clarity about the true source of the Agency’s objections emerges in the form of a July 1975 letter written by CIA’s Comptroller. This letter makes the Agency’s true concerns explicit, simultaneously identifying the one common thread throughout all of CIA’s objections: control. The Agency simply objected to “non-Agency auditors over whom the Director exercises no administrative authority or direction.” While “GAO auditors can be presumed to be just as loyal and trustworthy as CIA auditors … the DCI exercises no control over them.”

Unless the Director maintained control, and permission to mislead Congress as implied by the Pike Report, the Agency would not be able to meet its requirement to protect its sources and methods, they argued. At this point, it is worth reiterating that CIA falsely claimed they had to withhold letters describing the derailing of GAO audits as one of the sources and methods it now claimed it needed to protect from the GAO audits.

The fact that these arguments were, as CIA’s lawyer described them, “B.S.” is underscored by Congressional testimony submitted by the GAO which made it clear that the issue was not protecting sources and methods. According to the GAO’s written testimony, they had “the most success obtaining access to CIA information when we request threat assessments, and the CIA does not perceive our audits as oversight of its activities.” This is hardly surprising given the fact that, that same year the Agency produced a SECRET memo arguing they should be subject to oversight only when they chose to be.

While Senator Proxmire’s bill was ultimately unable to make any progress, it wasn’t the end of Congress’ efforts to empower GAO auditors. The next part in the series on CIA’s 60 year war with the Government Accountability Office will look more closely at the Pike Committee and the late 1970s. In the meantime, you can read the full letter where CIA’s lawyer really slung the B.S. below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via CIA Flickr